The Ghosts of the Past Never Go Away

And all that's left are your scars, your love, and your cheap dollar-store tiara

“We call them survivors, but once the vampires get you, the person you were dies, like any traumatized part of you never leaves that room, that car, that moment, and you walk forward a ghost of your former self. You rebuild yourself over the years, but the person you were isn’t the person you become. The great bad thing happens, and you become a ghost in your own life, and then you become flesh and blood and remake your life, but the ghosts of what happened don’t go away completely. They wait for you in low moments, and then they wail at you, shaking their chains in your face and trying to strangle you with them.”

― Laurell K. Hamilton, Affliction

On my first full day in Houston, my son, Dane, took me on a “retrospective tour” of my former city. We drove around in his enormous truck and looked at places we used to live, neighborhoods we used to haunt, and public buildings we used to frequent.

But the past is full of ghosts. Moving 9,000 miles away is a convenient way to escape them. Yet, on that day, those ghosts were so close, I could scarcely breathe.

These years in Europe have softened my edges. I don’t wear armor anymore. Or makeup, for that matter. In some respects, I feel like a copy of a copy of my former self, a portrait done in watercolors or a sepia tint. The woman I was then, the values I held, the people I knew, the whirring hamster wheel of my life as a single mom, all of these memories came rushing back.

Some of the memories were unspeakably painful. We just happened past the movie theater where I somehow found the courage to tell Dane, nine at the time, that his dad and I were separating. The guilt I felt—and still feel—will likely never leave me.

