Social Status. Do You Know Yours?

It's the dirtiest of dirty little secrets, but you ARE being judged every second of the day by almost everyone you know.

Now, the Star-Belly Sneetches

Had bellies with stars.

The Plain-Belly Sneetches

Had none upon thars.

Those stars weren't so big. They were really so small

You might think such a thing wouldn't matter at all.

But, because they had stars, all the Star-Belly Sneetches

Would brag, "We're the best kind of Sneetch on the beaches."

With their snoots in the air, they would sniff and they'd snort

“We'll have nothing to do with the Plain-Belly sort!"

And whenever they met some, when they were out walking,

They'd hike right on past them without even talking.

~ THE SNEETCHES by Dr. Seuss

As far as theories go, it is generally accepted that we humans are hardwired to experience two types of happiness: hedonic (pleasure and enjoyment) and eudaimonic (meaning and purpose). But recently, psychological science has identified a third, somewhat neglected aspect of what people consider a good life, which is psychological richness. A psychologically rich life is characterized by interesting and perspective-changing experiences.

And that’s me, right down to the bone.

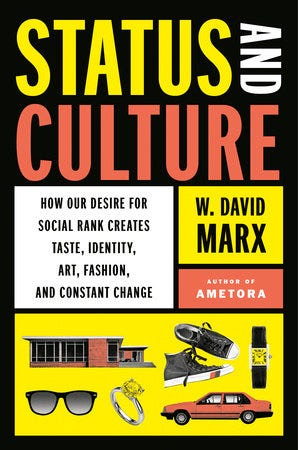

I’m almost a stereotype of the breed: rabidly curious, holistically thinking, and politically liberal. Something tells me you might be, too. After all, you’re reading Cappuccino, and like does attract like. So, when someone like us finds a book like Status and Culture: How Our Desire for Social Rank Creates Taste, Identity, Art, Fashion, and Constant Change by long-time culture writer W. David Marx, we immediately start plowing through the couch cushions to find enough money to buy the thing. Just try keeping something this juicy and psychologically insightful out of our sweaty little hands. Just try.

It’s a book that has already attracted the attention of Michelle Goldberg at The New York Times who wrote an op-ed about it titled “The Book That Explains Our Cultural Stagnation.” In it, she describes the book as “not at all boring,” and one that “subtly altered how I see the world.”

What’s amazing is that it has not only altered how I see the world, it has altered how I see me, which is always a little unsettling.

In Status and Culture, Marx advances the idea that artists innovate to gain status. Furthermore, consumers, who are no less concerned with their own status, publicize their cultural/artistic tastes and preferences as a form of advertisement for who they are, thereby adding or detracting from the status of the artist, trend, or fashion. In a way, it’s narcissism in its rawest form, a peacock competing for mates but in borrowed feathers.

Marketers make full use of this human predilection for identity consumerism. If you’re a woman, for example, who goes to a lot of Yoga classes, what does it say about you when you show up wearing expensive Lululemon tights versus Target-brand stretch wear? What social cues are you broadcasting? That you have money, yes, but also taste and discernment (or so the theory goes). A higher social status is automatically conferred upon you based on what you’re wearing. That goes double for your car, your zip code, your handbag, your shoes, what your husband does for a living, and what size diamond you have in your wedding band.

None of this is spoken, of course; merely understood. What blows my mind is that until reading this book, I, personally, have never grasped the massive implications of social status. It was sitting next to me this whole time, and I never recognized it. Oh, I could identify money, and how people who had it tended to look and act, but I never stopped to analyze the specific social cues they were emitting every second of the day. It’s an arcane language, these social cues, one I don’t know the first word of.

Reading this book, it felt as though I were seeing a flipchart of photos from my life when I actively rejected status, went out of my way to avoid it, found myself mystified by people who sought it, and failed to appreciate the importance of it.

To be clear, I see this as less of a virtue and more of a shortcoming. Status signaling (the active pursuit of status and/or trying to convince others that we have it) is a huge no-no in American culture (in Italian culture, less so; making a “bella figura,” or good show, is acceptable currency here), but I’m not implying that my ignorance of social status is principled. It isn’t. It’s more likely shortsighted and stupid.

So I found myself wondering how much of my inability to court status, seek it for myself, or even recognize it when it’s right in front of me stemmed from being a geek (geeks have no sense of hierarchy) or relentlessly middle-class. Then I realized that middle-class folks are often the most acutely aware of status. More so than the rich, at times.

Geek it is then!

I’m sure this drives friends who do understand social status a little crazy when they introduce me to people they know. What clueless, godawful thing will come out of my mouth next? But geeks tend to assign people to one of two camps: Cool. Not cool. No, we don’t know how much your handbag costs. We are just as happy shopping at Pay-Less as we are at Manolo Blahnik. Your car is awesome, but it doesn’t make us think better of you personally. We merely think you have a badass car.

