The Strange and Disturbing Story of John W. Polidori, Creator of the Vampire

Contrary to popular belief, Bram Stoker was not the originator of vampire fiction.

I rarely covet.

Handbags, shoes, jewelry—these things leave me cold. I used to castigate myself for my lack of interest, assuming I had no feminine instincts. Or taste. But that’s not it—or if it is, that’s only half the reason.

It turns out what I want is just … different. This authentic 19th century vampire-hunting kit that just sold for $20,000 at auction, for instance. The minute I laid eyes on it, the spirit of covetousness rose within me. I love this kit. I would build a reliquary and pay homage to it. It’s the coolest (and yes, stupidest) oddity ever, right up there with my bizarre love for the Bob’s Big Boy, well worth the 20 large it sold for.

I’m a nerd. Nerds like weird stuff.

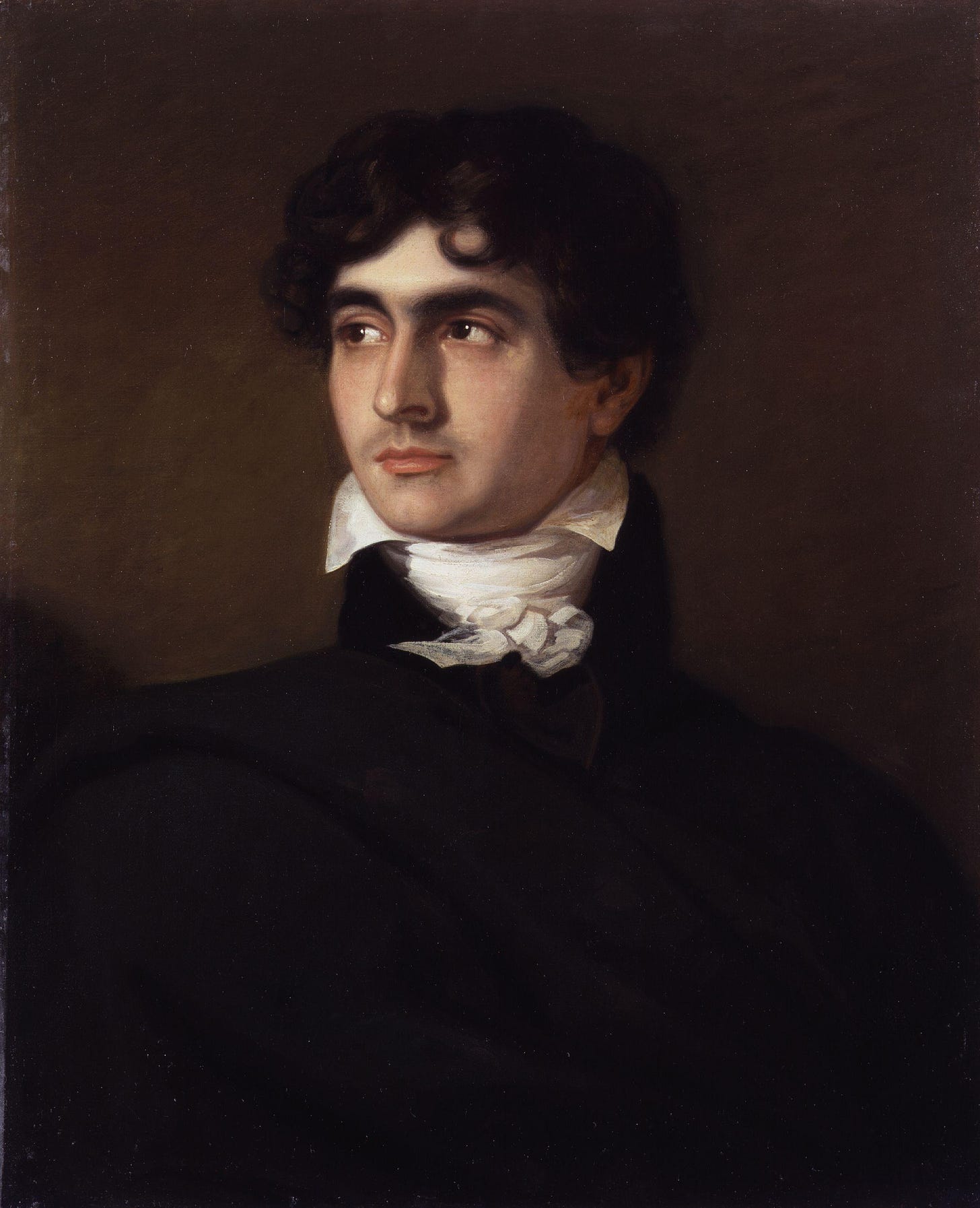

But it got me to thinking about vampires and the 19th century from whence they came, specifically vampire creator John William Polidori, Lord Byron (the prototype for Polidori’s vampire), Mary Godwin (soon to be Mary Shelley), her lover Percy Bysshe Shelley, Claire Clairmont (Mary’s stepsister and rival for Shelley’s heart; also Byron’s mistress) and that fateful summer when their extraordinary meeting of the minds produced Mary’s Frankenstein and Polidori’s The Vampyre.

Were I presented with one of those Faustian bargains (i.e., one’s soul in exchange for the heart’s desire), this is what I would sell my soul for: to be a fly on the wall that stormy night at Villa Diodati in Geneva, Switzerland, when Byron challenged everyone to write a ghost story.

It had been a strange summer. On April 10, 1815, Mount Tomboro in Indonesia had erupted, the most powerful volcanic eruption in recorded history. As far away as the British Isles, harvests failed, global temperatures plummeted, and people starved. It was known as “The Year Without a Summer,” and driven indoors by the incessant rain, Byron and his houseguests sat up into the wee hours writing their respective tales.

To an observer, the group might have appeared calm and quietly productive. Underneath that seeming placidity, however, emotions were as volatile as Mount Tomboro.

