The Most Italian Thing You've Never Heard Of: Fotoromanzi

Beautiful people posed like department store mannequins and dramatically subtitled equals big business

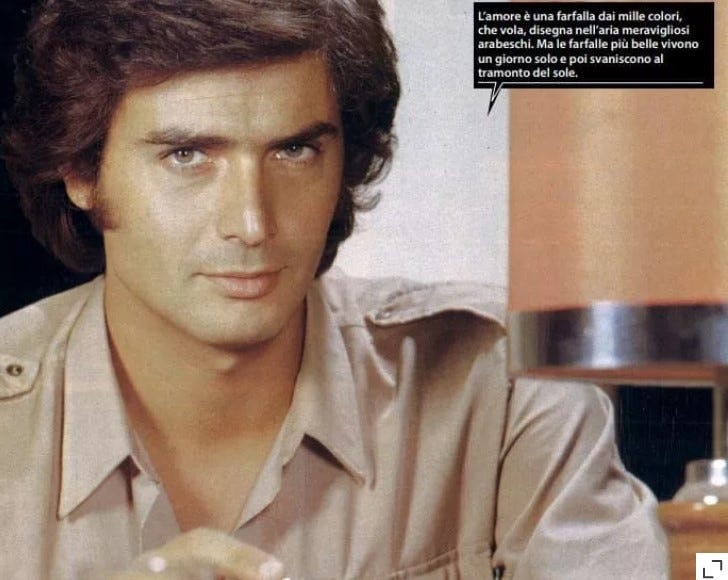

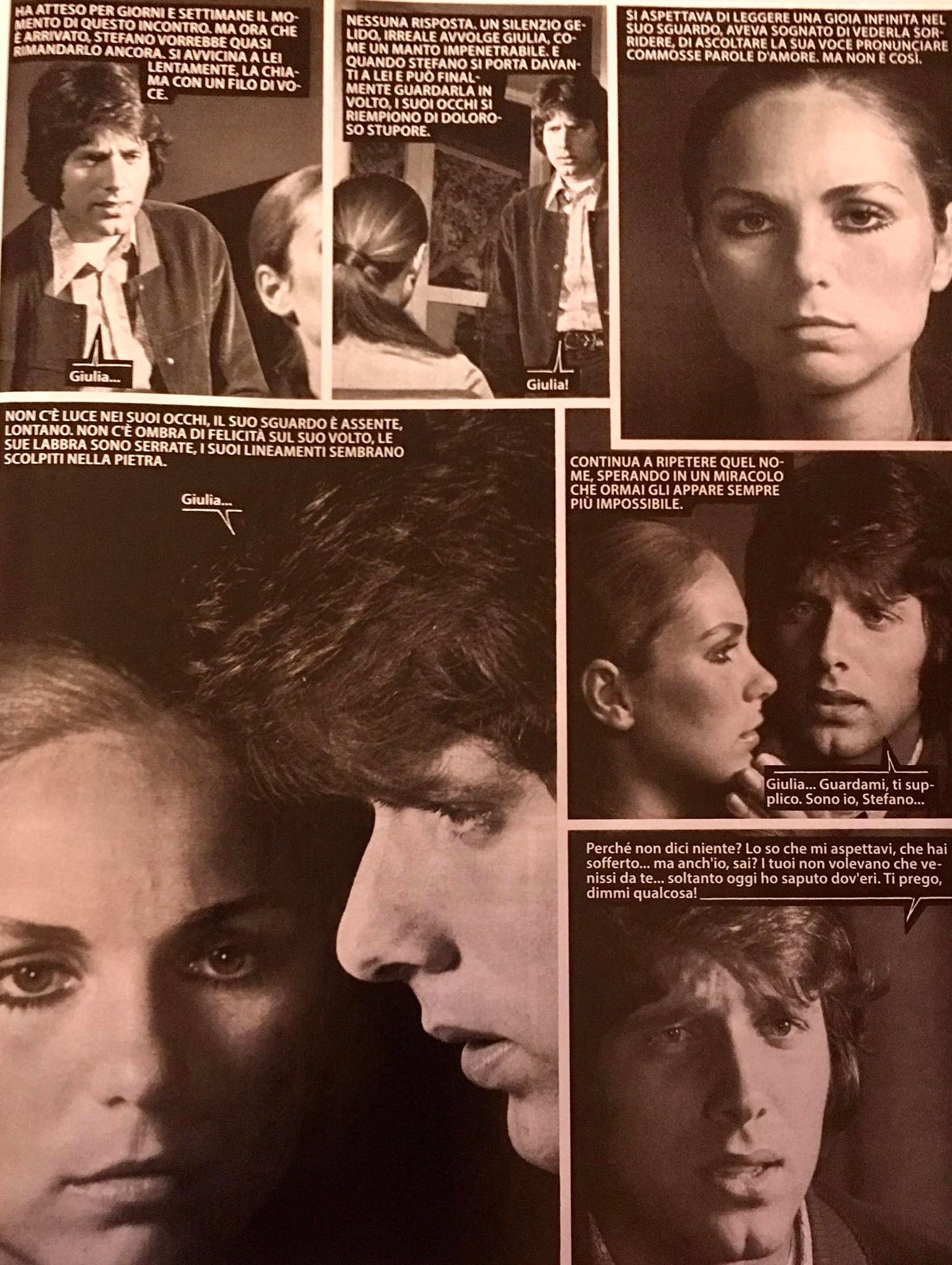

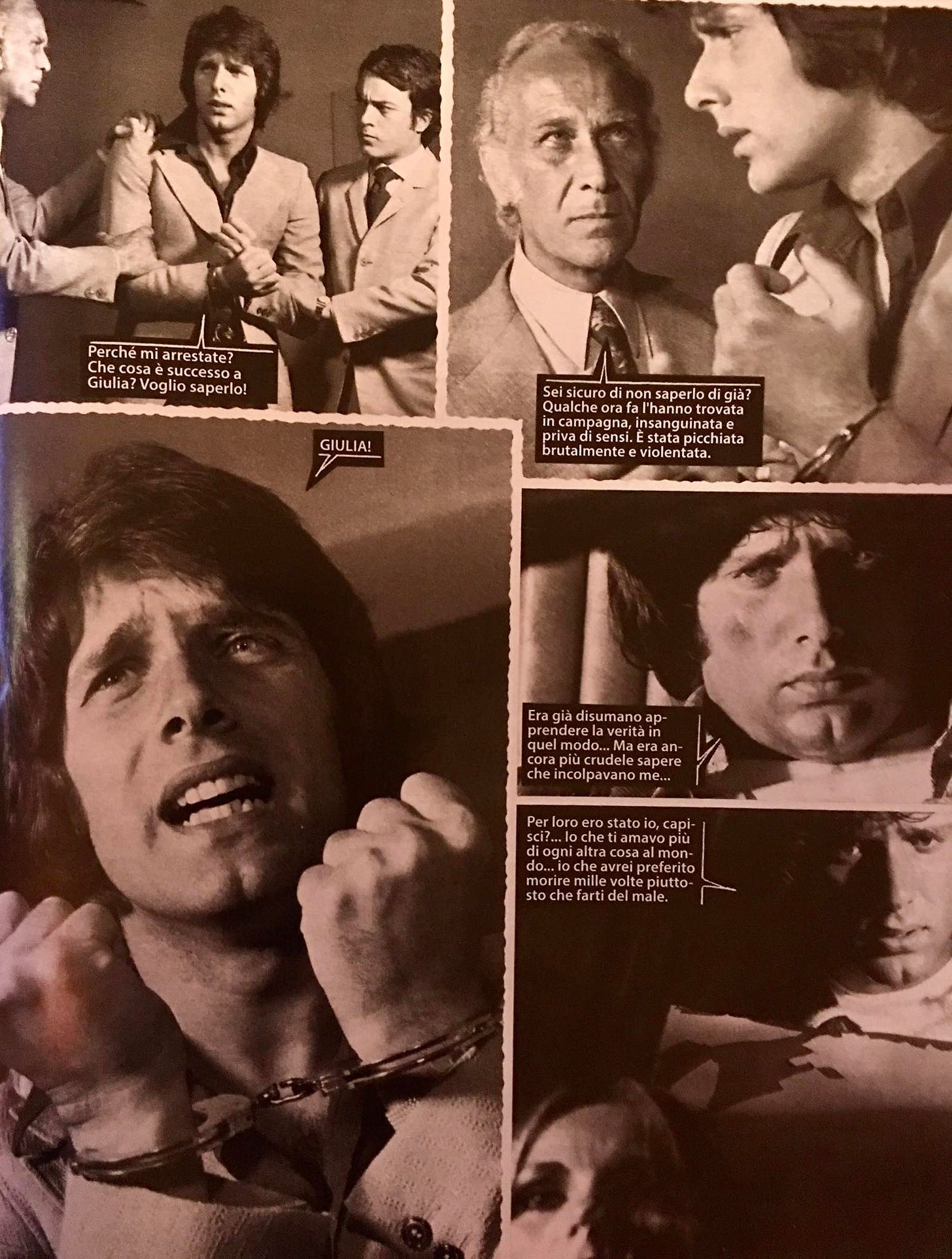

The first time I saw an Italian fotoromanzo or “photo novel,” I was sitting inside a doctor’s office in Civita Castellana waiting for John to fill out some intake forms. In front of me was a coffee table strewn with faded, thumb-worn magazines, all in Italian. One in particular caught my eye: stagey photographs of people in various stages of sexy brooding, each photo embellished with speech bubbles and text.

I was instantly and rabidly curious.

What I’d stumbled across is something so deeply and profoundly Italian, I will never be able to do it proper justice or even fully understand it, except to say that with an outsider’s (admittedly clueless) perspective, I’ll try to convey what fotoromanzi meant to Italian women, and also why I find them so fascinating.

