As part of Cappuccino’s ongoing Oscar-nominated movie review series, I’d like to take an in-depth look at the movie TÁR—but in two parts. Part 1 will be spoiler-free, in hopes that those who haven’t yet seen the movie will do so. Part 2 will have spoilers with a special emphasis on the ending of TÁR, which left a lot of people scratching their heads. It is an unsettling and somewhat rushed ending, I’ll grant you, but at a 2 hour and 37 minute run time, writer/director Todd Field likely felt compelled to wrap things up. I get it.

But that doesn’t detract from the gut-punch of this film. Nothing could.

Part 1 (No Spoilers)

TÁR is the ultimate chiaroscuro in that it is two movies: the one you see and the one you don’t. You remember what chiaroscuro is. It’s the use of strong contrasts between light and dark. Caravaggio was a master of it, to cite just one example. What’s omitted in his paintings is every bit as important as what’s visible, and you need to look at both.

And that’s TÁR. What you see in one of the film’s opening scenes is the coolly elegant, supremely erudite Lydia Tár (Cate Blanchett), first conductor at the prestigious Berlin Philharmonic, doing an onstage New Yorker interview with Adam Gopnik (who plays himself). His introduction of her to the audience is a writer’s clever way of introducing her to us, a recitation of her many accomplishments as a world-famous composer-conductor and one of 15 EGOTs (recipients of an Emmy, a Grammy, an Oscar, and a Tony).

It’s a lengthy scene, but an important one because it sets the tone for what to expect from Lydia herself. She’s an undeniably brilliant woman, but instead of trying to connect with her audience, she talks over their heads, spouting a lot of “musicianese” that no one who isn’t in an orchestra pit has any chance of understanding. This is on purpose, a conscious decision on Field’s part to show us who Lydia is: a selfish, driven, egomaniacal genius who strives to always have the upper hand.

“Lydia Tár is many things,” Gopnik says of her, and that creates the framework for the entire movie.

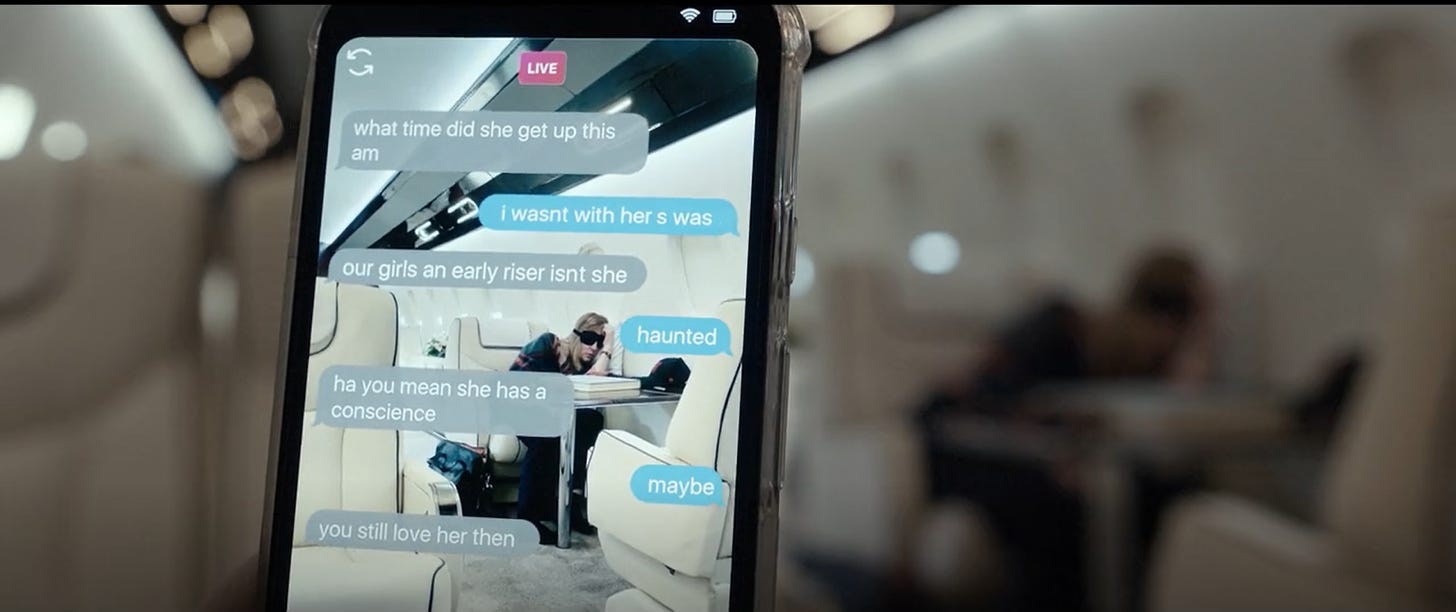

Then there is the “hidden” subplot, which, like a Droste’s Cocoa box, serves as the shadowy movie-within-a-movie element of chiaroscuro. A mysterious red-haired woman sits watching Lydia from the last row. The camera doesn’t linger. We only see the back of her head. But it’s long enough to make us wonder who she is and why we have a vague feeling of unease, especially after a previous scene that gave us this mysterious exchange:

