How The Hyper-Inflated Housing Market Is Turning America Into A Nation of Rent-Slaves

To call it New Feudalism is to understate the problem.

Over 48,000 Americans live on city sidewalks in Los Angeles, homeless encampments that span roughly 60 blocks—literally, miles—of tents and cardboard boxes. Using words like “fire hazard” instead of “humanitarian crisis,” city officials eject these people during periodic sweeps where, like dust unsettled but not discarded, they wait until the authorities look the other way so they can reclaim their small, ramshackle kingdoms.

One fenced-in parking lot near the 101 freeway in East Hollywood is an actual city-sponsored campsite with 12-by-12 foot spots painted on the asphalt to demarcate “territories.” A row of port-a-potties comes as a welcome alternative to defecating in the street. This city program also provides showers, food, and most coveted of all, 24-hour security.

Being homeless is a dangerous thing in 21st century America. A recent UCLA report estimated that 1,500 unhoused people died while living on the streets from March 2020 to July 2021.

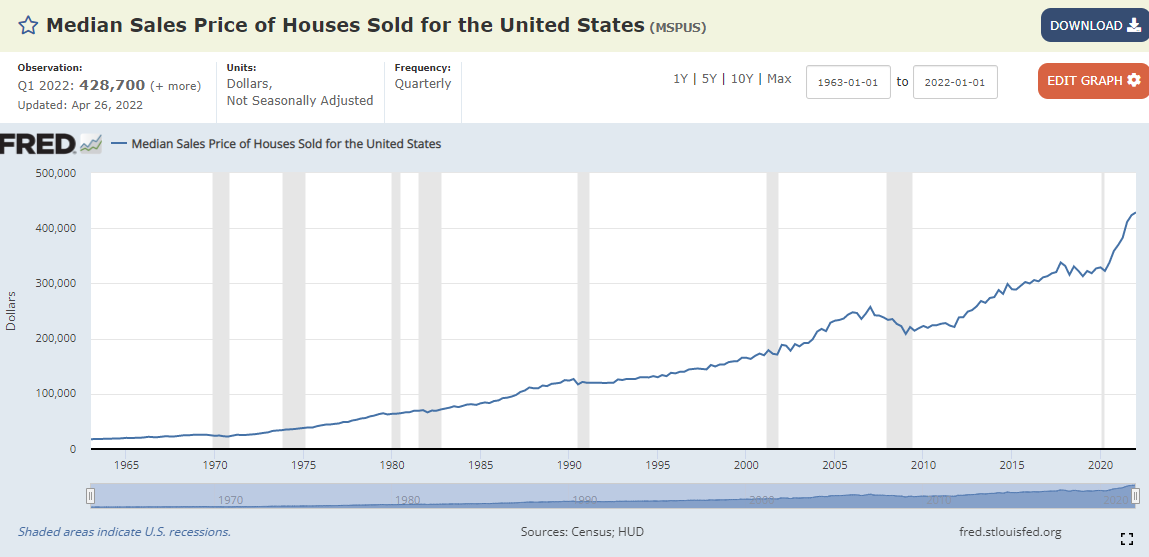

This is a crisis driven, at least in part, by cataclysmically rising rent. Across the nation, rents rose a record 11.3 percent in 2021 and continue to escalate, often in double-digit jumps. Younger Americans are particularly feeling the heat. Pandemic-related material shortages have contributed to construction delays in new homes and rentals, but it is also rising interest rates that are dashing the dreams of would-be homeowners, forcing them to remain perpetual renters.

The problem is, renting is actually more expensive than many fixed-rate mortgages. As of December, 2021, the average listed rent in the U.S. was $1,877 per month, according to Redfin, a Seattle-based real estate brokerage. Austin, Texas, saw the biggest increase last year, with average rent increasing 40% compared to 2020. Redfin economist Daryl Fairweather called the surge "mind-boggling.”

Many experts believe the housing crisis started well before the pandemic drove remote-working parents and their homeschooled children into houses with more space. Today’s housing shortage has its taproot firmly in the soil of the bank-default foreclosure crisis of 2008-2009, when property values plummeted and new construction ground to a halt. When the market finally got rolling again, property developers saw no point in building houses for low-income or first-time homebuyers, which is why today, nearly all new homes are built for well-upholstered, high-end homebuyers. The National Association of Home Builders found that of all the new single-family homes built last year, none—not one—was priced below $100,000, and only 1% were between $100,00 to $150,00. According to one estimate, we have a shortage of 4 million homes in the U.S.

Another piece of the puzzle can be found in exclusionary zoning laws meant to keep white neighborhoods white and Black neighborhoods separate and poor. Single-family zoning, for instance, makes it illegal to build anything (like an apartment, say) that isn’t intended for a single family. This type of zoning is prevalent throughout the nation and traps Black families into low-income neighborhoods by pricing them out of richer ones. Here in America, we have a long, storied tradition of segregation, even if we don’t call it that. Anyone who claims that America doesn’t have a caste system isn’t paying attention.