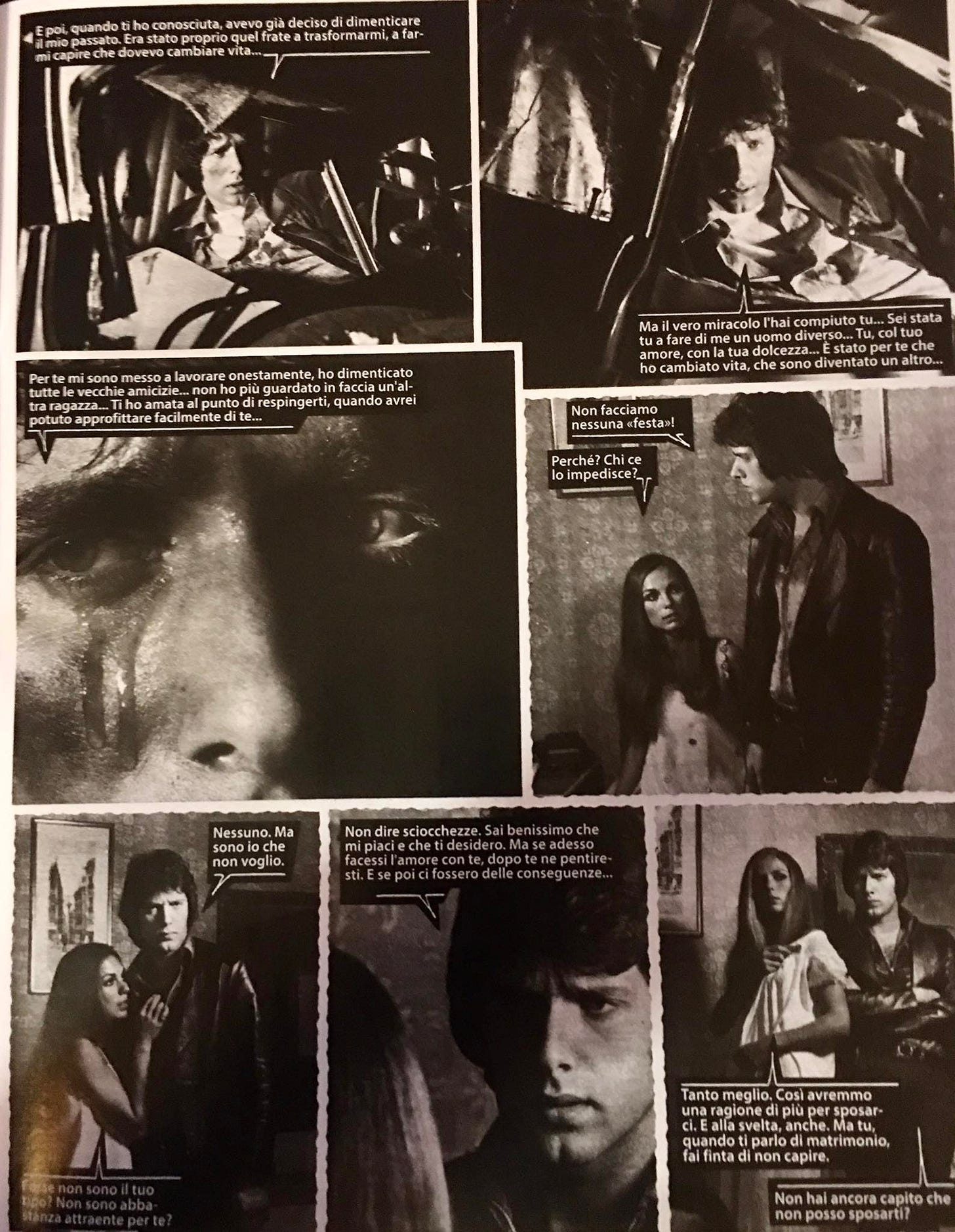

First, an explanation of what they are. Wikipedia defines fotoromanzi (foto + romanzi or “novels”) as a form of sequential storytelling using photographs, narrative text, and word balloons containing dialogue. Italy is said to have conceived the genre in the 1940s, expanded it in the fifties, where it also caught fire in Latin America. In the States, the fotoromanzo model of storytelling never gained much of a foothold, although starting in the 1970s, National Lampoon magazine ran a nudie feature called “Foto Funnies” that used a similar concept.

In Italy, however, magazines like Sogno (Dream) and Grand Hotel that specialized in the genre were meant to appeal to women, in particular working-class women. From the late forties to the seventies and even eighties, the publisher Lancio and others churned out storylines featuring stunningly beautiful actors, including Italy’s most famous export, Sophia Loren.

In 1976 alone, on average, 8,600,000 copies were sold each month, which shows how much economic clout fotoromanzi wielded, but also their profound cultural influence on generations of women. Storylines tended toward the simplistic: the rich are evil, the poor are good, good is rewarded, and love is betrayed. This ethos led to some marvelous story titles: "I Am Here, But You Don’t Know It", "I Love A Butterfly Hunter”, and "The Tale of the Bad Man".

