The Time-Honored Italian Tradition of Denouncing Your Neighbors

It's called a denuncia, and it's one of the most Italian things about Italy

When I first met John in 2012, he was living in an artists’ colony about seventy kilometers north of Rome called Calcata Vecchia. It’s a good story, if you haven’t seen it already, one that got picked up by a few national publications. You can read it here.

Calcata Vecchia is referred to by suspicious locals as a paese dei fricchettoni, or “village of freakish hippies,” not entirely without reason. About sixty people live there year round, and the most diplomatic thing you can say about most of them is that they’re “Bohemian” (read: crazy). Not all, but enough. There are near-daily brawls in the piazza. Some months ago, one of the resident Calcatatese slopped gasoline over the village and threatened to set it on fire. During just my two-year tenure there, I walked down to the parking lot and found the smoldering remains of a vehicle. Twice.

Most buildings in Italy, including those found in medieval villages like Calcata, are multi-use buildings. John’s flat was situated above a restaurant called Il Graal. His balcony afforded him a bird’s eye view of the neighbors directly across from him, separated only by a cobblestone artery that led off from the main piazza. One of those neighbors was a man named Dario, who looked like Ned Flanders of Simpsons fame, except Dario was absolutely bonkers.

Dario had a stoic Roman wife, a kid who constantly screamed, and no ostensible means of employment except the odd handyman job for which he mercilessly overcharged. But he had plenty of animosity for the other villagers. On the day of their homeowners’ meeting, he concluded, as a renter, that their meeting was exclusionary and offensive to people such as himself, so he flung open the windows of his apartment, pointed his speakers toward the piazza, and played Pat Metheny’s “Are You Going With Me” over and over for three hours until everybody’s ears bled. Worse, he locked himself in an upstairs bedroom and aggressively played the bongos so he couldn’t hear people banging on his downstairs door.

The homeowners’ meeting went on as scheduled, but the villagers were angry with Dario. Angriest was the Contessa, an ancient Neapolitan woman with paint-peeling gas and a sour disposition. She planted herself on the steps beneath his house, both hands folded on top of her cane. When Dario finally emerged from his lair, there was the Contessa scowling at him.

“Leveti, vecchia mafiosa!” he shouted at her. Get up, old woman who’s associated with the Mafia.

Since the Contessa was indeed Neapolitan and therefore sensitive to slights about her heritage, she got up in a fury and yelled, “Ti denuncio! Ti denuncio!” I denounce you. And in Italy, a denuncia is more than a ringing verbal denouncement against another person. It’s a formal complaint, one that’s legally filed with the local constabulary.

In other words, a denuncia is an actual thing.

Curiously, a denuncia can be lodged anonymously against any offending party, which is why they’re thrown around these parts like so much confetti. An Italian citizen is perfectly within his rights to pick up the phone and call in a complaint. Otherwise, orally or in writing, he would march into a police station, share personal details of himself as the offended party, deliver the history of what happened that offended him, and then sign the document, which is dutifully filled out by an officer of the law. And that’s what the Contessa did.

A year went by. Then another. John received notice from the court saying he was being called as an eyewitness when a court date was eventually approved. Three years passed, then four. Having worn out his welcome, Dario took his wife and kid and moved out of Calcata.

The Contessa surprised everyone by dying. No one thought she would, actually. Some people appear incontrovertible, like the sun’s rising. When they finally pass, it’s not so much a hole they leave in the fabric of people’s hearts as a knife to their most hidebound expectations for that person’s longevity. She was put to rest. Everybody else went about their business.

More than five years after the Contessa took out her denuncia against Dario, John received a summons to go to court, which he ignored. Five years. That’s how flooded Italian courts are with lawsuits, denuncias, and sundry other frivolities.

For the longest time, I didn’t understand denuncias. I’ve been called far worse than “an old woman who’s associated with the Mafia.” In fact, I can’t think of anything someone might call me that would compel me to do more than flip them off. As an American, I’m used to gross incivility. But this is Italy, where these things are taken with the utmost seriousness, and I think I finally understand why: the Italian social construct of bella figura and the very real consequences of being gossiped about in a small Italian village.

