Almost everything in Italy is old.

The palazzo we live in is from the 16th century; our frescoed ceilings from the 18th century. Right down the street, available for public viewing, is a stretch of the original Via Appia, the famous 130-mile stone road built during the time of Ancient Rome. Ten cisterns beneath our village of Amelia are from the 1st century.

Finding yourself surrounded by beautiful old things is a powerful reminder that your own human existence is nothing more than a blip on a continuum of human existences. Things survive; people do not. Someday in the not-too-distant future, I will pass into dust, the same dust as the millions that came before me.

In Italy, these are not just idle thoughts. Death sits implacably on your shoulder wherever you go. But there are even starker reminders that your number will soon be up, and by that I mean the Death Walls.

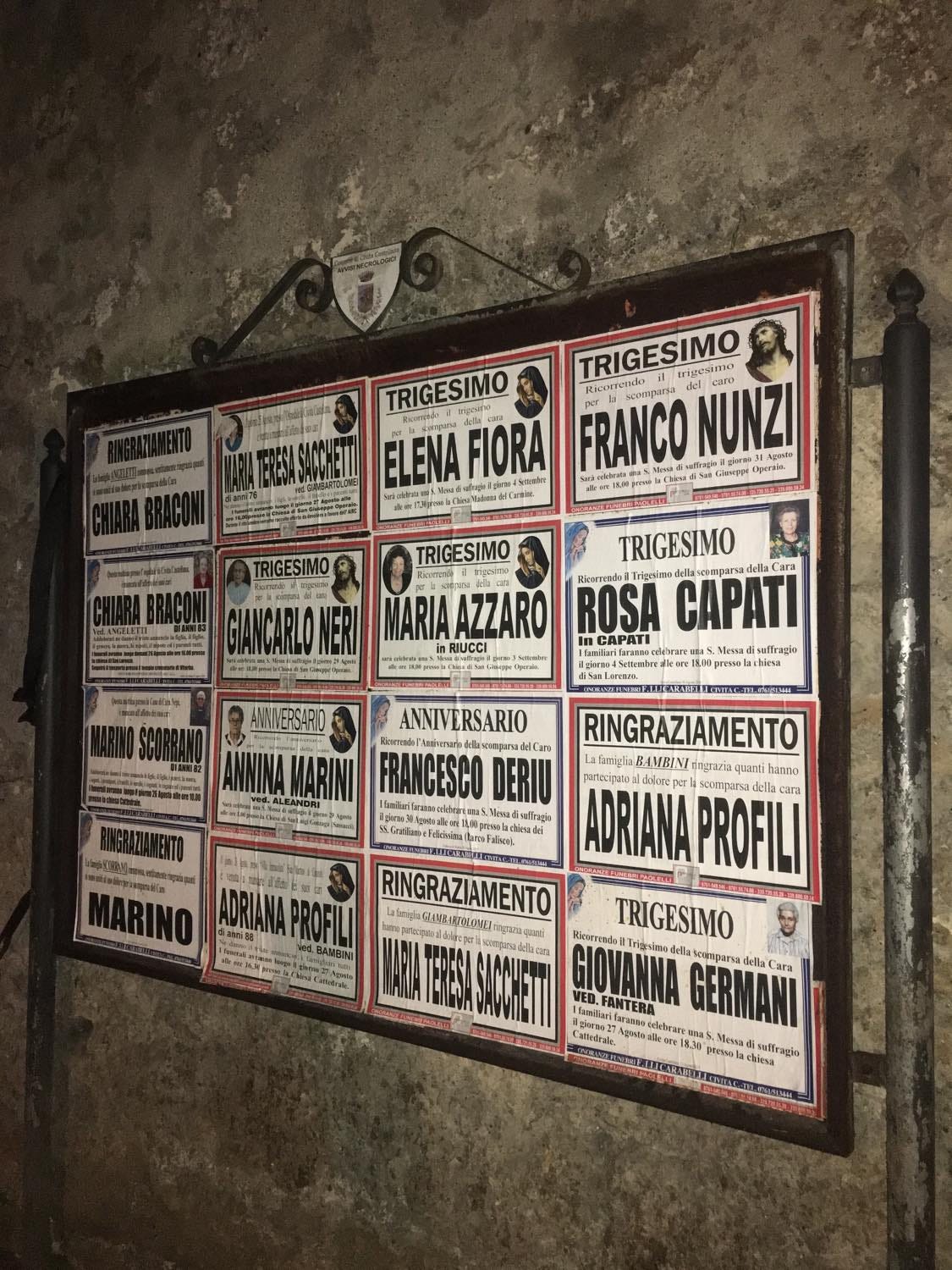

If you walk through any Italian village, eventually you will find an oxidized black metal board on two iron posts that has death notices papered across it. Some are fresh; others are peeling with age. They usually include a formal-looking photo of the deceased, something stiff and unsmiling, and the date, time and place of where the funeral will be held. This is because everyone is invited to the pay their final respects, a lovely Italian tradition that warms the cockles of my insular American heart.

I’ve been to American funerals that were attended by two or three people. It’s seriously depressing. Here in Italy, funerals are neighborhood affairs held in sumptuous Renaissance churches. They’ll highly ritualistic, like most Catholic traditions. And sometimes the dead are buried with a beloved object—a pack of cigarettes, a book, a rosary, a photo, with the idea that an unquiet spirit might return to earth and bedevil the living.

In days of yore, wealthy Italians would actually pay for mourners to cry and wail and beat their chests and rend some garments right at the gravesite, which is no small feat. Imagine being able to turn on the waterworks like that in a professional capacity. What if it was someone you hated, and all that came out were peals of laughter?

In keeping with a healthy acceptance of death and all that precedes it, renowned beauties like Sophia Loren are allowed to age in this country. Female news anchors are often over forty, sport a few wrinkles, and aren’t tricked out like blonde-in-a mini-dress Fox News show ponies. You have to ask yourself why. Italian entertainment can be wildly sexist—there are prime time variety programs on TV featuring topless dancers that never utter a word of dialogue—and yet so many actors and singers are beloved national icons aging in the public eye until their deaths.

I have to think this kind of fatalistic acceptance of aging and death stems from Italy’s daily relationship with and immersion in its own past. In America, we despise history, whether it’s a building or a woman’s face. No one is allowed to age in our country. Our obsession with looking young is nothing short of sociopathic. An American actress who looks her age isn’t revered and celebrated; she’s unemployable.

Which brings me back to Italy’s Death Walls. Is this why, when it comes to fashion, Italians seem to favor the color black? Why the first thing one Italian nonna will ask another on the phone is, “Did you hear who died?”

“Se vuoi essere disprezzato, sposati; se vuoi essere apprezzato, muori,” the Italians say. If you want to be despised, get married; if you want to be appreciated, die.”

What would you rather—newspaper obituaries or Death Walls? Comment below!

The comment about professional mourners reminded me (once again) of Harry Morgan's line to John Wayne in "The Shootist": "Books, the day they put you under, what I'll do on your grave won't pass for dancing."