Other Than That, Mrs. Lincoln, How Was The Play?

If Italy is a country of the soul, and Manhattan is a city of the mind, then Houston is the gut.

It’s been a minute since I’ve been able to sip, let alone write, a Cappuccino.

And as a general rule, I don’t like talking about myself, but there are a few things to know:

1. Once again, John and I have been geographically relocated.

2. There’s a lot less of me to relocate.

In October of last year, I underwent a very medically necessary breast reduction. After three bouts of pneumonia (apparently, twenty-five pounds of weight on your chest makes the bottom of your lungs a swampy, inhospitable place), it was easy for me to prove the “medically necessary” part to the good people at Medicaid. Less easy was the sheer number of MRIs, biopsies, doctors’ visits at cruelly early hours, ultrasounds, more biopsies, and various hospitalizations for said pneumonia.

It was a tricky surgery, due in part to mysterious fluid retention in my left breast. Some doctors flat-out told me they didn’t want to perform it. But like any organism fighting for its own survival, I persisted.

Uptown, crosstown, I trekked from one plastic surgeon to another in all weathers, my trusty backpack weighted to counterbalance the heft of my boobs (think: crippling back pain), fielding people’s stupid remarks, their accordion-eyed ogling, their covert photos. Some cultures are better about not doing stuff like that. New York City isn’t one of them. All I could think about was the day when I might feel some approximation of “normal.”

The surgery itself took about four hours. At six in the morning, I walked into the OR under my own steam, knees knocking, eyes as big as dinner plates. They leave the shiny sharp things in plain view. I hate shiny sharp things. The nurses strap your legs to the surgical table. After that, it’s lights out, a sleep like death. No dreams, no vague sense of self, no dim awareness of the passage of time. Under anesthesia, you cease to exist, and when you finally struggle up from that ether, it takes a while to Lego yourself back together again.

I had drains. Drains are no fun. John had to work, so I recovered for the first day or two in Midtown at my brother’s apartment. A kinder, more patient, more Zen soul you will never meet than my brother, who, along with his wonderful wife, took excellent care of me. Rarely have I felt more loved.

A week after my surgery, our lease was up in the East Village apartment, which was a blow. I wasn’t allowed to lift my arms, let alone heavy boxes, so John had to pack everything himself. Because I had follow-up appointments, we sheltered for a few more weeks in Williamsburg. Unfortunately, our Airbnb was eye-level with the BQE, an expressway, which was nearly close enough to touch. Because of the expressway’s position relative to the apartment, massive tractor-trailers continuously lanced our eyeballs with their high beams and went crashing over steel road-plates.

Five times I opened my laptop, intent on writing a Cappuccino. Five times I closed it because the constant mayhem made it impossible to think.

I hated that month.

I also hated the fact that after almost two years, we were being forced to leave New York, yet more refugees from a city housing crisis that shows no signs of abating. If two people working full-time jobs can’t afford rent in New York City, imagine what two freelance artists can’t afford. Since the pandemic, people like us are being heaved out with the garbage to places like Detroit, Baltimore—Houston—which is where we eventually landed. My lovely family is here. Less lovely is moving from an apartment in the East Village to one tiny bedroom in the Houston suburbs.

In a way, where I live doesn’t matter. Whether I’m in Bangkok, Thailand, or Bangor, Maine, I’m still at home in myself. But in other ways, the culture shock is jarring. Manhattan is real. In-your-face, up yours kind of real. You’re in constant contact with other ants on the mound—sidewalks, subways, restaurants. It’s people peopling, and your only chance of getting away from them is when you’re sitting inside your wildly overpriced apartment stressing out about how you’re going to pay the rent.