Bella figura is fundamentally antithetical to the way your average American is raised to think. With us, it’s all bootstraps and manifest destiny. With Italians, it’s bella figura. Literally, the words translate to “beautiful figure” or making a nice appearance, but it’s so much more than that. Bella figura is about dignity, hospitality, and politeness, especially how these qualities are presented to the world and how that behavior reflects on your own family. It’s why Italian women don’t wear sweatpants, activewear, or flipflops out in public.

Worrying about projecting the wrong image is especially true in small villages like my borgo of Amelia. No one has any secrets here. No one.

Without prying, caring, or showing any curiosity on the subject, you will discover things about your neighbors you wish you didn’t know. How much they drink, for instance. If they’re cheating on their wife or husband. Who they’re cheating on their wife or husband with. The list goes on. One night last summer as we trundled home from dinner at a friend’s house, John and I passed by the open window of a woman engaged in the most explicit video call in the history of Skype. The window was above eye level, but trust me, we could hear every word, along with groaning and panting. This is what happens when you live on top of one another in a 20-acre village enclosed by a 6th-century wall.

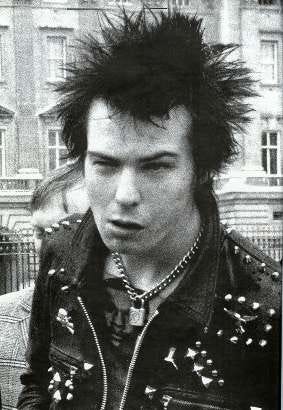

If you think about it, few things in life are more ridiculous than sex. Even Sid Vicious from the Sex Pistols admitted it was “two minutes, fifty-two seconds of squishing noises. It shows your mind isn’t quite clicking right.” Now, you might wonder what happened to this woman’s bella figura, but I promise you, she was already too far from home to care. Or she might have been one of those rare creatures who couldn’t give a fig about bella figura.

But lots of other people do. When you live in a small village, you can’t afford not to. Americans are, of course, held to a different standard, so the rules don’t necessarily apply to us in quite the same way. But we are certainly subject to scrutiny among our own. Expat communities across the country are rife with gossip, backbiting, and internecine warfare. It’s no different than high school. It’s why a dear friend of mine only half-jokingly extols the virtues of never leaving her house. It’s why other friends of mine exist in a constant state of social paranoia. It’s why they make themselves miserable trying to decipher indecipherable social cues.

I went down that road once or twice myself, being in Italy. In the U.S., where we live lives of suburban and urban isolation, these are not daily concerns. Then I realized that I’m not responsible for other people’s perceptions of me. What they think of me is none of my business.

And again, the words of Sid Vicious echo in my head: “It’s not really my problem if they think I’m weird.”

You know I love to hear from you! Leave your comments in the comments section below.

I've a real issue with neighbor noise. It is now 22 years since I lived in an apartment building where that might even possibly be a problem. (I lived in an apartment building for one of those years, during my brief "academic tinker" phase. But it was a pretty tonied up place with well built walls, floors, and ceilings.) I really dread the thought of moving into a place where the neighbors think the "10" setting on the volume control is there because sharing is caring.

I have, in the past, had occasion to confront someone who thought they owed no consideration to the rest of the world. Those were all pretty tense moments. Given that I've become less patient with age, I'd rather live in a cabin in the woods than set myself up for such encounters again.

"It’s not really my problem if they think I’m weird." OMFG, if I obsessed over that I'd have lapsed into alcoholism or drug addiction decades ago. I know I'm weird, so I assume everyone else does as well. But you have to reach a point where you no longer care what others think of you, because you can't control most of that. Of course, I'd like to be know as a good, kind, caring, and compassionate person, but I suspect there are more than a few folks out there who think I'm a flaming asshole.

And I'm OK with that.

Sometimes I like to keep people guessing.

I grew up in a small town (<1000 people) in northern Minnesota. Yeah, we pretty much knew everyone's secrets. Truthfully, most of them weren't all that interesting, but you make what you can out of what you have to work with.