You’re Being Brainwashed Into Thinking American Healthcare Is Great — It’s Not

The time for talking is over. We urgently need national healthcare.

Three years ago, John and I traveled to Città di Castello, a spruce, charming town snugged up against the spinal foothills of Italy, for his double-hernia surgery.

The surgery, the extra night in the hospital, all his medications, his doctors’ appointments before and after the intervento (what the Italians also call “day surgery”), and my own overnight stay in the hospital to look after him … were free.

We were stunned.

I’ve never had health insurance. Being a freelance writer, I’ve never been able to afford any, and seeing how well Italy does healthcare, particularly during a global pandemic, has been a fascinating and humbling experience.

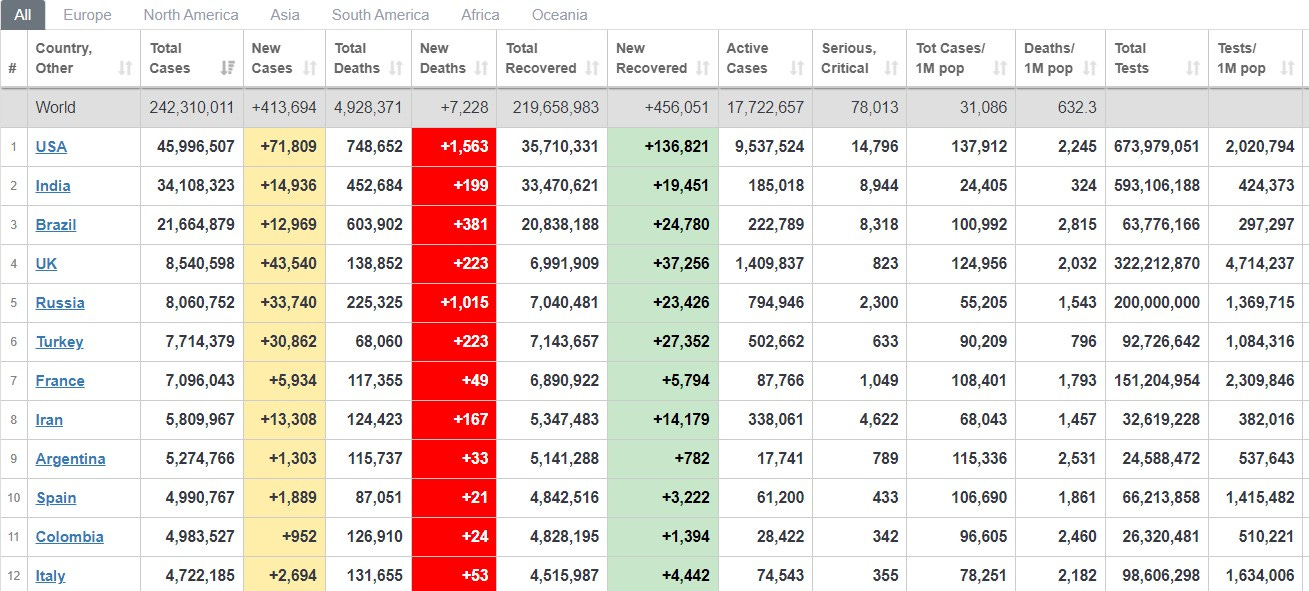

As of this writing, Italy’s daily Covid stats (53 dead) are downright impressive compared to those in Russia (1,015 dead), the USA (1,563 dead), and the UK’s up-trending infection rate (43,540).

Clearly, Italian healthcare works. But what’s really startling is the degree to which it makes our own American healthcare system look shabby.

Here’s why.

As is true of most countries with socialized medicine (and that is what we’re talking about here), Italy has a higher-than-average tax rate. But taxes aren’t the only reason Italians have good healthcare. Priorities are.

As a general rule, Europe considers healthcare to be a right, not a privilege. This is, after all, the only humane approach to an issue that can determine a person’s life or death.