Lord Byron’s teenage mistress, Claire, now in the first weeks of pregnancy with his child, was angry at his indifference. Shelley found himself unable to write, likely due to his admiration for and envy of Byron’s talent. At one point during the evening, Shelley went shrieking from the room and had to be sedated with ether. Apparently, he’d had an eerie waking vision of Mary Godwin’s nipples turning into eyes.

To be fair, Byron had been reciting Coleridge’s quasi-homoerotic poem, Christabel, wherein the eponymous heroine brings home a woman of the forest, watches her disrobe, and is spellbound by her beauty … until realizing the woman is a witch.

Beneath the lamp the lady bowed,

And slowly rolled her eyes around;

Then drawing in her breath aloud

Like one that shuddered, she unbound

the cincture from beneath her breast;

Her silken robe, and inner vest

Dropt to her feet, and in full view,

Behold! Her bosom and half her side—

Hideous, deformed, and pale of hue—

But the real sufferer wasn’t Shelley; it was John Polidori. He was in the throes of a romantic obsession with Mary, and sadly for him, that attraction was one-sided.

A week before, as Mary struggled up a wet garden path to Villa Diodati, Byron had heartlessly suggested to Polidori that he jump off the porch to assist her. Twenty-year-old Polidori gallantly leaped the eight feet to come to her rescue, but twisted his ankle. He was forced to lean on Mary as she led him, hobbling and humiliated, to the house.

Confined to the couch for the remainder of that week, Polidori had plenty of time to brood over Mary’s perfections: her mysterious sidelong glances, her mass of honey-colored hair, her “great tablet of a forehead and white shoulders unconscious of a crimson gown.” Unable to bear it even a moment longer, Polidori confessed his love to Mary, who received his addresses with her usual serenity. Her heart, she told him, not unkindly, was and would forever be Shelley’s.

Like many young men in love, Polidori remained undaunted. Now all he had to do was impress Mary with his verbal stylings. While she began the first draft of her legendary novel, Frankenstein: or the Modern Prometheus, Polidori sat beside her, gusts of wind battering the windows, candles flickering, and penned his own tale of Gothic horror.

