Was Modern Art Secretly Financed by the CIA?

How Abstract Expressionism was used as a cultural weapon during America's Cold War with the Soviet Union

Post-war America was a renaissance of new art forms. From free jazz to the Beat poets, the noir-ish naturalism of movies like Eli Kazan’s Boomerang, to the spectacular rise of Abstract Expressionism, the “age of anxiety” surrounding the forties and fifties led to creative innovation like never before.

Our victory in the Pacific Theater of WWII made us giddy, giving us an out-sized belief in our own invincibility, the rightness of capitalism, and the soundness of our most cherished ideals: rugged individualism, manifest destiny, patriotic fervor. We were the heroes of our own narrative.

At the same time, our nation’s obsessive paranoia of the Soviet Union—fueled in large part by having witnessed firsthand the toughness, resilience, and effectiveness of the Red Army—told a different story. British historian and journalist Max Hastings, author of Inferno: The World at War, 1939-1945, wrote: “It was the Western Allies’ extreme good fortune that the Russians, and not themselves, paid almost the entire ‘butcher’s bill’ for [defeating Nazi Germany], accepting 95 per cent of the military casualties of the three major powers of the Grand Alliance.”

An estimated 26 million Soviet citizens died during World War II, including as many as 11 million soldiers. By contrast, the United States lost 418,500 (counting civilians). In other words, for every single American soldier killed fighting the Germans, 80 Soviet soldiers died doing the same. While American GIs returned home to a country that embraced them as heroes, the Soviets were licking wallpaper paste off the walls of their parlors, just to stay alive.

The fierce determination of the Soviets to win at any cost spooked the U.S. So did our ideological differences and the emergence of a nuclear arsenal that both sides could launch with the press of a button. While the Soviets gruffly dismissed the West as “bourgeoise capitalist swine,” the U.S. was quick to point out, not without justification, how repressive life was under Soviet rule. This was especially true of artists, who were forced to create in service to the proletariat. By order of the state, the approved style of art was Socialist Realism.

Whether all attempts to branch out from state-sanctioned art styles were quashed remains a subject of debate. But in the West, Socialist Realism was widely perceived as stodgy, provincial, and laughably idealistic. Two world wars and the Great Depression had been informing the work of American artists since the twenties, culminating in a movement that exploded in 1940s New York called Abstract Expressionism. It was the absolute antithesis of what was happening in the Soviet Union.

Scale is the signature of Abstract Expressionism. Canvases often dwarf the viewer. Many of its progenitors—luminaries such as Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, and Mark Rothko—were used to working on a grand scale, producing murals for the New Deal’s Federal Art Project. Their purpose was to create art that was abstract, but also expressive and emotional in its effect. The less “representational” the art, the better to reflect back to the viewer the unconscious mind of the artist, and to no lesser degree, that of the viewer. In other words, Abstract Expressionism was designed to be a Rorschach test, of sorts, and therefore psychologically interactive.

There were two groupings of Abstract Expressionism: the contemplatives like Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, and Barnett Newman, who strove for simplicity by using color field painting, or large areas of a single flat color. Then there were the action painters led by Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, whose paint pours and sweeping gestural style evoked less sedate emotions.

Above all else, Abstract Expressionism celebrated the individual artist’s freedom to express himself in whatever way he chose, and this was exactly why it attracted attention from the very people who most wanted to flaunt American superiority over the Soviets: the CIA.

Until recently, the CIA connection was a tenuous one, conjectural. Then a former CIA case officer named Donald Jameson broke the silence: "We wanted to unite all the people who were writers, who were musicians, who were artists, to demonstrate that the West and the United States was devoted to freedom of expression and to intellectual achievement, without any rigid barriers as to what you must write, and what you must say, and what you must do, and what you must paint, which was what was going on in the Soviet Union. I think it was the most important division that the agency had, and I think that it played an enormous role in the Cold War."

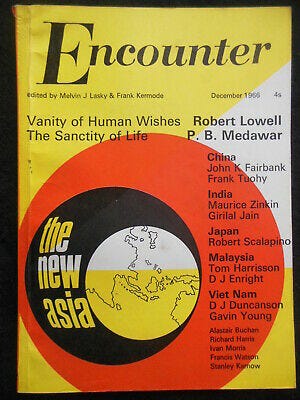

To that end, Jameson and others in the CIA created the Congress for Cultural Freedom, a consortium of poets, artists, and literati, backed by CIA money and run by a CIA agent. At its zenith, it had outreach in 35 countries and published more than two dozen magazines, including one named Encounter, a literary magazine geared toward intellectuals and the anti-Stalinist left. There is no denying it played a robust role in shaping the worldview of the lefty avant-garde.

One of the biggest hurdles the Congress for Cultural Freedom faced wasn’t exposure—it was resistance from the American public itself, and the public’s elected representatives on Capitol Hill. Fully 60% of Americans detested Abstract Expressionism. "It was very difficult to get Congress to go along with some of the things we wanted to do - send art abroad, send symphonies abroad, publish magazines abroad,” Jameson confessed. “That's one of the reasons it had to be done covertly. It had to be a secret. In order to encourage openness we had to be secret."

The CCF spearheaded several exhibitions of Abstract Expressionism during the fifties, among them a tour de force titled “The New American Painting,” which visited every major European city. As the story goes, the Tate Gallery couldn’t afford to bring the show to London since the pieces were monumental and expensive to ship. So Julius Fleischmann, grandson of yeast baron Charles Fleischmann, an American millionaire, funded the exhibition. Fleischmann was also president of the Fairfield Foundation, an archeological preservation society funded by the CIA, and less publicly, he a spy. He was well suited for art-related covert ops, since he, and several other powerful figures close to the CIA, sat on the board of the International Program of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

The artists themselves, wholly ignorant of the CIA’s involvement, were never “instructed by the government” on what to paint. Instead, their very subversiveness was weaponized to deliver a payload to the Soviets: in the West, the fruits of individual freedom were reflected in art itself. Oh, and by the way, how is your “farm art” coming along, you dirty Bolsheviks?

Would Abstract Expressionism and its even less popular cousin, Pop Art, have made it to the fore of public awareness without the CIA’s intervention? It’s impossible to say. But the movement did languish in relative obscurity until the CIA thrust it onto the international stage. Also, what might de Kooning or Pollock have thought to see the fetish America has made of the “personal freedoms” they so beautifully exemplified?

Unfortunately, we’ll never know.

For more on this subject, view Hidden Hands: A Different History of Modernism, Episode 1, “Art and the CIA.”

What are your thoughts on the CIA’s involvement in Abstract Expressionism or on Expressionism itself? I’m all ears. Feel free to expound in the comments section below.

Fascinating article. With each passing day, how we have been manipulated in every facet of our lives becomes more and more apparent. I am filled with wonder at it all.

Interesting, but I find myself wondering how much of the Abstract Expressionism found its way to the average Russian fully invested in their day to day survival?