Who these texters are, we never discover, but they actively plot against Lydia. A lesser director than Field might have leaned on the psychological-thriller aspects of this story, but he doesn’t. That would have made her a victim, and she is anything but a victim. His camera remains fixed on Blanchett’s incandescent Lydia, who almost singlehandedly carries the film.

I can’t remember when I’ve seen a more immersive, exhilarating performance. I confess to having cringed through her depiction of Jasmine in Woody Allen’s Blue Jasmine, a movie I thoroughly despised, especially since it was blatant ripoff of Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire—right down to the Blanche Dubois redux. Here, she is allowed to deliver a tour de force without directorial meddling, and extraordinary actor that she is, Blanchett leaves everything, right down to her entrails, on the floor. Love Lydia or hate her, you will never forget Cate Blanchett in this role, which stays with you long after the credits have crept up the screen.

At one point, Lydia takes on cancel culture in the form of a hapless, Gen Z student conductor at Julliard. The film is the intersection of #MeToo and cancel culture, especially when you stop to consider whether it would have been as effective if the Blanchett character were a cis-white male. The answer is no. It had to be a woman. Otherwise, the film’s themes of power and the abuse of power could never have been explored so thoroughly without veering into pastiche.

Still, Lydia isn’t wrong when she castigates the BIPOC pangender Julliard student (played by Zethphan Smith-Gneist) about his dislike of Bach’s music because of his objections to Bach himself, whom he views as misogynistic. “Don’t be so eager to be offended,” she tells him. “If Bach’s talent can be reduced to his gender, birth, country, religion, and so on, then so can yours … The narcissism of small differences leads to the most boring conformity.”

Cancel culture is canceling culture. It’s as true as the idea that those in power—especially in classical music, which is a toxic sausage fest if ever there was one—are overdue for a massive reckoning.

TÁR is about a lot of things, and indeed, power is one of them. In one of the film’s initial trailers, in voiceover, we hear, “Power, true power, requires camouflage. If you want to don this mask, dance this masque, you must sublimate yourself and your identity. You must, in fact, stand in front of the public, and God, and obliterate yourself.”

Imagine then the power of actually being a conductor. “Time is the thing,” Lydia says. “Time is the essential piece of interpretation.”

But perhaps it is not time but the times that are ultimately Lydia’s undoing. Gone are the days when the sexual predations of those in power were given a blind eye. After Lydia’s long-suffering assistant, Francesca (Noémie Merlant) tells her, “I received another weird email from Krista. This one felt especially desperate,” we can already guess that Lydia engaged in inappropriate behavior with her students and underlings. Is Krista the redhead that mysteriously appears outside The Carlyle Hotel?

Francesca then hands Lydia a book that was left for her anonymously—Challenge by 20th century lesbian author Vita Sackville-West. Lydia frantically disposes of it, but not before we see the strange, maze-like diagram hand drawn on the flypaper of the book. It’s something we glimpse again when Lydia’s adopted daughter, Petra (Mila Bogojevic), creates the same pattern, only with clay.

By the time Lydia flies back to her life in Berlin with wife Sharon (superbly acted by Nina Hoss) and little Petra, we see that power is an aphrodisiac Lydia is hardly immune to. She Svengalis young women in a game of seduction. It is, perhaps, the power differential itself that proves irresistible. Then, when things go sour, she abandons her quarry. In Krista’s case, Lydia takes an active role in making sure no one will hire her, which forces Krista to send frantic emails begging Lydia to stop blackballing her within the insular world of classical music.

But time stands still for no one—a point that’s dramatically made when Lydia wakes up to the ominous sound of her own metronome clicking by itself in her study. And a day of reckoning fast approaches. Like many reckonings, this one comes in the form of temptation: a pneumatic young Russian cellist, whom Lydia fixates on immediately.

.

Part 2 (Spoilers)

When a weeping Francesca tells Lydia that Krista (whom she knew; the three of them went on a trip together) has committed suicide, Lydia can barely overcome her own revulsion to give Francesca a hug. Lydia has a lot of revulsion for others since most of her relationships are merely transactional. She’s quick to tell Francesca to delete Krista’s emails, however, and even devises a way to get into Francesca’s computer to see if she’s done it. But it’s already too late. Accusations have been made. Lydia is told to get a lawyer, as Krista’s parents plan to sue. Only now do we see Lydia gazing at an obituary of Krista, whose face is obscured by a headful of shiny red hair.

