The Night That Changed Rome Forever

In 1958 at a restaurant in Trastevere, an impromptu striptease ruined lives.

(Warning. This article contains mild nudity.)

Her name was Aiché Nanà (pronounced: Ah-ee-KAY Nah-NAH) but she was born Kiash Nanah in Lebanon to Armenian parents, a woman of almost feral charisma with tumbling black hair and flashing eyes who craved attention the way some people crave alcohol. At the age of twenty-three, already married to Italian film director Sergio Pastore, Aiché skirted the peripheries of the idle rich, a café society of artists, actors, and louche nobility who smoked Galois cigarettes and drank the best champagne, who amused themselves with a variety of love affairs, whose beautiful faces, best seen in profile, were eagerly snapped by a slavering horde of paparazzi.

Aiché wanted admission to this demimonde, but had not yet been able to achieve it. Then on November 5, 1958, she and her husband were invited to a star-studded bash at the Rugantino, a restaurant/club in the artsy, fashionable Roman neighborhood of Trastevere.

Everyone who was anyone was there, including luminaries from culture, politics, and entertainment: actresses Linda Christian, Elsa Martinelli, and the incomparable Anita Ekberg, who at one point kicked off her shoes and did the cha cha on a table; Enrico Lucherini, the famous press agent; brilliant jazz pianist Umberto Cesari, who was performing with his band; and Tazio Secchiaroli, king of the celebrity photogs.

Over 150 people arrived, ostensibly to celebrate the 25th birthday of Countess Olghina di Robilant, but in fact to see and be seen by the kingmakers of fifties’ Rome. The room was packed, a dizzying intoxicant of perfume, hairspray, and cigarette smoke. Umberto’s group, billed as The Roman New Orleans Jazz Band, wailed onstage, adding a pulsing, sinuous beat to the conversations. In this pressure-cooker atmosphere, Aiché felt she had to compete for attention with the most beautiful women in Europe, women like Anita Ekberg. What was she to do?

