Anna Magnani: One Of The Greatest Film Actors You May Have Never Heard Of

For American audiences, she represented "what Hollywood had consistently failed to produce: reality."

Anna Magnani (March 7, 1908-September 26, 1973) was one of those extraordinary but happy accidents of nature that spring up out of unhappy conditions. She was born in a Roman slum, the child of unwed parents, abandoned by her mother who left her for Anna’s grandmother to raise. And yet it was these hardscrabble circumstances that Magnani would eventually draw from—not to “create characters” (she was opposed to imposing an artificial construct on the characters she portrayed, preferring a “natural as life” approach) but to stir strong emotions in her audience. She represented something rarely seen on screen, especially during the post-war years: earthy, passionate, working class women portrayed by an actor in whose veins flowed the same proletariat blood. Not a beautiful young starlet “unglammed” to play a role, but the real deal, a woman embodying all the maddening paradoxes of being female, Roman, underprivileged, unloved, and soulfully human.

“I soon realized I was born to be an actress,” Magnani once said. “I became one in the cradle, having suffered one tear too many and one caress too few. All my life, I screamed with my entire being, begging to be loved with all the tears I had in me. I will only give up asking for love when I am dead. But it took so many years, so many mistakes.”

Magnani went from being a “plain, frail child with a forlornness of spirit” to a volcanic powerhouse of a performer at some point during her two years at the Eleonora Duse Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in Rome. At nineteen, she left the Academy to take a job in a touring theater company, playing ladies’ maids and other bit parts. Her salary was 25 lire a day—the equivalent of less than one dollar. Then in 1929, one of the leading ladies quit, died, or was fired, and Magnani got her first big break, performing an emotionally touching scene which earned her thunderous applause. She showed a knack for connecting with her audience—not just with her head, but with her heart.

“I hate respectability,” Magnani insisted. “Give me the life of the streets, of common people.”

“She was instinctive" an actor friend Micky Knox wrote. “She had the ability to call up emotions at will, to move an audience, to convince them that life on the stage was as real and natural as life in their own kitchen.”

For the next few years, Magnani continued to hone her craft, sometimes supplementing her income by singing Roman folk songs in cabarets. Her voice, often compared to that of nightclub chanteuse Edith Piaf, was throaty, sensual, with just enough edge to convincingly deliver the bawdiness of her material. But it was during a fiery performance of an experimental play she was doing in Rome that she caught the eye of Italian film director Goffredo Alessandrini, who found himself equally captivated by her acting chops as he was by her. They married in 1933 and separated in 1942, although their divorce wasn’t finalized until 1950.

Alessandrini discouraged Magnani’s interest in film, advising her to continue her stage work. Even in Italy, Magnani was considered too earthy, “provincial,” and not conventionally attractive. She ignored that advice by accepting minor roles in minor films that attracted very little notice. Then she was cast in Vittorio de Sica’s Teresa Venerdi as a music-hall queen with delusions of grandeur, her first important and critically acclaimed role.

During the war years of 1943, Magnani played a vegetable seller in love with the fishmonger in an adjacent stall, giving a bravura performance in Mario Bonnard’s Campo de’fiori, a role which endeared her to the Italian public. But it was Roberto Rossellini’s masterful classic of Italian neorealism, Roma Città Aperta (Open City) that made Anna Magnani a star. Her tragic character, Pina, is one of the most unforgettable in cinematic history.

Open City also attracted the attention of playwrights and movie makers from across the Atlantic. Magnani won the National Board of Review Award for Best Foreign Actress and collaborated with Rossellini on a number of other projects: L’Amore: Il Miracolo (Magnani plays a peasant woman seduced by a stranger she believes to be a saint who leaves her carrying the Christ child) and part two of that series, Un Voce Umana (a movie based on a Cocteau play where Magnani tries desperately to salvage a doomed relationship over the phone.)

Magnani and Rossellini became an off-screen item as well, a liaison doomed to failure. Rossellini was jealous and possessive; Magnani was volatile and defiant. She was also a chronic insomniac who subsisted on a steady diet of coffee and cigarettes (“My nights are appalling,” she once intimated to a friend. “I wake up in a state of nerves and it takes me hours to get back in touch with reality.”) The couple screamed at one another and threw crockery at each other’s heads for about five years until Rossellini, promising to cast Magnani in his new film, gave the role to his new lover, Ingrid Bergman. Not surprisingly, this severed their personal and professional relationship.

