Thinking About Becoming a Full-Time Creative? Read This First.

Way I see it, you got about five options....

There are some truly great things about being a freelance writer—and by the way, please substitute “creative of any kind” for “freelance writer,” with respect to much of what I have to say here. The work you do is often fulfilling, your commute usually consists of shuffling from the bed to your computer, and the best part is pants are completely optional.

Other perks: you usually answer to no one but yourself, which is good for those of us who don’t easily suffer fools or play well in the sandbox with others.

Lots of creative ventures (theater, moviemaking, live music, dance) are collaborative efforts. Not writing. It’s you, creating something from nothing. You pull it out of thin air—or your own derriere, depending on how much it stinks.

But if you aren’t a trust fund baby, an amply provisioned retiree, or married to a gainfully employed and wonderfully supportive spouse, you are depending on that freelance writing to pay your bills.

And that, my friends, is a huge problem.

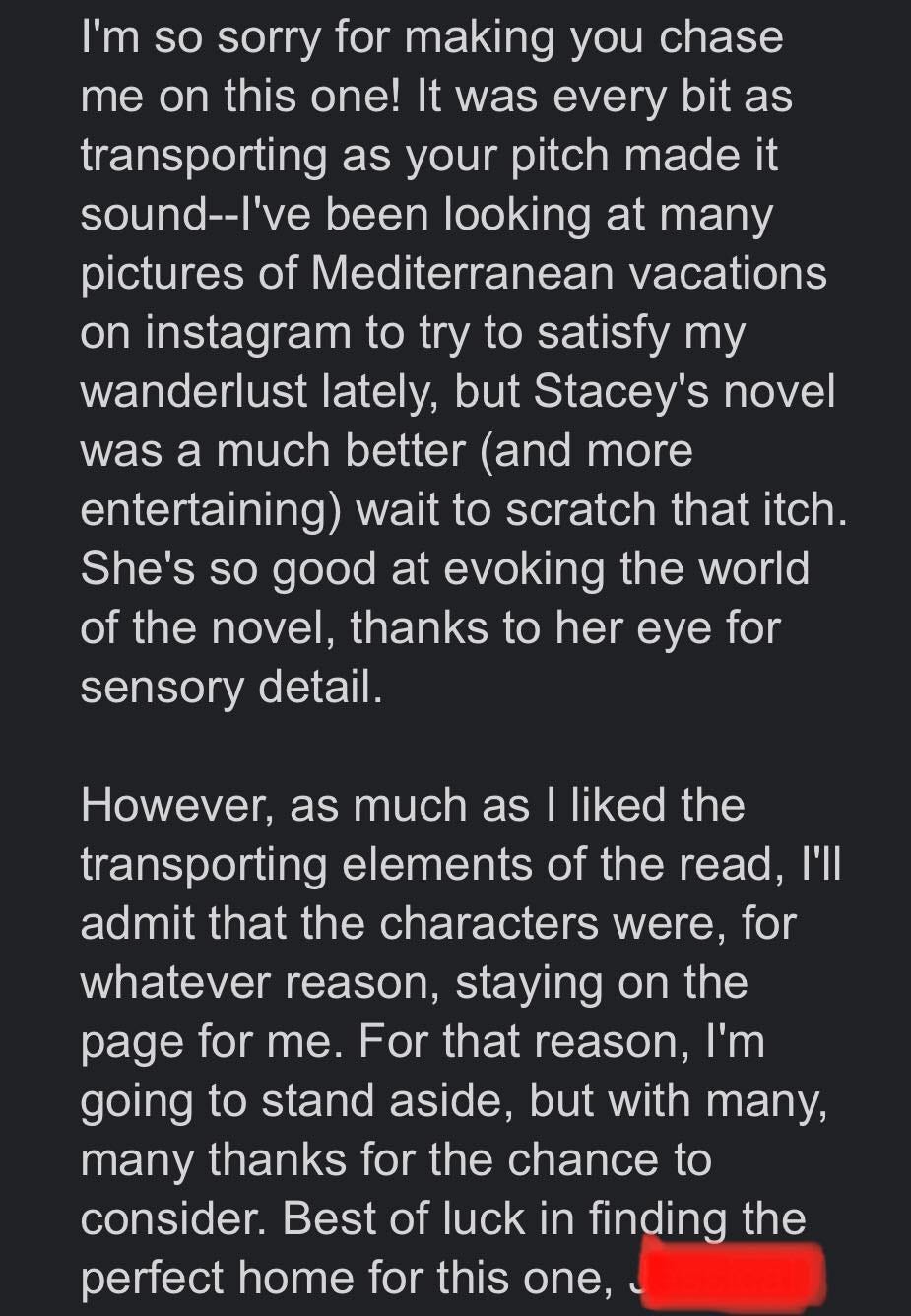

Right now, my agent is shopping THE GROWING SEASON, my upmarket women’s fiction novel, to various publishers. Editors have inventive ways of saying no—the characters “stayed on the page for me” (this is bad), “I loved it, but I didn’t love it enough”—yet it all amounts to the same thing, which is an emphatic no.

Fortunately, no doesn’t deter me.

At this point, few rejections bother me like they used to. Rejection is part of the dance. Editors are the gate-keepers of my industry, and they’re not evil. They simply have prejudices and preferences, just like the rest of us. You can’t get mad at Simon & Schuster or Putnam or anyone for favoring the taste of chocolate over vanilla. And it’s their job on the line if they agree to buy your book and it ignominiously flops.

What bothers me far more than rejection is the degree to which my work is constrained by the demands of the marketplace. I make my living by the pen. I can’t write exactly what I want to write (which would be nerdy historical). I can’t afford to, not if my story idea has negligible commercial value. I have rent to pay. If a writer doesn’t keep an eye on trends in the marketplace, she’s probably not going to find a publisher.

In his remarkable essay, Why Real Art is Priceless and Most Artists Are Poor, writer/philosopher Benjamin Cain states: “The most popular products make for the highest sales, but those products are almost never the highest in quality, according to artistic standards of evaluation. Of course, if you define “value” subjectively in terms of whatever people pay for … then Michael Bay or superhero movies are better than those that win Oscars or that film critics praise. Likewise, the vacuous self-help books that are Amazon bestsellers would be superior to philosophical classics.”