Writers are motivated to do their best work for a variety of reasons, whether love, fear, or filthy lucre. Unfortunately for Polidori, he’d lost ground earlier that week and was desperately trying to recover it. Byron had offered to listen to him read the first draft of his new play. “Worth nothing” was the heartless consensus opinion, which did nothing to improve Polidori’s mood.

But now with his vampire tale, he felt as though he finally might be onto something—and he wasn’t wrong. By fusing vampirism with Gothic Romanticism, he not only became the progenitor of the modern vampire novel, he lit a fire in the imaginations of millions of readers across two centuries. While it’s true that glittery vampire boys like Edward Cullen from Twilight sprang fully formed from this genre, so did objectively better fare like Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

Moreover, Polidori did a very clever thing.

He avenged himself against Lord Byron by making him the vampire.

Polidori’s creature of the night passed himself off as nobleman Lord Ruthven, a name already attached to Byron. Byron had once been involved with Lady Caroline Lamb (who famously referred to Byron as “mad, bad, and dangerous to know”). Lady Caroline wrote a roman-à-clef titled Glenarvon, which featured a Byron stand-in character named Clarence de Ruthven, Earl of Glenarvon. The novel added burnish to Byron’s notoriety. Polidori took that notoriety and gave it a very sinister slant.

Polidori was a physician by trade. Of Italian and English origin, he graduated from the University of Edinburgh where he received his degree as a doctor of medicine. From there, he entered Byron’s service as his personal physician and traveling companion—and secretly as a spy for publisher John Murray, who paid Polidori 500 English pounds to keep a “diary” of his travels with Byron.

Unfortunately, Polidori’s humorlessness made him an object of ridicule to Byron. Shelley, too, sharpened his claws at Polidori’s expense. Whether this had to do with Polidori’s personal defects or his puppy-dog devotion to Mary is lost to history. But at Shelley’s urging, Byron cut Polidori loose.

By strange coincidence some months later, Byron ran into Polidori who was crossing the alps on foot with his old sickly dog, heading to Italy to stay with relatives. Even the sight of a ragged and emaciated Polidori wasn’t incentive enough for Byron to invite him inside his coach. Byron went rumbling down the road, and Polidori haltingly made his way to Pisa.

The Vampyre was published in the April 1819 issue of New Monthly Magazine without Polidori’s permission. To make matters worse, the editor, hoping to cash in on Byron’s fame, attributed the 84-page novella to him. Neither man was happy with this decision. Byron made every effort to remove his name from the novel, but to no avail. The work was a smash success, running through numerous editions and translations—except that poor Polidori never received the credit.

In a swoon of depression over gambling debts, more doomed romances, and the poor reception of his Creation poem, The Fall of the Angels, Polidori took his own life on August 24, 1821, at the age of twenty-five. Few mourned him. But his legacy as a writer—and as the relative of other extraordinary writers—continued long after his death.

Here in my village of Amelia, not twenty yards up the street, is a building that bears his family’s name.

It is not unreasonable to assume that a member of his vast tribe staked a claim here a few centuries ago. Every time I pass by, I think about John William Polidori and his unrequited love for Mary, mother of the science fiction novel.

Sometimes, as fate would have it, our worst enemies are ourselves.

Copyright © 2022 Stacey Eskelin

I would love to hear your thoughts! Please leave your comments below.

Do we think the Polidori in Amelia is a direct connection?

I loved this for so many reasons and, yes, I want that kit, too!

First of all, Buffy the Vampire Slayer is genius. One of the reasons we are in Italy at all is that we are friends with the actors John Pankow and his wife Kristine Sutherland. They were the first people we stayed with. Kristine was Buffy's mother. (They live near Spoletto). Kristine, by the way is a great photographer.

When Henry Fielding, at the time the greatest actor in England, bought the Lyceum Theatre in London, he turned over the running of the theatre to his stage manager, one Bram Stoker. Stoker wrote Dracula, while he was putting shows on.

All that pining away for someone you can't have. We are driven to that by our bodies. Not that I don't have the pand every once in a while, but being on the other side of that is a blessed relief!

That vampire-hunting kit looks serious. I have to assume it comes with a silver bullet, no??