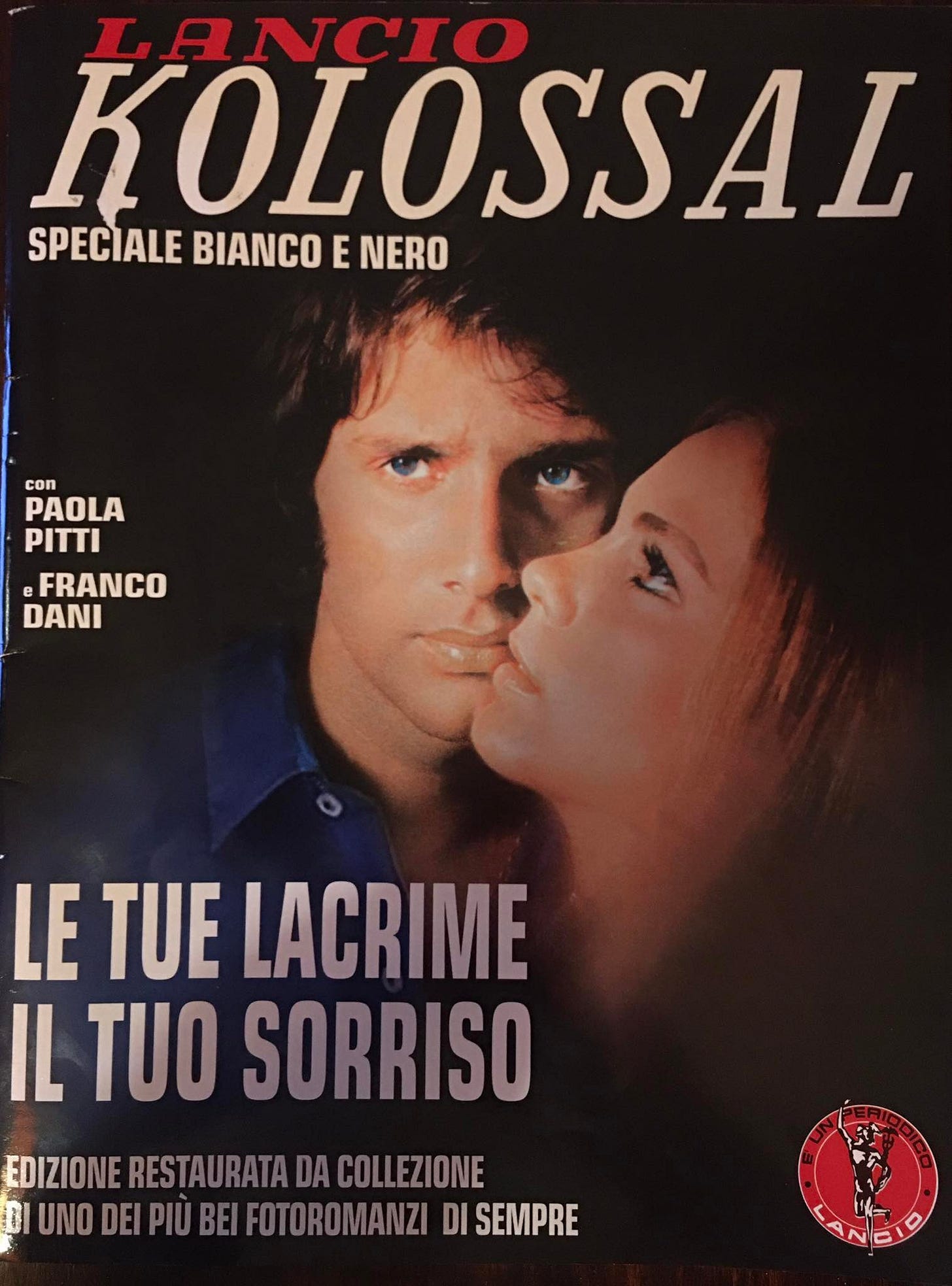

In 2020, perhaps in response to the boredom of lockdown, reissues of Sogno appeared on newsstands. This is how I managed to find one of my most prized possessions, a reissue of Lancio’s Kolossal, circa 1971, featuring two sirens of the era: the gorgeous, Yvette-Mimieaux-like Paola Pitti and Mr. Chin Dimple himself, Franco Dani, starring in Le Tue Lacrime, Il Tuo Sorriso, “Your Tears, Your Smile.”

Back then, Franco Dani was just another cleft-chinned, devilishly handsome fotoromanzo actor, but in the eighties, he became a huge Italian pop star, crooning such hits as, Ballando, Mio Amor (Dancing, My Love) and Fammi Toccare il Cielo (Let Me Touch the Sky) and the uber-hokey Quanto Sei Sexy, (Oh, How Sexy You Are) which I have kindly included here for you, my Cappuccini, and no, don’t thank me all at once.