If art and commerce are incompatible bedfellows, what’s the answer? Do we allow the marketplace to dictate what kind and what quality story we write, song we compose, ballet we choreograph? Or do we go in the opposite direction—write what we want to write and hope somebody “out there” likes it? That seems like a precarious way for anyone to make a living. What does it say about a society that not only fails to subsidize the arts, but actively defunds them?

As far as I can see, there are several possible roads a creative might take.

Going fully commercial. Don’t worry about art—just go for the bottom line. Hey, it beats working at Wal-Mart, right? Writing purely commercial fiction is at least marginally creative. There’s no guarantee you’re ever going to make a living though, whether you self-publish or traditionally publish. In a post-pandemic world, there are a trillion books just like yours vying for the eyeballs of a jaded public. So, if you dive into those waters, be prepared to swim hard and for a very long time.

Writing as a side hustle. At first blush, this seems like the the smartest move. You have your day gig to pay the bills, and then you write when you have time. There are plenty of people who made this work—name-brand author John Grisham used his morning train commutes to write his early books. But not everyone has the kind of job that leaves them emotionally and psychologically intact. Most jobs are exhausting, and doing any kind of creative work requires focus and a powerful amount of self-discipline. Is this really a viable option for you?

Applying for grants or any kind of artist funding. In my experience, the fiercest gatekeepers are the ones gargoyling the coffers. Getting a financial subsidy is as daunting and soul-crushing as attempting to find a publisher for your book. It’s also time that might have been better spent writing. Odds are, your efforts will not be rewarded with cold hard cash, and you’ll starve trying.

Writing on a platform like Medium, Patreon, Substack, etc. I’ll give this a strongly qualified … maybe. As in, it may be muddle-headed idealism on my part, but I believe it’s possible to gain a following by serving your work in free, easily digested, bite-sized pieces. Long form reading (such as a novel) requires time, money, and energy that not everyone is willing to commit to unless they know you’re worth the effort. Consider your blog to be a starter drug. Give readers a taste, and they just might want more.

But the problem with platforms such as these is they’re tricky to monetize. Not everyone can afford $5.00 a month for your blog. A major news organization like the New York Times is actually half that. For a variety of reasons, many of them humanitarian, I’ve chosen not to paywall my articles. I offer them to free to anyone who wants to read. And I’m fortunate enough to have friends and fans who have the means to contribute if they want to. Thanks to superb bloggers like Elle Griffin, whose Substack, the Novellist, I’m a huge fan of, I might decide in the near future to serialize some of my fiction and put it behind a paywall. But it could be a long time, if ever, before I pay my bills with the proceeds. In other words, Cappuccino is a labor of love, not a bucket of cash.

