The Fascinating Old-Timey Underworld of Carnies & Freak Shows

Sure, they were drifters and grifters, but who isn't these days?

Few things in life have horrified me and held me spellbound like freak shows and carnivals—or at least their unsavory legacy.

Where I grew up in Pasadena, California, a traveling carnival blew into town once a year, set up shop in a neighborhood park, and then decamped overnight, leaving behind a strangely desolate space where once there’d been lights, carnivals barkers, and a tumbling Ferris Wheel.

By then, the freak show was already a thing of the past, but there was a tent toward the back of the fairgrounds where, for a fifty cent ticket, I could walk past jars with fetal pigs in them, a two-headed snake, blurry photos of yetis. I’d usually have the place to myself, since everyone else seemed to be trying their luck on the midway. A surly teenager with a face full of angry red zits would tear my ticket, and I’d wander around for an hour, nibbling at my cotton candy, trying to distinguish the real from the fake.

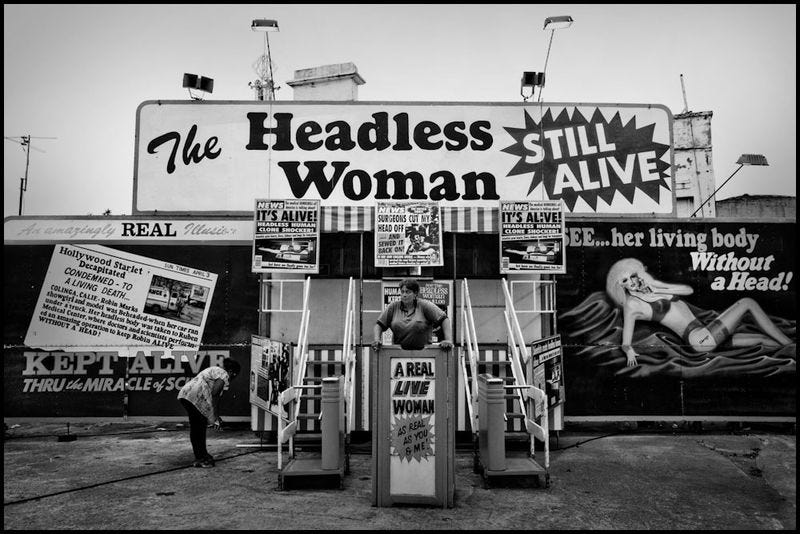

In hindsight, of course, it was all fake. Carnivals are the ultimate illusion, capitalism made flesh. The table is tilted, the board stacked against us, but still we come with our shiny nickel, ready to try again. And the prize? A cheap bunny stuffed with cotton batting, its eyes as flat and dead as playing cards. If that’s not the story of life, what is?

I’ve watched every carny film, from Nightmare Alley (1947, Tyrone Power, Joan Blondell) and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (German horror, 1920) to Carny (1980, Gary Busey, Jodie Foster) and I still can’t get enough. Carny is so awful, by the way, it’s actually worth watching. Foster’s character, Donna, is a bored, small-town, bisexual teenager (you can so tell the screenplay was written by men.) Busey plays a rage-a-holic dunk tank clown whose job is to hurl insults at people from a cage festooned with blinking lights. With diabolical glee, he taunts the locals until they purchase enough grimy baseballs to drop him into the water.

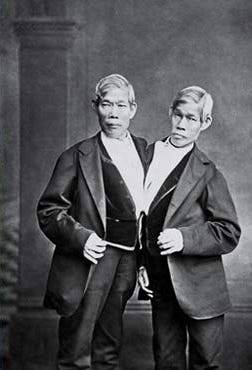

But it was our collective fascination with the physical differences of others that kept us churning through the freak show tents of yore. Traveling carnivals were a theater of extremes, people who offered themselves to our curious gaze. For a little money, we were invited to study Jo Jo the Dog Faced Boy or Hairy Mary from Borneo (who was, as it turned out, not human at all, but a monkey.) One of the most popular attractions was Chang and Eng Bunker, twins conjoined at the sternum, who quit touring in 1839, bought slaves, married sisters, and sired 21 children. The sisters lived in separate houses, so the Siamese twins lived for three days in one house, and then three days in the other.