In John’s case, after he was diagnosed with a baseball-sized inguinal hernia and a second, smaller hernia, he paid the equivalent of $425 USD for his tessera sanitaria, or healthcare card. Had he been Italian, of course, he would have paid nothing. Having that card opened up healthcare doors in ways we could have never imagined.

Now, instead of paying a hundred euros for his asthma medication Advair (it comes in a discus and runs about $500 in the United States, without insurance) he pays €4,00 ($5.00 USD). Most other medications are free.

In many other countries, particularly European ones, not being able to afford medical care isn’t an automatic death sentence. The standard of care here is excellent (we have only to look at Italy’s Covid stats to prove it) and Italy isn’t even a country that ordinarily prides itself on a well-run bureaucracy.

Here’s the process John went through to get his surgery.

The minute we received his health card, we made an appointment with a doctor, which wasn’t difficult. At the time, we lived in a medieval borgo called Civita Castellana, which is about seventy kilometers north of Rome. The doctor’s office, located just around the corner from us, consisted of twenty or so hard-shell plastic chairs lined up against pale green walls, a busy receptionist, and a table full of trashy gossip magazines.

There were plenty of nonnas in their sensible shoes and support hose, handbags clutched in liver-spotted hands. Non-patients and family members drifted in and out of the waiting area just to chat. Italians are a sociable bunch, and this is a community where everybody knows one another.

Here, doctors’ hours are never 9–5. Italy observes the tradition of pausa pranzo, or lunchbreak, which means the doctor is available for three hours in the morning, three hours in the afternoon, around four days a week. You can make an appointment, but most people just walk in and wait it out. That’s what we did.

It took us ninety minutes to see the doctor. What I found most amusing, besides his oh-so-Italian hand gestures and choppy Civitonica accent, is that he sat behind a table the leisurely forty minutes we spent with him, nodding sagely as John described his symptoms. He never tried to rush us. There was no physical examination. All we did was talk.

The doctor wrote a prescription for an antacid (one of the less pleasant side-effects of bilateral inguinal hernias is the indigestion) and scheduled an appointment for us to see a specialist early next week.

The specialist had bad news. The soonest John could be operated on was six months. He wasn’t going to make it six months, not only because he’s a drummer, but because he still had to function as a human being. After we got home, we remembered a fundamental truth about Italy, which is: rules are one thing; what’s possible is often something else.

Italy is composed of regions, each with its own government. We lived in the region of Lazio. What if we tried to get an appointment for a region that was less populated?

We asked around, made a few calls. In Umbria, a town called Città di Castello had a specialist who could operate on my boyfriend within five weeks. We couldn’t believe our luck.

We traveled to Città di Castello four weeks later, John went in for his pre-op appointment two days before the surgery, and then he went into surgery. His bilateral hernias were fixed by laparoscopy, reinforced with mesh, and he was released the next day. The nurses were wonderfully accommodating, especially when I asked to spend the night with him in the hospital.

Again, let me remind you, this was all free.

If the sign of a civilized society is the way it treats the least among them, we, as foreigners, were accorded the same respect and medical expertise as Italian nationals.

When my son accidentally swallowed a bottle cap in Houston, Texas, his hospital bill came to over $40,000. When another American friend broke her left arm, her bill was over $20,000. Medical insurance, even with the tattered remnants of Obamacare, can easily run $1,200–1,500 a month for two people, which is probably why 60% of even insured Americans with medical bills blow through most or all of their savings.

Yet we persist in deluding ourselves that American healthcare is the best in the world, even though most Americans, myself included, can’t afford it. We live with that flimsiest and most delusional of all hedges against disaster: hope. As in we hope we don’t get sick. And yet, I had to move to Italy to discover just how badly I’d been deceived.

No one deserves to die for what they can’t afford.

National healthcare is the answer, but no one’s going to just hand it over. We need to fight for it. Otherwise, sooner or later, we’re all looking at financial ruin.

I’d love to hear what you’ve got to say on the subject of healthcare. Please leave your comments below.