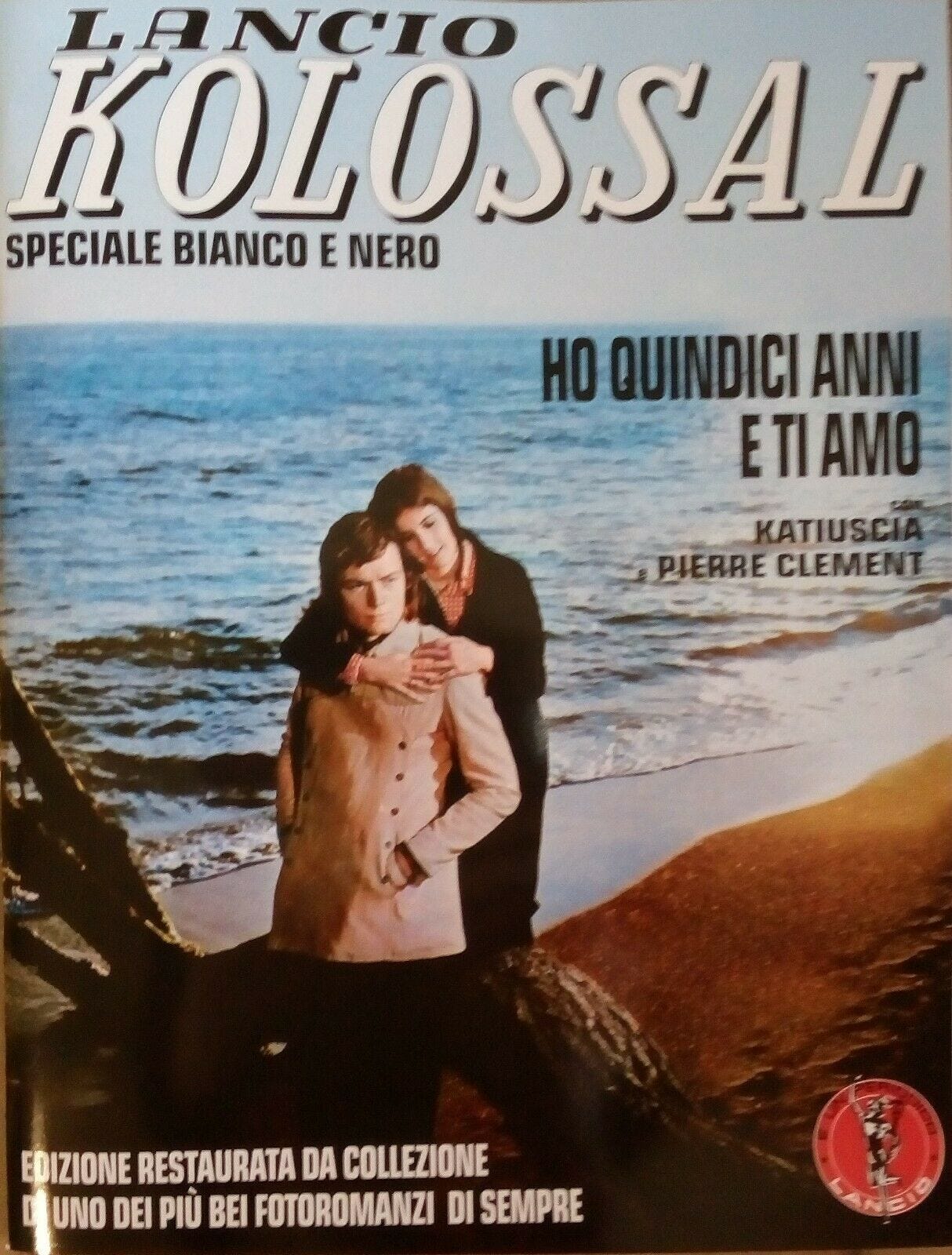

One of the tradition’s most popular faces belonged to Katiuscia Piretti, whose sister, Paola Pitti, and brother, Tony, were all fotoromanzi actors. Her first starring role, “I’m Fifteen and I Love You,” was scarcely concealed hebephilia, in this writer’s opinion, and may or may not have contributed to her later descent into hard drug use.

But the characters she portrayed inside the covers of a fotoromanzo were important to Italian women of the time, in large part because by the seventies, the depiction of female protagonists was slowly improving. Instead of the “simple girl in love” trope, Katiuscia’s characters were defying conventions and competing with men at their own level. They were courageous, independent, aware, and most of all, equal. Working class Italian women followed these stories like their lives depended on it. In a way, perhaps they did.

Of course, like most things female-centric, fotoromanzi were largely met with sneering disregard by the same people who now collect them as an investment vehicle. I’m obsessed with them because, to me, they feel so quintessentially Italian, so full of beautiful suffering. Every culture has its leitmotifs—America’s is the pretty, manic, pixie girl who leads a male protagonist to his doom or his awakening. Italy’s is not unlike its paintings of the Madonna: a lushly sensuous woman gazing tragically into the distance. You see it everywhere, from fotoromanzi to album covers.

Despite sexist prejudices, the fotoromanzo has been moderately successful at staging its “reunion tour” these past two years, even if it’s failed to engage new audiences. I’m reminded of the fact that at the height of their popularity from the fifties to the seventies, most Italian households still lacked a television. For important soccer matches, say, everyone met at the local coffee bar where a small, rabbit-eared box sat in one corner. There were only two channels at the time: Rai Uno and Rai Due. So, aside from books, there was no other way for an Italian woman to consume good, soapy, “it could happen to you” stories. Now, of course, there are a hundred ways, most recently TikTok.

Knowing what I know about Italian culture, I suspect there was a lot of yelling on those sets. A lot of yelling, espresso, cigarettes, and sexual harassment.

Perhaps that was the reason for all those beautiful tragedy masks?

What are your thoughts? I’d love to hear them. Please leave your comments below!

My first impression was that they were similar to American comic books...only with more cigarettes and sexual undertones.

It occurred to me too late that by clicking on that song, YouTube will now use that information to suggest music to me. Damn you, Eskelin!

One comparison that came to mind was with graphic novels, which are basically comic book issues that are bundled together to form a complete story line. The idea of treating these as a serious art form is a fairly recent development, outside the core group of dedicated aficionados at least.

Do you think any of the FR publications ever made a serious attempt at being art?

Also -- "Sogno". Is that Italian for "dream"? I ask because Christopher Tin composed this beautiful, rapturous little piece of music Sogno di Volare ("The Dream of Flight"). I post the link below. If you listen to this -- if for no other reason than to flush out that song above -- keep reminding yourself that this was composed for a f*cking VIDEO GAME!) It goes toward raising the question of "what is art"? The music to movies (and video games; I can't get over that) has become the classical symphonic music of our age. Yet many would dis the idea that it qualifies as anything other than pop tripe.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WQYN2P3E06s