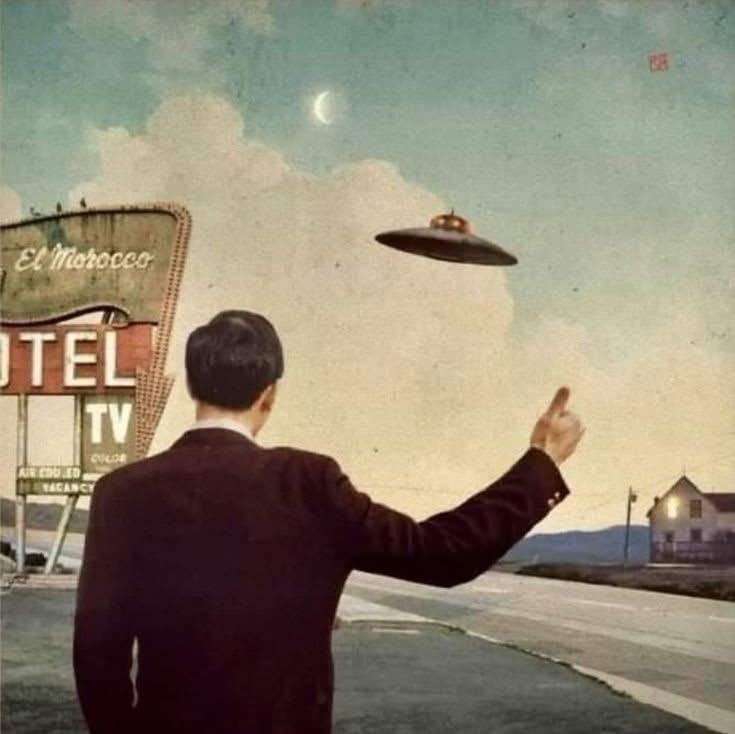

In Houston, it’s just. So. DIFFERENT. John, who lived his life in Manhattan and in Europe, had never seen a real commuter city like Houston before. Commuter cities are a Madras cloth of strip malls bleeding into freeways bleeding into suburbs. The sidewalks are a ghost town that nobody uses, and since everyone in Houston has illegally tinted windows, you rarely even glimpse a human face while hurtling along those endless loops and overpasses, flyovers and feeder roads. The human element is gone. So is the sense of shared humanity. All you behold are cars—soulless machines that they are—and pool-sized retail signs thrusting into a benzene-tainted sky, urging you to BUY BUY BUY.

There’s a Whataburger on every corner and a Jiffy Lube on every block. It’s a rinse/repeat of fast food, car lots, taquerias, pawnshops, bail bonds, pharmacies, Starbucks, and grocery stores. Based solely on landmarks, you are everywhere and nowhere at once.

Houston is what happens when you let businessmen build a city. It sacrificed beauty for convenience a long time ago. Houston is a work camp. It’s a place to live, not visit, dear to those who grew up here, and a horror to everyone else. When the Olympic Committee scouted Houston as a possible venue for future Olympic games, it bluntly rejected the city for being “too hot and ugly.”

That said, the grocery stores are palatial, prices reasonable, and parking free. I never have to skirt around some poor mental patient lolling in his own urine to enter a store. After ten years of hoofing it through Italy, which is a Stairmaster, and New York City, which is an endless slog through subway stations, I appreciate being able to park the car, walk into a store, have somebody bag my groceries, and then drive said groceries home. In the East Village, it was a mile-and-a-half roundtrip to the Trader Joe’s, and my backpack got heavier with every step. The straps are actually fraying.

Perhaps my attachment to New York City is unreasonable. It likely is. But I feel positively larval down here. After a while, the rush and confusion of Manhattan—like any other drug that’s bad for you—becomes addictive. When I was in the city, I only sporadically missed being in Italy. In Houston, I miss both—the excitement of Manhattan, and the beauty of Italy. I am a stranger in a strange land. No one speaks my language.

Churchill was right when he said, “Success is the ability to go from failure to failure without losing enthusiasm.” But the ghosts are always with me. Not for everyone the perfect Hoover lines on suburban carpets, but here we are, and it doesn’t look as though we’ll be leaving anytime soon.

If the purpose of life is to simply live it, which I believe it is, then we’re exactly where we need to be.

Here’s the kicker: You probably are, too.

I'm glad you landed safely, if not satisfyingly. It's like the old saying: "The bad news is: nothing lasts forever. The good news is: nothing lasts forever." If you have to move again, come to Las Vegas! This is a great live music town.

There she is. We’ve missed you