The Fine Art of Sitting Outside in Perfect Weather Drinking Coffee

Europe knows how to do it; America, not so much.

I came to coffee relatively late in life, and even then, I did it all wrong. Previous to my injavanation (see what I did there, coining a whole new word?), I drank copious amounts of Diet Coke with artificial lime flavoring. For breakfast.

You can only do that when you have a young stomach. Now, it would be like swallowing napalm.

American coffee is hot and bitter—like a lot of relationships, I suppose—which is why I had to add enough milk and sugar to turn mine into breakfast cereal. Being American, and female, I decided that milk and sugar were unnecessary calories, so I dumped multiple packets of Splenda and powdered creamer into my brew, which I can assure you were not only just as many calories, they likely qualified as rat poison.

Have you read the label on powdered creamer? No one should be drinking that.

By any means necessary, I would find a way of conveying caffeine into my system, and not once did I stop to consider the idea that maybe, just maybe, American coffee (Starbucks, I’m looking right at you) is so brutally harsh, I was overcorrecting a preexisting problem.

I’d still be lost down that rabbit hole if I hadn’t moved to Italy where coffee is not bitter, not scalding, not acidic, and not $7.00-$10.00 a cup. It’s about a 1.10€ ($1.15). There is one size, not three; real dairy, not creamer; machine-made, not brewed.

I don’t even use sugar anymore. I don’t have to.

But it’s the way in which Europeans, especially Italians, take their coffee that sets them apart. They have a long storied tradition of sitting in charming outdoor cafés, sipping lattes, espressos, cappuccinos, caffè lungos, caffè strettos—or starting around 6PM, aperitivo, a pre-meal, mildly alcoholic drink meant to “open” the stomach before dinner.

Doing coffee the Italian way means stretching your legs and (depending on the level of conversation) your mind. You take in the view (here in Italy, the view is almost always spectacular). You run into friends. You people watch. The whole experience leaves you feeling emotionally energized, not so jacked up you can smell colors.

Let’s compare this with how we do coffee in the States.

Some cities have outdoor, café-style seating, but not most. Starbucks tried “translating” the Italian tradition of coffee into American consumer English, but by Italian standards, it was an epic fail. Too many Starbucks’ patios overlook a parking lot. More than 70% of the chain’s business comes from drive-thru or mobile orders.

Most significantly, the manner in which coffee is consumed in the U.S. differs dramatically from the way it is consumed in Europe. Here, coffee is meant to be savored whilst in the company of good friends. In the U.S., we pound it like mindless apes in order to quickly achieve its effect. Then it’s off to the next meeting, the next errand, the next playdate for the kids, only now with a little more pep in our step.

Well, until the inevitable insulin crash happens twenty minutes later.

But no worries, there’s another Starbucks.

Being forced to spend 24/7 on the capitalist rat wheel (now more than ever) means Americans don’t have time for leisurely coffee. We’re not in it for the enjoyment; we’re in it for the punch. That same mindset compels us to work ourselves to death and pretend it’s a virtue. Perpetual busyness has a certain cachet. We’re on our phones, we’re at the wheel, we’re on our way somewhere else, and oh, hey, I’d like a Venti Caramel Ribbon Crunch Frappuccino with twelve pumps of vanilla ***peers suspiciously inside drive-thru window to make sure it’s the full twelve***.

Even if we had outdoor cafés that weren’t next to freeways, even if we had drinkable, affordable coffee, even if we had friends we actually liked hanging out with, what we Americans don’t have is time.

None of this is our fault, but it is our problem, and it’s one that shows a flaw in the system. Everyone should have time to meet friends for coffee. We shouldn’t have to drive twenty miles to get there. And the coffee should be good, affordable, and not part of a chain. If we have kids, there should be a park where we can watch them play whilst sitting at a table talking with our grownup friends—and perhaps most importantly, avoiding our phones.

You get how this is doable, right?

Deep down, Americans believe that abstract concepts like “beauty” and “quality of life” are things they can’t afford. And maybe that’s true. In our present system of fifty-hour work weeks, cost-prohibitive childcare, decaying suburbs, and almost zero social safety net, it’s hard to conceive of a better life, especially when it takes every ounce of strength we have just to keep our heads above water.

But when we think about creating our best life, we tend to think in grand, sweeping terms, in overhaul: a new house, a new spouse, a new city. I’m suggesting we start small. I’m suggesting we start with coffee.