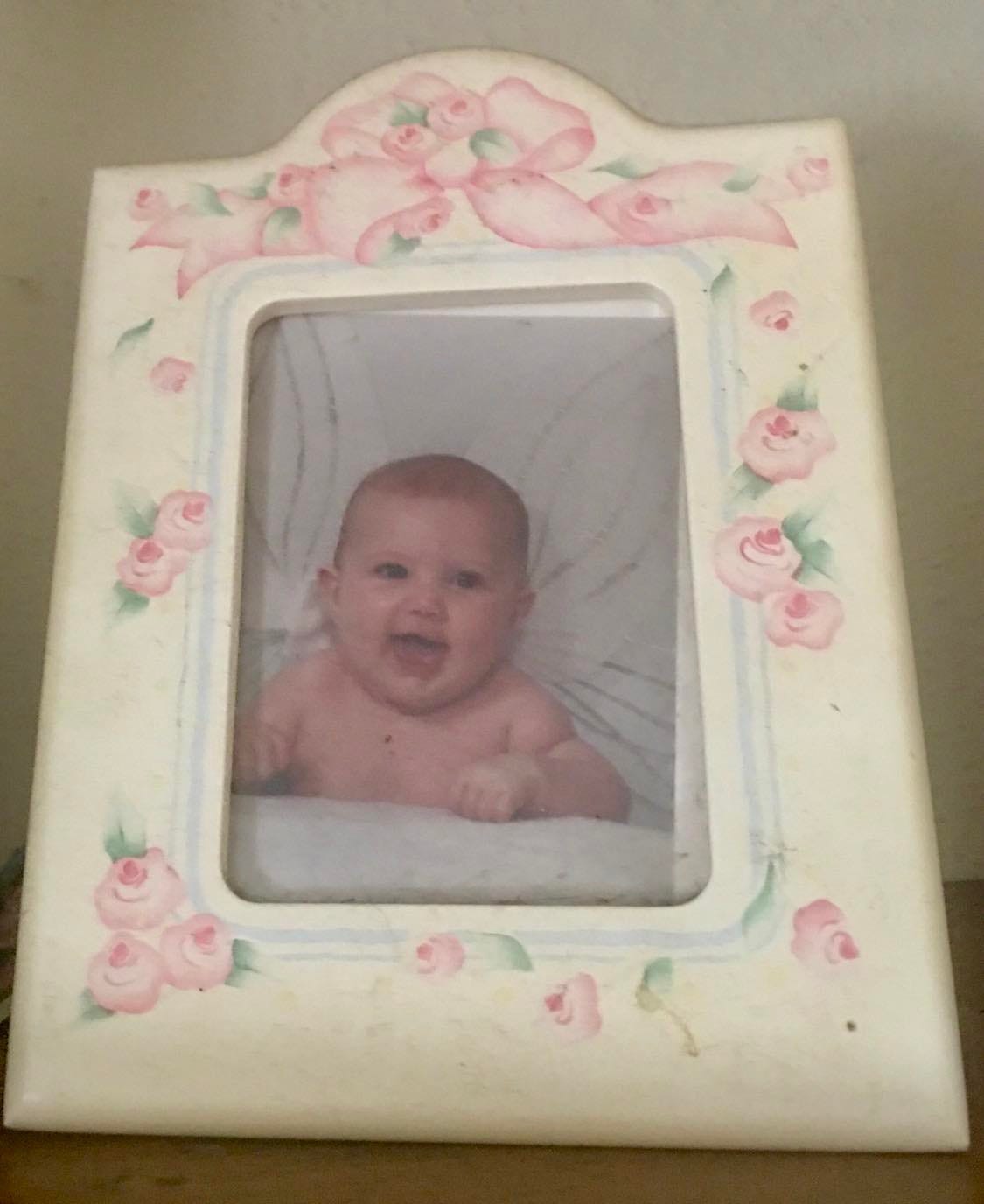

In my experience as a parent, I can with one-hundred-percent certainty say that I love my children equally, but they do evoke different emotions. My daughter, Kate, is my joy; Dane, my tenderness. On that day in 2005, I had to plunge a knife into that tenderness. I had to gut it. This beautiful child they pulled from my body and put to my breast, this son I promised so faithfully that I would never let anything bad happen to, only now I was the one delivering the blow.

We drove past our old house in Bear Creek. It has changed owners several times since it got swallowed up in the divorce. The front deck we built is still there, but the fascia is blue now. There’s a pool in the back yard, and all of the neighborhood kids used to come over to swim. Those days were so long, one endless summer, but somehow the years flew, and looking at them now through a glass, darkly, is surreal. I am reminded most acutely of the impermanence of all things. Most of my life is already behind me.

I lived in that house, raised my children in that house, and then we moved on. Here I am on this planet, and one day, I will disappear. Life is always in motion. It waits for no man. And even if you’re present for every second of it, there’s no way to hold on. Like a rip tide, you are pulled ineluctably forward, always forward, unless you have the masochism and the humility to look at the past.

The late, great Maya Angelou once said, “You do the best you can with the information you have at the time. When you know better, you do better.” But nothing prepares you for a full accounting of your own parental failures. Why can’t the unconditional love you bear your children be enough to wash away the sins? Despite your best intentions as a parent, you fail. It’s the most humbling feeling in the world. You have kids, sacrificing your time, sanity, body, your very life, for them. You promise yourself that you will never make the same mistakes your parents made (every generation does this), and maybe you even succeed. But what they don’t tell you is that you will end up making other mistakes, different ones, without even meaning to. It’s the nature of the paradigm. If all systems tend toward chaos, then all parenting tends toward failure, at least when you compare what you wanted for your kids with what you actually ended up giving them.

When Dane was a baby, I—in all my fiery determination to protect him from pesticides and chemicals—used to feed him expensive organic baby food. One day, I screwed open the jar and found shards of glass in his puree. Thank heaven I didn’t give it to him first. But as a writer trained to think in metaphors, I can’t help but the see obvious one there, which is this. Despite all our attempts to protect our children, life will have its way with them. The bully at school, the online taunting, the sociopathic teacher, the groping hand—you can’t be there every minute. You must send them out in to the world, even knowing that the world can—and will—do grotesque and irreversible damage.

You see your own past selves reflected in your children. Their constant and oppressive need for money. Their urgency to mate. Their cluelessness in the face of a society that expects them to fritter away their youth doing shit jobs for shit wages. You see the armor you’ve discarded taken up and worn defiantly by your own daughter, a necessary defensive structure for any young woman in Texas. You see their vulnerability, their flashes of brilliance, their nihilism, their addictions. And all you want to do is make it better, to protect them, only you can’t. You literally can’t. More importantly, you shouldn’t. Because it’s their dance now, and all you can do as a parent is watch them anxiously from the sidelines.

Hand to God, it’s the letting go that will kill you. The sovereignty you once held in your children’s lives is over. Here then is yet another reminder of your own impermanence. They will always be the most important people in your life, but with each year that passes, you move further down the rungs of theirs.

Some wounds never heal. You just grow used to them.