"Europe considers healthcare to be a right, not a privilege." Boom. That's it, right there. In my book, I wrote an entire chapter on the Norwegian social/healthcare system. What struck me while doing my research was how damned humane it was. PEOPLE were the priority, not profit. Here in the US, it's the opposite.

In 2010, while shooting baskets at a 24 Hour Fitness in Portland with my ex-girlfriend, I went up for an easy jump shot. As soon as I did so, I felt as if someone had shot me in my left Achilles tendon. I've known some pain in my life, but never anything like that. I knew that it was a partially torn Achilles tendon immediately, but I was unemployed and had no health insurance. Thus, I couldn't afford to see a doctor. My solution was to avoid doing anything stupid for several months and hope for the best. Unfortunately, it would be 14 months before my Achilles felt good again.

It didn't have to be that way. It shouldn't have been that way. But in America, access to healthcare is directly proportional to the size of your bank account.

Erin's a nurse practitioner in an outpatient oncology clinic, so I'm way too familiar with healthcare horror stories. We're the only country in the industrialized world without single-payer...because Republicans and insurance companies know that suffering equals profit. And there's no shortage of profits to be had.

America's healthcare delivery system sucks; we're barely Third World in many respects. Yet, in what many on the Right will argue to the death is the greatest country in the world, one can die because they can't afford treatment. That's criminal.

Meanwhile, my Achilles has never been the same. We went to a baseball at Petco Park in San Diego last month, and someone behind me pushing a woman in a wheelchair rammed it directly into the spot where the tendon tore so long ago. After 11 years, it's still sore. Would it have healed better if I'd been able to get proper treatment? It's hard to imagine it wouldn't now be in much better shape.

"America considers healthcare to be a privilege, not a right." He who has the gold gets the treatment.

Dear Stacey,

There was skiing in my first marriage. It was *deeply* problematic for me. Because my husband's parents were diplomats stationed abroad, ski vacations took place in Klosters, Switzerland, a ski resort town near Davos. They had found Klosters when they were stationed in Belgium, and my ex-husband was a child.

I am not at all athletic. I do not care where a ball goes. My love is a nice dog walk on a scenic trail. But I was not able stop taking gym before injuring my knees several times.

Despite my problematic knees, my young husband really REAALLY wanted me to ski. So I took one week of lessons and then he took me on an intermediate slope, which in Switzerland is very high up and exceedingly steep. Yep: I eviscerated my knee.

I had no health insurance at the time, because I had just graduated from grad school and my policy expired when I got my degree.

Suddenly, I needed a complicated surgical procedure, and a week in the hospital. Thank the Gods I speak German!

My operation and hospital stay cost my father in law almost $10K, which is a fraction of what it would have cost in the USA.

Furthermore, since quite a few people have the same Unhappy Triad accident I had while skiing, the Swiss doctors were experienced aces at that surgery. Every single person I have ever met who had ruptured their medial collateral and anterior cruciate ligaments, and creamed their meniscus like I did, but received surgery in the USA, had a much worse scar and less mobility than I do.

For comparison purposes, recently my husband had a three day stay in a local hospital here in Washington State. We have Kaiser health insurance. We owed almost $10K *even with health insurance* and the total bill was above $80K.

Healthcare is a human right. Europeans understand this, but a certain political party in the USA has been obstructing healthcare reform legislation for my entire lifetime, and I was born in the Eisenhower administration.

President and Mrs. Clinton tried and failed to pass healthcare legislation. Back then, I was still living in DC and doing PR for causes and candidates on the Left. I worked for a non-profit ally of the Clinton effort to pass healthcare reform.

Did you know that Nixon tried to pass healthcare reform, and failed?

Thank the Gods that President Obama succeeded. But the USA has a long way to go still.

Healthcare prices are still insanely expensive here. The system needs more reforming still, including reform to the price of medical education, and the practice of abusing residents as they are trained in hospitals. We also need reform for drug pricing: Big Pharma is just as greedy as the other healthcare sector profiteers.

So I am not surprised by the story of John's healthcare situation. But most Americans have been propagandized to believe the USA's medical care is the best there is in the world

Bollocks it is.

Healthcare is a human right.