MEREDITH FRAMPTON: The Most Sublime Artist You've Never Heard Of

He toiled in obscurity, and and then stopped painting for three-and-a-half decades ... before this happened.

I’m furious with the United Kingdom right now.

Furious.

During last night’s World Championship, I was loudly and vitriolically rooting for Italy. How could I not? Italy is my adoptive land; England is my ancestral one. But England chose to leave the European Union and now owes fifty billion—that’s BILLION—to the EU in legal fees. There’s also the Irish border issue that continues to rear its ugly head, no matter how many times Prime Minister Boris Johnson tries to shrug it off.

So, maybe not angry with the United Kingdom as much as I am its feckless leader.

None of that dims my enthusiasm for the work of English painter Meredith Frampton.

For most of his life—until the age of eighty-eight, in fact—Frampton created one breathtaking masterpiece after another. When his eyesight grew too poor for him to continue painting in his signature smooth, flawless style, he stopped painting altogether. Instead, he studied clockworks and cobbled together bases for lamps. By his own admission, Frampton thought he was would die and be completely forgotten by posterity.

But Frampton was not without his champions. One of them was a curator at the Tate Gallery in London, Richard Morphet, who had long agitated for a new retrospective of Frampton’s work. The trouble was, Frampton was a singular genius whose intense, outwardly calm but preternaturally disturbing paintings never fit in with any of the Tate’s artistic narratives. 1982 was the last time the Tate had shown any of his work, an egregious oversight Morphet had every intention of remedying.

How could a genius of Frampton’s caliber go unheralded for so long?

For all intents and purposes, Meredith Frampton was an ordinary man born of extraordinary parents. His father, Sir George Frampton, was a successful sculptor. His mother, Lady Christabel, was also a painter. During Meredith Frampton’s tour of service during World War One, he was tasked to study aerial photos of enemy territory and draw meticulously detailed maps.

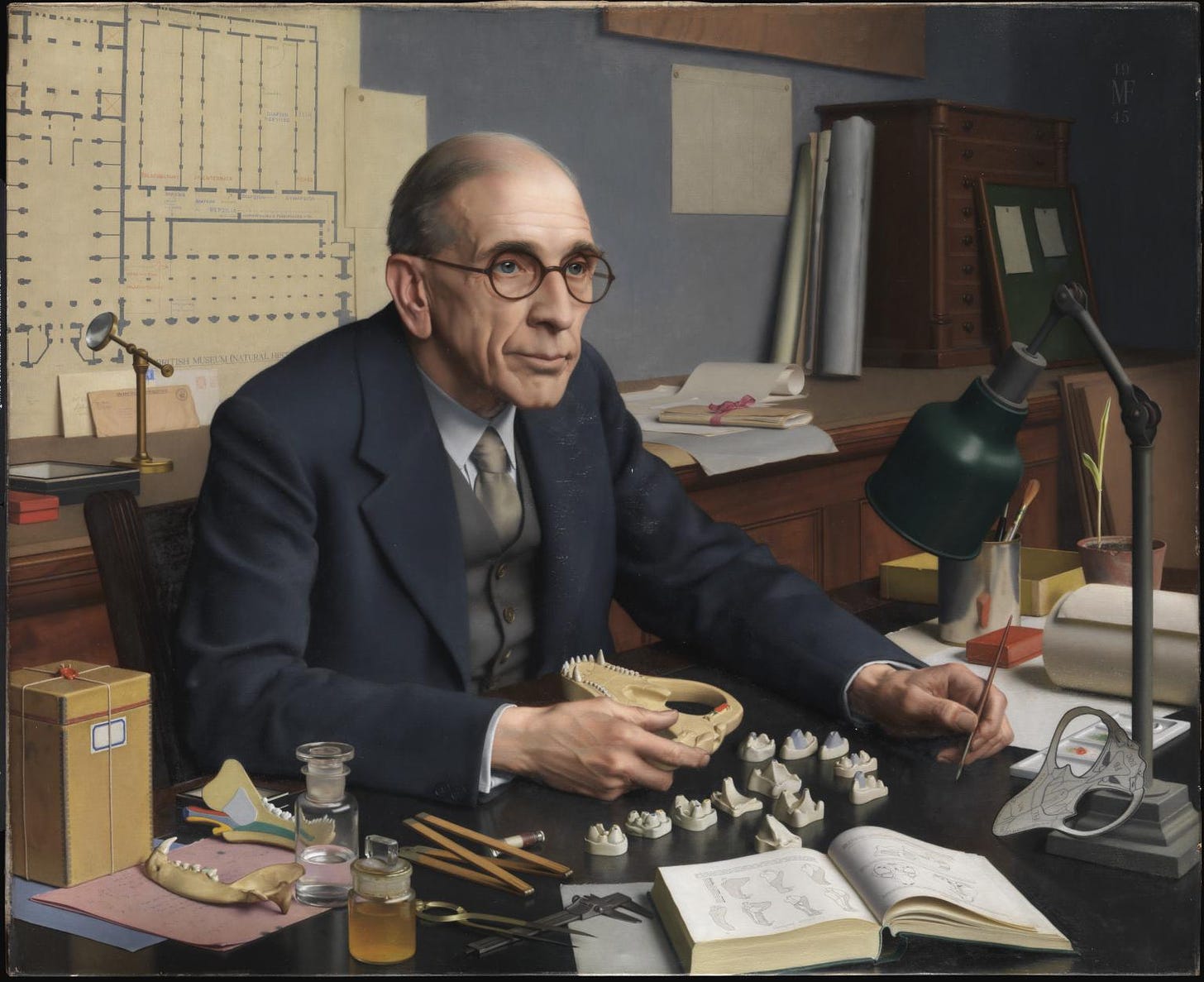

“Precision of observation was absolutely crucial for him,” his champion, Richard Morphet said of Frampton in this BBC article. “And you will notice that, throughout his mature work, maps and schematic diagrams of various kinds keep reappearing.”

To me, there is something quintessentially icy and British about Frampton’s work. It’s the austerity, perhaps, the careful control. He would often work on a painting for an entire year, which explains the poreless skin of his subjects, the flawless polish and, yes, the unsettling undertone of restrained savagery. No human is that smooth. No human is that calm. That Frampton’s portraits are so determined to show you one side of a subject automatically suggests there is another, darker side that wants to remain hidden.

He died in 1984, two years after his last Tate exhibition. And I cannot help but reflect that had Frampton not been born into money, he surely would have had to follow artistic trends just to keep afloat. What a loss it would have been to England and to the world at large had he been anything less than what he was: not a Surrealist, not an Abstractionist, and certainly not Edwardian, but a zeitgeist unto himself: a Frampton.

Do you have a favorite artist? If so I’d love to hear all about it. Leave your comments below.

In many respects the opposite of Frampton (who, indeed, I'd never heard of) I'd have to say my friend Vicki Walsh. It is not stylish these days to work on portraits these days, but that is her almost singular focus. But her portraits are not "smooth"; they are explosive with a kind of flawed energy that is itself almost inhuman: http://www.vickiwalsh.com/index.html

Then I'd have to go with Peter Paul Reubens for the stunning and mythic drama and color.

Hovering in the back of my mind like an itch I can't scratch ...

Frampton's fascination with hands keeps bringing me back Whedon's fascination with feet. Whedon even talks about this in his numerous director's commentaries. But in Firefly, he constantly turns the camera to look at Summer Glau's (who started out as a dancer) feet as she is walking.