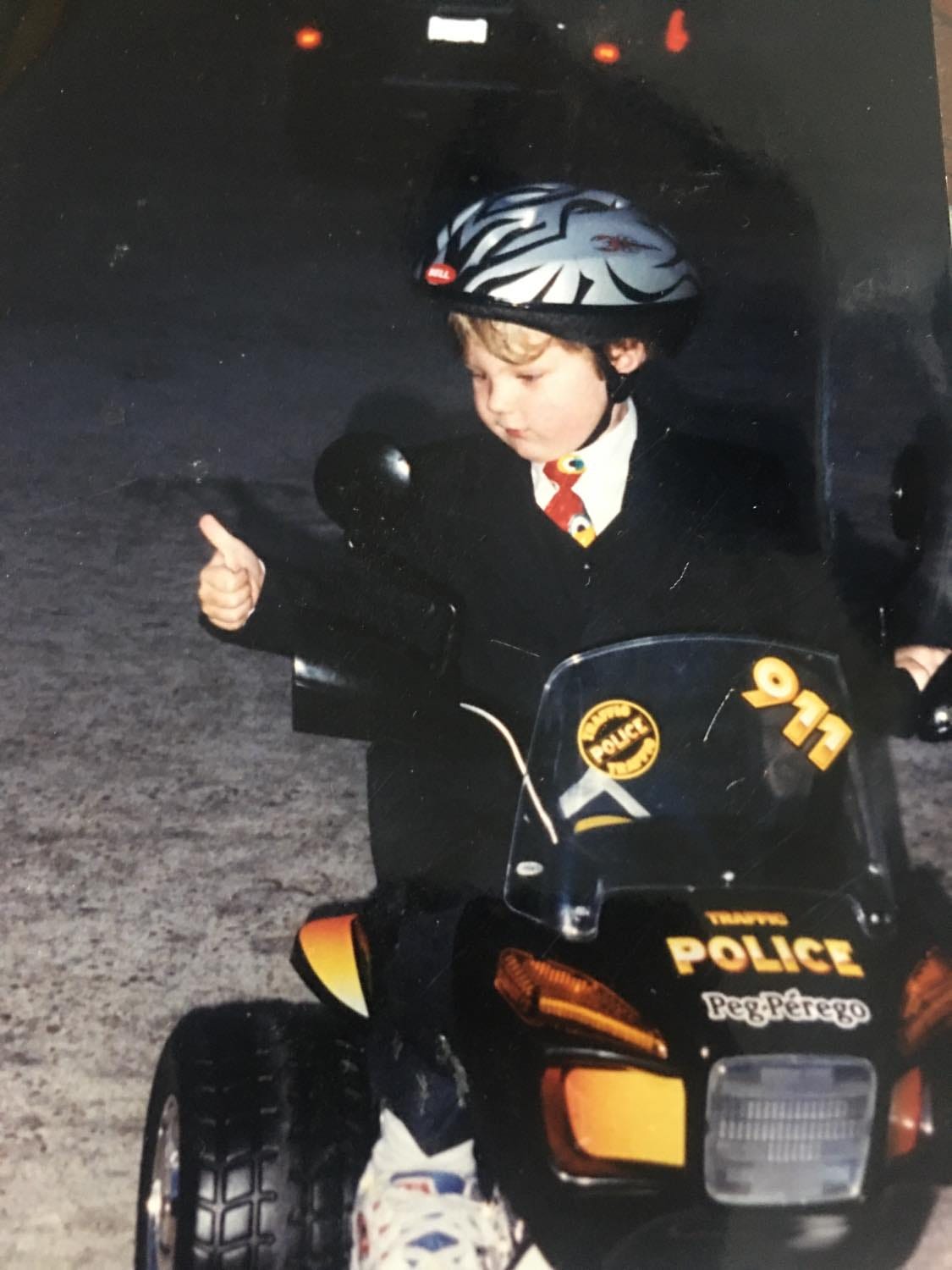

That day in Dane’s truck, we drove through Bear Creek Park, and I could feel those ghosts pressing in on me. There by the pond, Dane was still three years old, warily feeding the geese. Over there, an older Dane learned to ride a two-wheeler, his dad and I running after him, shouting encouragement.

A deer named Mr. Buck used to live inside a fenced-in area at the park, and when Kate and I visited, he’d fearless come up to investigate, letting me pet the velvety fur on his antlers. Sometimes, he’d just gently lick the salt off my hands and arms, his soft dark eyes mere inches from my own. Then one day, a twenty-three-year old man named Brandon Eugene Gregory brutally murdered Mr. Buck. He chopped him up and stuffed him inside a freezer. My children would come to the park to see Mr. Buck, but he was gone, and I had no words to explain to my children how some people were capable of such things.

And this is the world I have thrust them into, a world where all atrocities are possible, where the very impermanence of the things and people we love is its own atrocity. If I thought they’d understand, I’d tell them how my love for them is strong enough to pierce dimensional walls, how there is no love without pain. It’s a package deal. You don’t get one without the other. My love for them is the most important thing I’ve ever done. I am incredibly lucky to know it.

But it is up to them to discover this secret to life: We aren’t here to love ourselves. We are here to love others. For only in that love will we finally understand the truth. Power, achievement, striving, conquering are nothing, a void.

That void can only be filled with one thing, and that thing is love.

I am eager to hear your thoughts—from both parents and non-parents. Please leave them in the comments section below.

You can only show them the capacity to love. They have to learn to love in their own unique way. It seems that you've taught them well. Despite your penchant for being human and making mistakes, your children seem to have landed on their feet. I can't imagine how difficult that must have been. I never had the courage to do it myself.