What kind of person whose former lover has committed suicide keeps poaching after fresh prey? People who feel themselves too powerful to be held accountable for their actions. Unwisely, Lydia denies Francesca (also a former lover) an assistant conductorship, which sends her into a rage. It is Francesca who amends a manuscript of Lydia’s autobiography, Tár on Tár to Rat on Rat. And it is Francesca, we presume, who secretly spearheads the social media campaign to ruin her former mentor.

Lydia’s fall from grace comes swiftly. It is, I believe, director Todd Field’s point. Without a trial or indeed any way to rebut a misleadingly edited video making the rounds on social media, Lydia is fired from the Berlin Philharmonic. The promotion of her autobiography is marred by angry protesters. In these times, an accusation of impropriety is as good as being guilty of it, so when Lydia tries to pick up her child at school, wife Sharon drags little Petra away. The mystery deepens when we see it from a car window, implying that whoever is pulling the strings continues to do so—and is relishing Lydia’s destruction.

In an attempt to rehabilitate Lydia’s image, her handlers advise her to work overseas. We see Lydia struggling to haul her luggage out of an cab in the Philippines, no worshipful young assistants to do her heavy lifting.

And then, in case we feel bad for Lydia, Field reminds us who she is in two separate scenes. In the first, Lydia’s on a boat with a local tour guide who tells her swimming wouldn’t be wise because the water is full of crocodiles. “This far inland?” she asks. When he says the crocodiles escaped during the filming of a Marlon Brando movie, she murmurs, “That was a long ago.” Chillingly, he responds: “They survive.”

Later, Lydia visits a massage parlor, which is actually a brothel, and is told to “go to the fishbowl” to pick a masseuse. A bevy of young women in numbered robes sits in an orchestra-shaped horseshoe. Lydia chooses girl #5—5 also being the Mahler symphony she was never able to conduct.

It’s the last scene that baffles most filmgoers. We watch Lydia ascending the podium of a new orchestra. She dons a headset (this is unthinkable in the classical music world) and three giant screens appear before her. The camera pulls back, and now we see the audience, every member of which is dressed in an elaborate costume. They’re cosplayers for the video game series Monster Hunter.

Oh, how the mighty have fallen.

So, what does director Todd Field want us to make of all this? “It’s always the question that involves the listener,” Lydia tells her Julliard students. “It’s never the answer.”

Field is far too wise to do the work for us. We must decide for ourselves how to interpret the world he has made. My take is this: Lydia is a “rat,” a “monster,” and a “crocodile.” She’s also a brilliant woman. Toward the end of the film, we learn she came into this world as plain Linda Tarr, which implies that Lydia Tár was not born, but created. But by whom? The culture vultures that populate Adam Gopnik’s New Yorker events? By a musical caste system that deifies conductors? Or was it the struggle itself to climb the ranks in a “man’s profession” that turned Lydia into … well, just another man?

Everything in life is about sex, except for sex. Sex is about power. In a hierarchical society, we give inordinate amounts of power to some people and none to others. Then we expect those people not to use it.

It is my belief that power will always be abused, no matter who wields it. And it’s worth noting that in TÁR, the anonymous “nobodies” are the ones who bring down the giant. All abusers leave a trail of human detritus in their wake. In this case, the detritus hits back.

TÁR shows us that yes, the guilty must be held accountable, but people create these monsters. And as long as people exist, monsters can never be destroyed.

Copyright © 2023 Stacey Eskelin

Got some thoughts? Share them with me! The comments section is below.

Beautifully written and observed. The film has stayed with me, and I have wanted to discuss it at length. Your critique of it made me feel as if I have just had a healthy, refreshing conversation about it. Bravissima. Grazie mille. I hope Cate B. receives an Oscar for her performance!

As long as there are people, there will be monsters who abuse power to dominate people. As long as there is power, it will ultimately destroy those who can't control it...and almost none of us are able to truly control it.

I enjoyed Tár, but I think I might have had a better appreciation of and for it if I were a women or, better yet, a lesbian. The political/interpersonal aspects of the movie felt difficult to come to grips with, and I felt ill-equipped to process them as it moved along.

The finale was simultaneously decisive and indecisive, a commentary on how far the mighty and self-absorbed can fall while also not giving the story a feeling of resolution (a particularly American shortcoming- we like things wrapped with a neat, tidy bow).

Nonetheless, I'd pay to watch Cate Blanchett in a condom commercial.