Self-publishing. There’s one self-published book in my repertoire, and getting it out there was a Herculean task. Some of us (not me) are better at formatting books than others. I self-publish about as effectively as I shop, wrap gifts, or tote small columns of numbers, which is to say I absolutely suck at it. And that’s not even the hardest part. The real challenge is getting your book noticed amid the din and clamor of a million other books. It’s demoralizing. That my self-published memoir has done as well as it has is a fluke, an aberration, a word-of-mouth phenomenon that still hasn’t yielded enough of a profit to support me.

Self-publishing is also expensive. Hiring a developmental editor/line editor can be pricy (I do this kind of work, but I don’t usually discount my services, simply because performing the job to a professional standard is so time intensive), and if you want any credibility at all with your reading public, you should also hire a professional to do your book cover. If you wish to advertise, that costs money. So does purchasing an ISBN number, which you will need if you want to publish on platforms other than Amazon.

Self-published writers who succeed at making money that, you know, actually folds are those who either write in collaboration with others to crank out new books every 4-6 weeks or can keep to a similarly tight publishing schedule on their own. Even so, it might be years before you’re able to support yourself doing this kind of work, and per market dictates, genres like horror, romance, and YA sell a lot better than “quieter,” more literary books.

The older I get, the more of life I see, the more convinced I become that art and commerce are not necessarily mutually exclusive, but they rarely cohabitate. If you’re going to go pro as a creative, and you don’t have a secondary means of support, you would be wise to keep both eyes firmly affixed to the market, fickle though it is. I have ideas sometimes that writing commercial fiction “pollutes” my instrument, but I think that’s mostly hogwash. Know how you get better as a writer? By writing. Full stop. Being all dainty about what you write is pretty much guaranteed to get you nowhere.

Do I wish I’d majored in Finance in college and was now sitting on a fat nest egg? Yes. Having devoted less time to learning how to write, would it have delayed my proficiency? Yes. Do I wish Creatives, who play an outsized role in society and deserve better financial support, actually got it? Hell to the yes.

I have no wish to curb your enthusiasm; merely to recalibrate your expectations. Freelancing is hard. Substack, Patreon, Medium and the rest may have eliminated the gatekeeper and democratized the virtual fairground so that all Creatives can participate, but there is an awful lot of dreck out there, and without a way to sort through it, consumers will have a tough time finding you. By going your own way, you also sacrifice the prestige of “being published” by a traditional publishing house. Having a Big Four publisher’s colophon on the end paper of your book is a big deal to writers. Unfortunately, even with that stamp of approval, you will face all the same daunting marketing challenges that you would if you’d self-published.

I don’t have hard numbers on this, but I suspect at this point there are more writers out there than there are readers. Therein lies the rub. Don’t get me wrong—stories will always be popular. It’s the way we consume stories that’s changing and the trend seems to be veering away from words and toward visuals. At this point, I’m just hoping books don’t become obsolete.

What are your thoughts on the subject? Please leave them in the comments section below.

While I have you, not everyone can afford to support Cappuccino by giving a monthly or yearly contribution, but everyone is capable of sharing the articles you read here. Right below this paragraph, you will find a small box with an arrow pointing up. Feel free to click on that icon and use it to share the articles you most enjoy. Thanks for your support.

If you've not already, you might look into Samuel R. Delany's essays. While he is a science fiction author, his discussions of the issues facing genre writers carry over. Joanna Russ, a truly brilliant author (my phrase: the Iris Murdoch of science fiction), yet she never once made enough money on her writing to survive. Genre writing will casually outsell the lead titles on the NYT's "best seller" list, and yet they won't receive a glance, much less a mention, because they are not "serious."

By the bye, I actually made something like $60.00 -- $63.00 on my first scholarly book, which is pretty unheard of in academic circles. And the second academic work was a true collaborative effort. While each of us was the lead author on most individual chapters, we combed through every one of those chapters one word, one punctuation mark at a time. (And chapter 9 we've hardly any idea who wrote what: we were literally composing sentences together on the fly.)