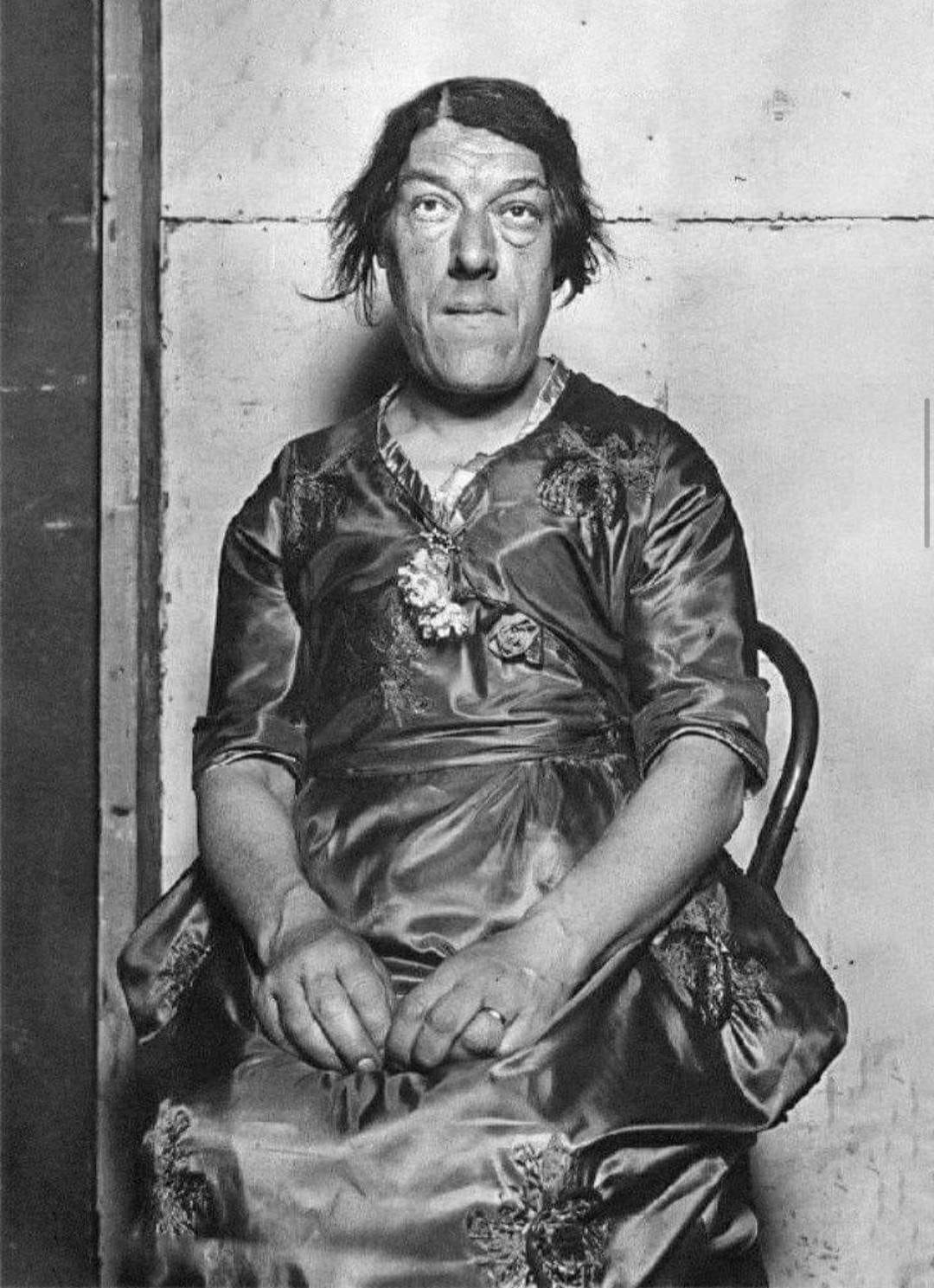

If there is any money to be made, you can be sure Americans (or adoptive Americans) to go all in. Mary Ann Bevan, billed as the Ugliest Woman in the World, was a star in Coney Island’s Dreamland sideshow. She also did guest spots for Ringling Brothers’ Circus. At the age of 32, she started exhibiting symptoms of acromegaly, a growth hormone disorder, which grotesquely distorted her appearance. So, with her husband dead and four children to support, she decided to enter an “Ugliest Woman” contest and won.

As horrified as I am to consider her experiences in that hot, crowded tent, a part of me admires her intestinal fortitude. Nature dealt her a hand of cards, and she played them. But did being gawked at night after night make her bitter? Was her indifference to the staring and rude comments genuine or cultivated? I hate to think of her looking into the crowd, seeing the face of a beautiful woman, and feeling a pang of deep envy. We all yearn to be loved. How could Mary Ann Bevan been any different?

Then came P.T. Barnum and his “pernicious humbuggery.” With Barnum, freak shows became an illusion of an illusion. In addition to the Feejee Mermaid, “an object composed of the torso and head of a juvenile monkey sewn to the back half of a fish,” Barnum started touring with Charles Stratton, a little person billed as General Tom Thumb. Although Stratton was only four at the time, Barnum lied and said he was eleven, which still didn’t absolve him of the sin of teaching the child to drink wine and smoke cigars for the public’s amusement.

Still, as an opponent of slavery, Barnum found himself on the right side of history. When he died at the age of 80 in 1891, he asked the Evening Sun to print his obituary in the hours immediately prior to his death so he could read it.

People are rarely wholly good or wholly evil. Barnum may have exploited “freaks,” but to him, they were both willing and compensated. Slaves were not. At least he got that distinction, which is more than you can say for a lot of people in the 19th century.

Would I have been able to attend a freak show like the ones P.T. Barnum exhibited? Not likely. Maybe I spent too much of my youth being stared at to feel comfortable staring at somebody else. But I will always be fascinated by the skeevy allure of a midway glittering at the end of a dark road. A Ferris Wheel glowing against a night sky. The enticements of the carnies to play their weighted games of chance. The smell of funnel cakes and motor oil and the whole Potemkin Village vibe that even a modern day traveling carnival has.

Carnivals are a lie, of course, an illusion. Yet we’re drawn to them like lemmings. I can’t help but see the zero-sum metaphor about life here. We show up for the shiny lights, participate in the fiction that we’re actually going to win something, and then walk away empty handed.

Oh, and by the way, friend. Can I interest you in seeing a two-headed snake?

Carnivals and freak shows. Love them or hate them? I want to hear your thoughts on the matter, so feel free to leave your comments below.

Copyright © 2022 Stacey Eskelin

Crazy small world. My husband’s ex-In-laws, Robert and Phoebe Kaylor, directed and wrote Carny. It was the only film Robert Kaylor directed (no big surprise why).

Delightful. Your subject matters are always interesting.