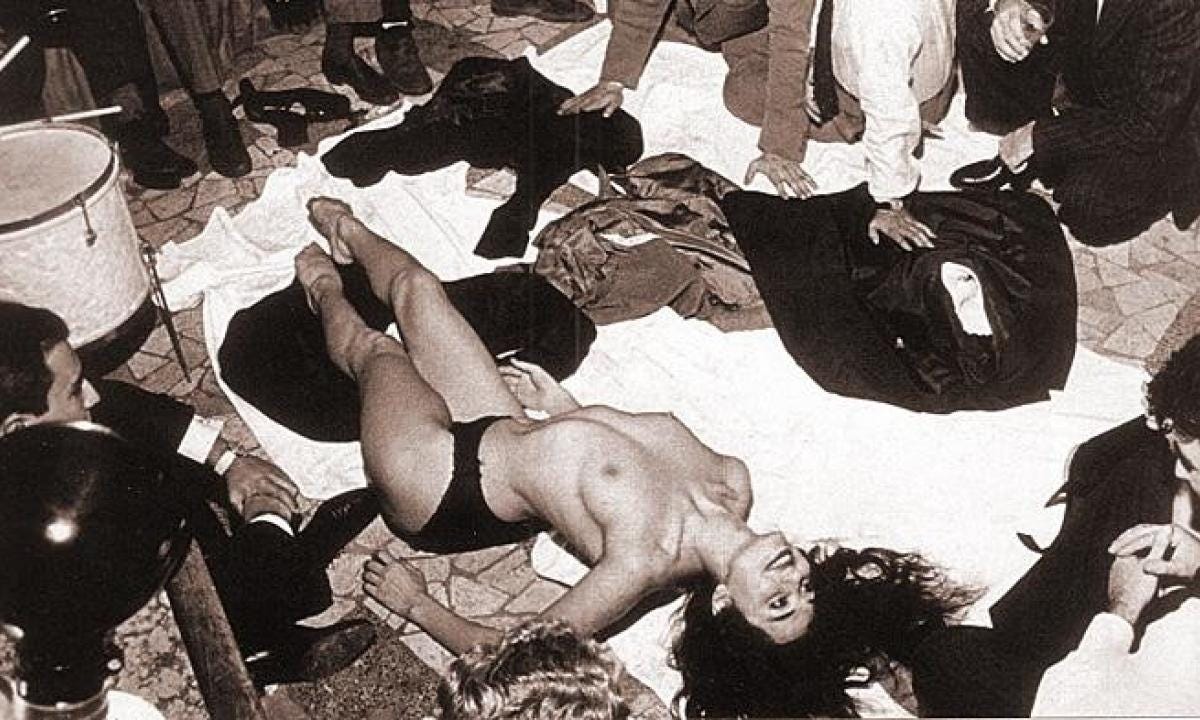

Nervously, Aiché had one drink, and then another. At her trial two years later, she claimed, “They drugged me, they made me drink a lot, and a sort of euphoric frenzy invaded me," but in photos taken of what followed, Aiché doesn’t look drugged. She looks delighted. She looks like a woman who is getting exactly what she wants, which is the attention and desire of every man and the tense disapproval of every woman. She’d trained as a belly dancer. Dancing seductively came naturally to her. That night, she let it rip.

Whether Aiché intended to pull off the publicity stunt of the century all along or just fell into it, no one knows. At some point, she slipped off her heels, her dress, petticoat, and bra, and she began to dance. It was the first time such a thing had happened at a private party in a public place. The Countess Olghina was not happy, but a lot of men were.

The show went on for about half an hour. Someone called the police. Italy in the fifties was still in thrall to the Vatican. It was a deeply Catholic country that had yet to see its airways flooded with schlocky, boob-filled, Berlusconi-era television programming. No one had witnessed such a display before, and Aiché earned herself a different kind of immortality that night when she was later mentioned in Federico Fellini’s famous film, La Dolce Vita.

Paparazzo Tazio Secchiaroli, who’d been burning up his camera taking photos, was among the first to see the police arriving. He found his friend, press agent Lucherini, ripped the film rolls out of his camera and stuffed them in Lucherini’s pocket. “You’re in a tuxedo,” Secchiaroli told him. “No one will stop you. Wait for me in front of the Royal cinema.”

Sure enough, Secchiaroli was stopped along with the other photographers, but had nothing for the police to confiscate. He rendezvoused with Lucherini in front of the Royal cinema, got his film rolls, and brought them to newspaper L’Espresso. Their publication created a furor that impacted the lives of everyone involved, especially Aiché Nanà and of all unlikely souls, jazz pianist Umberto Cesari.

There is no way to overstate the horror and collective pearl clutching that ensued. “Squalid story, squalid protagonists,” current events magazine Epoca huffed. “The deplorable scandal of Rugantino can be traced back to the sad mania for publicity that has now pervaded all environments,” tsk tsked gossip rag Oggi. Poor Aiché spent two months in jail before she was run out of town. She also lost a role in a Vittorio de Sica film. A few years later, she staged her own redemption tour, confessing her intention of converting to Catholicism. Wrapped in a mink stole with a scarf draped demurely over her head, Aiché tried to look as penitent and Mary Magdalene-like as possible in a series of very staged photos. It must have worked because she went on to participate in about a dozen films, including a truly awful 1979 sexploitation film called Images in a Convent where she played a lusty Mother Superior.

At the 49 second mark of this video, you will see Aiché make an appearance at a train station. For a variety of reasons, it’s hard to look at. Not because she’s unattractive, but because she wears her fear, desperation, and need so openly.

But for a godly and upstanding man like jazz pianist Umberto Cesari, things were not so straightforward. The torrent of bad publicity drove him out of the public eye. He immediately retired, becoming so paranoid, he rarely left the house. There were nights when Umberto, clad only in T-shirt, bathrobe and bedroom slippers, drank more than what was good for him. He sometimes wandered the courtyard of his building, and forgetting which door buzzer was his, leaned on all of them at once, babbling incoherently into the intercom. The career of this brilliant musician, considered one of the greatest jazz pianists in Europe, the Italian heir to Art Tatum, was cut short by his association with an event over which he had no control—an event that a mere twenty years later, no one would even bat an eye at.

Umberto died in Rome in 1992. He was 72. Aiché Nanà, also in Rome, lost a battle with cancer in 2014 at the age of 78.

Time goes on. Things change. But for that brief instant on November 5, 1958, Aiché Nanà pushed back on the finger-wagging prudery of post-war Rome. Her motives may have been murky—or openly self-serving. But you can bet that was a party that no one in Italy ever forgot.

I want to hear your thoughts! Be sure to leave your comments below.

Copyright © 2022 Stacey Eskelin

What a delightful "bad ass" free spirit Aiché Nanà must have been! Fabulous story with a sad ending. Once again, men judging women by so called "morals and values" that they never apply to themselves.

Great story Stacey! Sad...