For over 400 years in Europe, cafés and al fresco dining have brought people together and nurtured a creative, artistic environment. They sprang up before the advent of television and cell phones and were essential for the dissemination of ideas. Many Europeans don’t have backyards, which is why cafés have always served such an important function.

Curious, isn’t it, how American suburban houses are “moated” by big yards where no one plays and nothing happens, and how we’ve driven ourselves indoors with air conditioning? We’re exhausted by the end of the day. All we want to do is hide. Oddly, it’s the worst thing for the psychological health we keep trying to claw back. Like it or not, we are community fish. I spent a lifetime trying to prove to myself that wasn’t true.

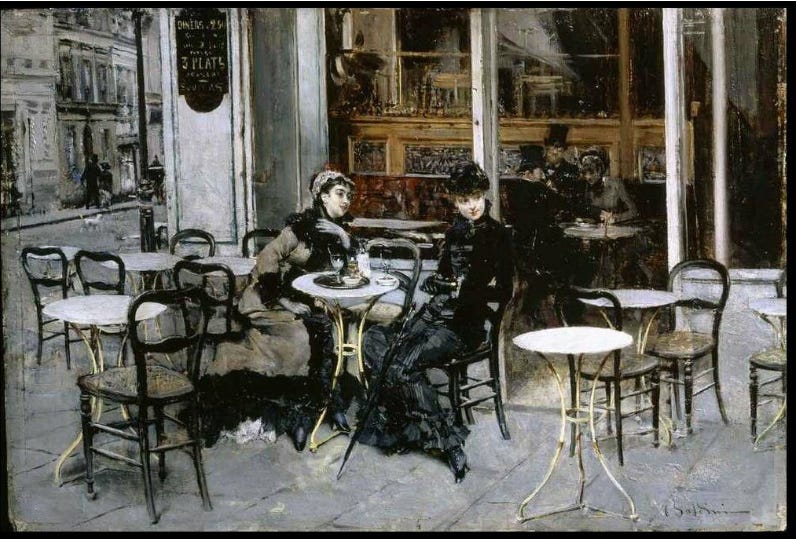

So, for purposes of inspiration, beauty, and community fish, I give you a fine arts retrospective. May America revive a beautiful and necessary tradition.

What are your thoughts on the importance of best-life goals and aspirations? I’d like to hear them. Please leave your comments below.

Copyright © 2022 Stacey Eskelin

This is one of the reasons I came to hate Houston- that feeling of rush, rush, rush. Everyone has to be somewhere 30 minutes ago. The sound of the freeways are ever-present and the sound of cars zipping by at 60MPH (if it's not rush hour) doesn't support relaxation and quiet conversation. Most big cities are the same, but Houston takes it to new heights (or depths, depending).

I stopped drinking brewed coffee in the US, because it's uniformly shit. At home I drink tea, and when I'm out and about I'll have an oat milk latte. That gets my blood-caffeine level to a manageable point, and I'm not drinking something that tastes like my last relationship prior to meeting Erin.

One of the things I miss about living in the Middle East is Turkish coffee. It differs from country to country, but it's uniformly called "Turkish" coffee. I rarely have it anymore, because it's hard to find outside of Middle Eastern restaurants, but it does bring back a lot of memories.

In the 17th and 18th C. England -- during the days of Locke, of Newton, of Pope, of Hume (though he was admittedly Scottish) -- coffee houses were known as "penny universities" for the intensity of learned conversation that occurred in them. Actually (1) having some place to go that I could (2) afford to go to would be a great pleasure. But Johnston City doesn't even have sidewalks, never mind sidewalk cafes.

The time I went through Paris (vacay while working for an "Uncle") (maybe I should say "times," since I passed through twice, and lingered once) I loved the opportunity to just sit and order a cafe, and be happy with whatever arrived. One of those times I was with some folks I'd met traveling. It was quite late, and (I'm told) there was a kind of "courtesy" the French would do for students where they'd serve them espresso in a full sized coffee cup. I was 24+ hours vibrating like a "magic fingers" on speed balls. And back in those days I could gulp down a cup of coffee before going to bed and sleep like a baby. (A few years later my body chemistry shifted in some fundamental way, and as a result I've struggled with insomnia for the past 4 decades.)