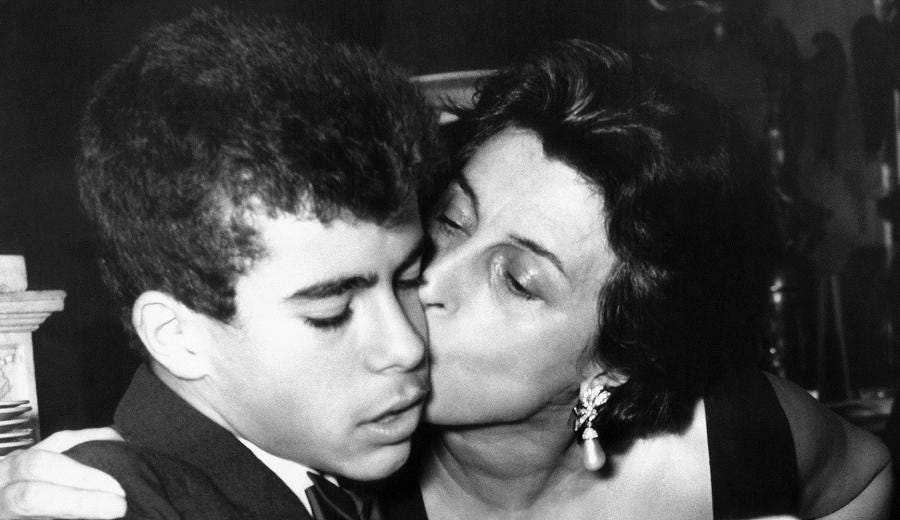

There were additional hardships. Magnani’s only child and son, Luca, the product of an affair in 1942 with actor Massimo Serato, contracted polio and would remain paralyzed for the rest of his life. In true Magnani fashion, she resolved to work even harder to earn the kind of money that might shield him from deprivation.

“Mom created herself,” Luca Magnani said of his mother. “She did this without any protection; indeed, during a time when women were forced to rely on men in order to get ahead in their careers. But not her. She broke the mold.”

Her moving performance in Open City earned her a cult following among the cognoscenti in America and attracted the notice of playwright Tennessee Williams, who wrote The Rose Tattoo in 1951 with Magnani in mind. Unsure of her English, she declined the stage role, but portrayed Serafina Delle Rose in the 1955 film version, which earned her an Academy Award for Best Actress the following year. When the Academy relayed the good news to Magnani over the telephone, it took quite a bit of convincing before she believed she wasn’t being pranked.

Magnani’s American agent, Gene Lerner, claimed, “The Oscar, to Anna Magnani, was like giving that Oscar to every single Italian. It was thanks to Anna that Americans knew and loved Italy.”

From her friend and admirer, Bette Davis: “Anna Magnani is the greatest actress I have ever seen.”

From Anthony Quinn, who worked on two films with Magnani: “A professional beast. We didn’t get along, but I would have done anything to work with her.”

As the American fascination with Anna Magnani accelerated, her popularity in Italy began to decline. Post-war Italian audiences were drawn to flirtatious comedies and prettier actresses, and Magnani was a reminder of a much bleaker period in that country’s history. And yet, according to Tennessee Williams, wherever she went there were cries of “Anna! Anna! It seemed as though Anna belonged to each of them. I consider Anna Magnani to be the most beautiful aspect of the Italian spirit.”

“She liked to drive at night, in her empty and silent Rome,” Williams continued. “She took me everywhere.” (Reading this kills me a little. It fills me with unspeakable longing. To be in “an empty and silent Rome”—when these days, it is anything but—in a car with Tennessee Williams and Anna Magnani … I mean, the heart can only take so much.)

Now a full-time resident of California, Magnani did what I consider to be one of her finest roles: Sidney Lumet’s The Fugitive Kind (1960) with Marlon Brando and Joanne Woodward. Based on Tennessee Williams’ 1957 play, Orpheus Descending, the movie takes place in the Deep South. Brando smolders as Valentine “Snakeskin” Xavier, a guitar-playing drifter, who has an affair with Magnani’s proud, lonely Lady Torrance, an unhappily married shop owner who aspires to a better life. Magnani, whose full commitment to character made her a natural fit for Williams’ Southern Gothic aesthetic, is brilliant and vulnerable in the role.

For the ambitious (or Italian speaking), I give you Magnani’s tour de force performance in Visconti’s 1951 neorealist drama, Bellissima, a satire of the postwar film industry in Italy. Magnani’s stage mother takes on a group of casting directors who have the audacity to laugh at her daughter’s screen test.

Magnani’s 1973 funeral in Rome (she died at the age of sixty-five), prompted a public outpouring of grief. Thousands of mourners came to pay their respects by throwing flowers and giving her one last burst of applause as a final farewell. Magnani would have been deeply touched by such a demonstration.

Anna Magnani, daughter of Rome, had finally come home.

Copyright © 2022 Stacey Eskelin

What are your thoughts? I want to hear them! Leave your comments in the section below.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ey9jNeKjbFo

The man woman thing.... complicated.

The film society at 5he University of Minnesota in the 70's played every single 1 of those films. There were subtitled versions available but I worry that they are no longer existent