Wealthy people buy expensive things to show that they can afford them; geeks buy not-so-expensive things because they can afford them. Unless, of course, they are rich geeks. Geek friendship is therefore disinterested and agenda-free, unless “agenda” means wanting to have an interesting, gut-level, perspective-changing conversation with you.

W. David Marx says in Status and Culture: “Status … is … an invisible force undergirding the entirety of individual behavior and social organization … And only when we become experts in status can we work to achieve the society and culture we desire … Everything we do, say, and own—or choose not to do, say, or own—becomes a sign [of status].”

You can understand my panic. How am I—and others like me—supposed to make ourselves want something (status) when we wouldn’t be able to identify it if it sat on our faces?

According to W. David Marx, it is the constant struggle among status groups that fuels the creation of new culture. In other words, cultural movements happen out of equal parts artistic vision and egoic striving for status, especially when a member of a subculture (e.g., Bebop, Art Deco, Abstract Expressionism) is trying to gain wider acceptance.

I find this to be particularly true of men, who have a long history of egoic striving for status. We women are rarely encouraged to strive, certainly not on behalf of ourselves. We can, however, strive vicariously through our families and marital alliances. In other words, we’re not allowed to wield power ourselves, but we can be power-adjacent. This explains why it is taking longer for us to exercise organized political clout (compared to the LGBTQ community, we are the rankest of amateurs) and at least partially explains why we haven’t always found ourselves at the vanguard of cultural movements—a misfortune that is compounded by odious amounts of sexism and/or a desire to clear the playing field.

If creating art is a form of social striving, and women are only encouraged to strive on behalf of our husbands and children, no wonder it is taking us a little longer to achieve. That, the forced reproduction of the past six million years, and the crippling misogyny of religion really stacked the deck against us.

This is slowly changing, of course, but not fast enough to save us from banality—otherwise known as the Internet—which is leading us into a cesspool of cultural stagnation. Herein lies the crux of Marx’ argument.

Per Marx, before the advent of the Internet, we relied on barriers of distribution to give things value, especially status value. If Cindy has something (a pair of destructed denim wash jeans, for example) that Robin doesn’t have, Robin is likely to want those jeans rather badly. The jeans are cool because they are exclusive. But when everything is available to everyone immediately at the press of a button, nothing is exclusive and therefore has little value. In this sense, according to Marx, the sheer democratization of the Internet, the fact that everyone is the star of his own YouTube channel, churning out amateur content and even becoming famous for it, has brought into relief a singular question: what’s cool anymore?

So, we look to Influencers to tell us what’s cool. If Kylie Jenner likes a brand of sneakers and makes them seem desirable and exclusive, you can bet millions of kids across the globe are going to buy those sneakers. By allying themselves with a beautiful young Influencer like Kylie Jenner, consumers are able to bask in her reflected glory, yes, but also broadcast something about themselves: I’m hip. I’m cool. I’m cutting edge. You can tell by the clothes I’m wearing.

Culture has finally reached its zenith by becoming one massive capitalist juggernaut.

What’s missing in all this mishigas is the idea that status chasing is a pitiful waste of time, money, and resources unless you know how to do it right. Status itself is rarely talked about because it’s that big a taboo. It’s our dirty little societal secret: we want to be cool. We want money. We want all the sex that being cool and having money provides.

But if status seeking in the artistic community is the only engine driving cultural and artistic innovation, and recognition is no longer available at the same scale, perhaps artists will learn to recalibrate their priorities and enjoy the labor instead of the fruits. In other words, maybe there’s another way to be an artist rather than always striving to come out on top.

But what do I know? I’m nothing but a non-status-jockeying female geek who assigns zero credit for wearing the “right” brands.

Trust me, I’m the first one who’s going to get sliced up into tiny pieces of human chum and thrown behind the boat.

Copyright © 2022 Stacey Eskelin

Pretty weighty, abstract subject matter, I know, but worth thinking about. Leave your thoughts in the comments section below. I’m eager to read them.

Yeah, we're all tribal...and we're all sheep. We like to think we're unique, and to a certain degree we are. But we all want what's "cool," and that means millions of us buying the same shoes, jeans, toothpaste, etc, ad infinitum, ad nauseam. I have to admit that I've never really though about it in the way Marx discusses it, though. All the times I've convinced myself I was unique and different, it turns out I really wasn't. Damn...that's kinda depressing.☺️

Now, you’d love “The Primates of Park Avenue”, a book written by an social anthropologist who lives in the Upper East Side!