Things That Will Blow Your Mind About Mexico's Day of the Dead

From sugar skulls to grinning skeletons, Mexico does death like no one else

The first time I went to Mexico, I was just a kid. Five, maybe.

I won’t lie—it affected me.

The empty scrub land that stretched for miles in all directions. The shadow of a condor rippling over sun-bleached sand. A lazy pump jack I spotted in the distance, dipping its rusty beak into parched, stingy soil.

These were all childhood impressions. I stared out of the window of our car and took them in.

Without vocabulary at the time to describe what I was experiencing, I felt, rather than understood, the hideous, desperate poverty: men on the side of the road selling colorful Mexican serapes, handmade tamales, hammered brass plates, brightly woven ponchos. All beautiful, happy things that seemed tragically at odds with their eyes.

I felt a sense of despair not wholly unrelated to our reason for being in Mexico. My mother headed a rock band, and her singer, Johnny, a sweet young man in his early twenties with a wife and four children to support, was losing his battle with cancer. The treatment wasn’t working, and my mother was desperate to save him. When she heard about Laetrile, then promoted as an alternative cancer treatment and only later disproven, here was a last straw at which she was willing to grasp.

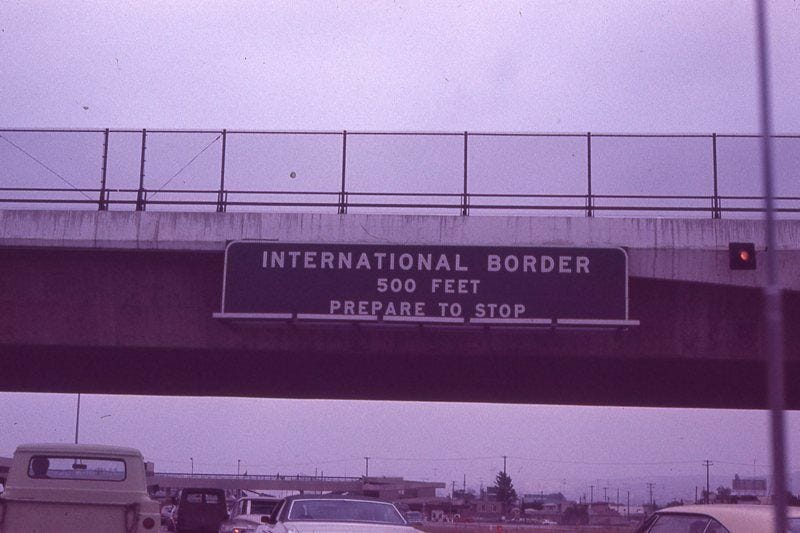

Since Mexico was the only place Laetrile was available, we all got in the car, drove over the border, and smuggled it back under our jackets, T-shirts, even our underwear. I remember the intoxication of doing something against the rules, the grownups’ distrust of authority, and the hours’ long line at the border security checkpoint. That was where the poorest of the poor hawked their wares in the heat and the dust and the exhaust fumes from hundreds of cars, their misery sounding even to my ears like a silent scream in the desert.

Johnny died not long after that, too sick to even take the Laetrile, and it broke my mother’s heart. Being as I am a conduit for other people’s emotions, I grieved, too, although death itself was a bit of an abstraction to me. I understood the irreversibility of death, but I hadn’t really put it together yet, how the ones we love can die, and yet we ourselves must soldier on without them, pretending we’re alive when we’re really not. Even now, knowing what I face, what we all face, I find myself resisting, turning away, unwilling to acknowledge the eventuality of that one final gasp.

As it turns out, Mexicans not only stare intrepidly into death’s sunken eye sockets, they celebrate it raucously, joyfully. There is an entire tradition that has sprung up around Dia de Los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, that feels so much healthier than my emotionally stunted, gringo efforts to keep pretending death doesn’t exist.

In Mexico, the Day of the Dead is actually a three-day holiday encompassing All Hallow’s Eve, All Saints’ Day, and All Souls’ Day, October 31-November 2.

And in the most Latin way possible, they go all out.

First is the purpose of Dia de Los Muertos itself, which is to assist the dead on their journey through the afterlife. It’s one of Mexico’s most important celebrations, not entirely sanctioned by the Church, but looked upon with an indulgent eye. Friends and family hold all-night vigils of prayers and feasting in cemeteries across Mexico.

During Day of the Dead celebrations, graves are decorated, coffee (or stronger libations) are served, and stories of the deceased are told far into the night—not disrespectfully, but with none of the hushed reverence we gringos feel a solemn occasion demands. And that’s because the Mexican attitude toward death is so radically different from ours. Different and better.

They use humor to recognize that death is an equalizing truth that no one escapes. Death isn’t laughed at as a hedge against fear or grief. Laughter isn’t the same as whistling past the graveyard. Death is actually invited into the body in the form of calaveras. Even children eat calaveras, which are sugar skulls that have their names printed on the forehead. They are a reminder that death lives inside each one of us, and by accepting its proxy, the death skull, we are making peace with our inevitable fate.

That’s the beauty of Dia de Los Muertos. Death constantly lives within us in the form of a calaveras, a skull, a skeleton. We can never escape it. We all carry death inside us, every second of our lives. It’s this proximity that inspires a joyful celebration of life and death. But there is a certain amount of pointed aggression toward the upper classes to it, too.

Death is the single most democratic institution in the world. Mexicans not only understand this, they delight in it. Death is an equalizing truth that no one escapes, rich or poor, pauper or king, the oppressed or the oppressors. Calaveras are often depicted in humorous hats, or as clowns, inviting the wealthy to laugh along with them—but only with the understanding that one day the dust from when they sprang will soon reclaim them, no matter how much worldly glory they enjoyed on earth.

Meanwhile, the poor take delight in their sugar skulls, their cemetery vigils, and their ofrendas, or shrines. Ofrendas, usually constructed on a table, consist of rosaries, pictures of saints, totems of significance (books, cigarettes, liquor) once beloved of the deceased, milagros (charms), statues of saints, and plenty of flowers. The perfume of flowers and incense are believed to entice spirits into the house.

Ofrendas are often created in the home of the one who died. In Veracruz, an ofrendas might be made of banana leaves, sugar cane, and palm. In other Latin countries, elaborate papel picado (cut paper) is placed around the altar.

Calaveritas or “little skulls” are short satirical poems or mock epitaphs intended for the living based upon this cultural aesthetic of social defiance and humor. Published in a pamphlet dated 1905 comes a description of the common fate that awaits all humanity, translated thusly:

Grand Dance of the Skulls

There will go the lawyers

With all their vanity;

There will go the [university] faculty

And the certified Doctors

In mixed-up confusion

Will be the skulls,

And even the straw mat makers

Will enjoy the occasion.

It will be a great equality

That levels big and small

There will be neither poor nor rich

In that society.

In this widening world

Gold perverts everyone

But after death

There are neither classes nor rank.

As far as social justice goes, you have to admit it’s an effective way to remind those who would turn their backs on the suffering of others that death never takes a holiday. No wonder Dia de Los Muertos is celebrated in such a loud, tumultuous fashion. Celebrants even wear shells on their clothing, so that when they dance, the clattering will wake the dead.

The dead are lonely. What if it’s time we all made them feel something?

Do you have any Day of the Dead stories, thoughts, or observations? If so, I’d love to hear them. Feel free to chime in below.

Caterina is the icon that is often used to identify the day. The national dia de los Muertos museum is in Aquascalienete, Mexico. An amazing place to visit!

I believe the picture at the top one 1st prize in this year's contest, possibly in Mexico City itself. (It came up on another friend's FB post right around the 31st.)