Now, there isn’t a single state, metro area, or county in the United States where a typical minimum-wage worker can afford even a two-bedroom rental, according to a recent study by the National Low Income Housing Coalition. And traditionally expensive metropolitan areas, such as New York City, San Francisco, Washington, D.C., Seattle, despite the mid-pandemic exodus of tech workers, are spiking dramatically upward again.

According to apartlist.com, as of six days ago:

The average rent for a New York City studio apartment is $3,638

The average rent for a New York 1-bedroom apartment is $4,761

The average rent for a New York 2-bedroom apartment is $6,188

The average rent for a New York 3-bedroom apartment is $6,544

In the words of a very smart friend of mine, Manhattan is no longer a city; it’s an investment portfolio. When poor and middle-income artists—the ones who actually make an area exciting—can’t afford a place to live, it’s the city itself that suffers. Manhattan is still riding on the coattails of Jean-Michel Basquiat and the Neo-Expressionists, a movement made possible by the oh-so-affordable rents of the 1970s and ‘80s. What noteworthy artistic movements have existed in New York City since? Like everything else in Gotham these days, art isn’t about expressing thoughts, feelings, and ideas, it’s about money, stupendous amounts of money, much of it laundered.

The only glut in New York City real estate inventory, apparently, is among units valued between $10 and $30 million. So-called Billionaires’ Row, an exclusive Midtown area of luxury penthouses across seven buildings where apartments have sold for more than $100 million, sits empty and dark. Wealthy foreigners use shell companies to buy these units as a way to shield their names, launder their money, and keep that money safe using a stable currency. This slew of international buyers means the big fancy apartments often remain empty.

Monstrous shadows cast by these buildings fall across Central Park, obstructing the very sunshine city residents go there to enjoy. How ironic that owners are rarely there to enjoy the magnificent views. It would seem that Manhattanites must once again pay the bill for wealthy foreigners who keep driving up the price of real estate. But when a city is almost wholly owned by property developers, here is the result.

In other parts of the country, the housing crisis is just as alarming. The median sales price for existing homes in May was $350,300, up 23.6% from a year earlier, and the 111th consecutive month of year-over-year increases. Unlike 2008-2009, excessive leverage, looser underwriting standards, and financial speculation aren’t responsible for the crisis, which is good. But for Americans themselves, home buyers in the bottom one-fourth of the market have been squeezed out entirely. Conventional wisdom says that Baby Boomers are supposed to be trading in their oversized houses for smaller, more manageable places, but so far, that hasn’t happened—there are no houses to move into. Younger families who might have been able to afford these older, less-expensive homes are out of luck.

Knowing what you do about human nature, what do you think is going to happen to a generation of young people drowning in student loan debt, overwhelmed by the impending climate catastrophe, unable to find jobs in their fields, forced to earn a living as baristas and gig workers without health insurance, and now stuck paying $1,877 in rent, month after month, with zero hope for the future?

There’s no way this doesn’t end bloody. And those younger generations have every right to point the finger at us.

Why?

We’re the ones who let this happen.

To read more about our nation’s housing crisis, click here.

What are your thoughts? Let’s hear ‘em. Be sure to leave your comments.

Copyright © 2022 Stacey Eskelin

One of the problems right now is that, unlike 2004 -- 2007, we are NOT in a housing bubble. Unlike stock bubbles which can be tricky to identify, housing bubbles are relatively tame beasts, easily identifiable by the disconnect between mortgage and rental prices. No such disconnect exists right now, which makes it unclear how the market could undergo anything like a "natural" "correction." (Those words deserved to be individually scare-quoted.)

Much as a despise where I am living, I'd be hard pressed to do better given my finances. Johnston City is the place where dreams go to die, which is why is so affordable. I suppose I can still brag about location for the 2024 eclipse.

A few months before Erin and I got married in 2015, we bought a home in north Portland for $442,000. Yeah, it was a bit above our budget, but it's a great house, we love it, and we're planning on being here for awhile. We weren't thinking of it as an investment, but rather as a home. It's literally our dream home.

Well, fast forward seven-plus years, and our home's value is now estimated at about $740,000. Within 18-24 months, it may well be worth double what we paid for it. It's not as if we've done anything crazy to it, either. We just happened to be fortunate enough to buy at the right time, though that absolutely wasn't part of our thought process.

Our situation is the product of some great good fortune, but what if we were just getting out of college and looking to buy our first home together? There's no way we'd be able to afford to live in Portland. Our good fortune is the flip side of someone else's financial dilemma, and it's hard not to feel a bit guilty sometimes.

Capitalism sucks, except when it doesn't. The problem is that it's always creating winners and losers. We would've been happy with a reasonable ROI. Double in 9-10 years is crazy in any market. What is this going to mean for people in their 20s and 30s? I hate to think of where that generation will be when they're our age.