Given how tiresome I find the obsessive repetition of the female nude in paintings, it might come as a surprise to learn that Italian-Jewish artist Amadeo Modigliani, the undisputed heavyweight title holder for the depiction of female nudes, is one of my all-time favorite painters.

It’s a crowded field, these nudes. Even a casual trip to the museum can yield literally hundreds, from Titian’s beefy backsides to Picasso’s flat, triangular breasts, and after a while—for me, at least—I have to ask myself: was there really nothing else to paint?

Were more female artists admitted into the salons of the early 20th century, would their subjects have been any different? I like to think there would have been older women or pregnant women or naked men. All too often, these white-guy paintings seem like a long, oil-paint-scented seduction, “Nude Woman on Bed,” the model pinned there like a captive butterfly warily waiting for the artist to pounce.

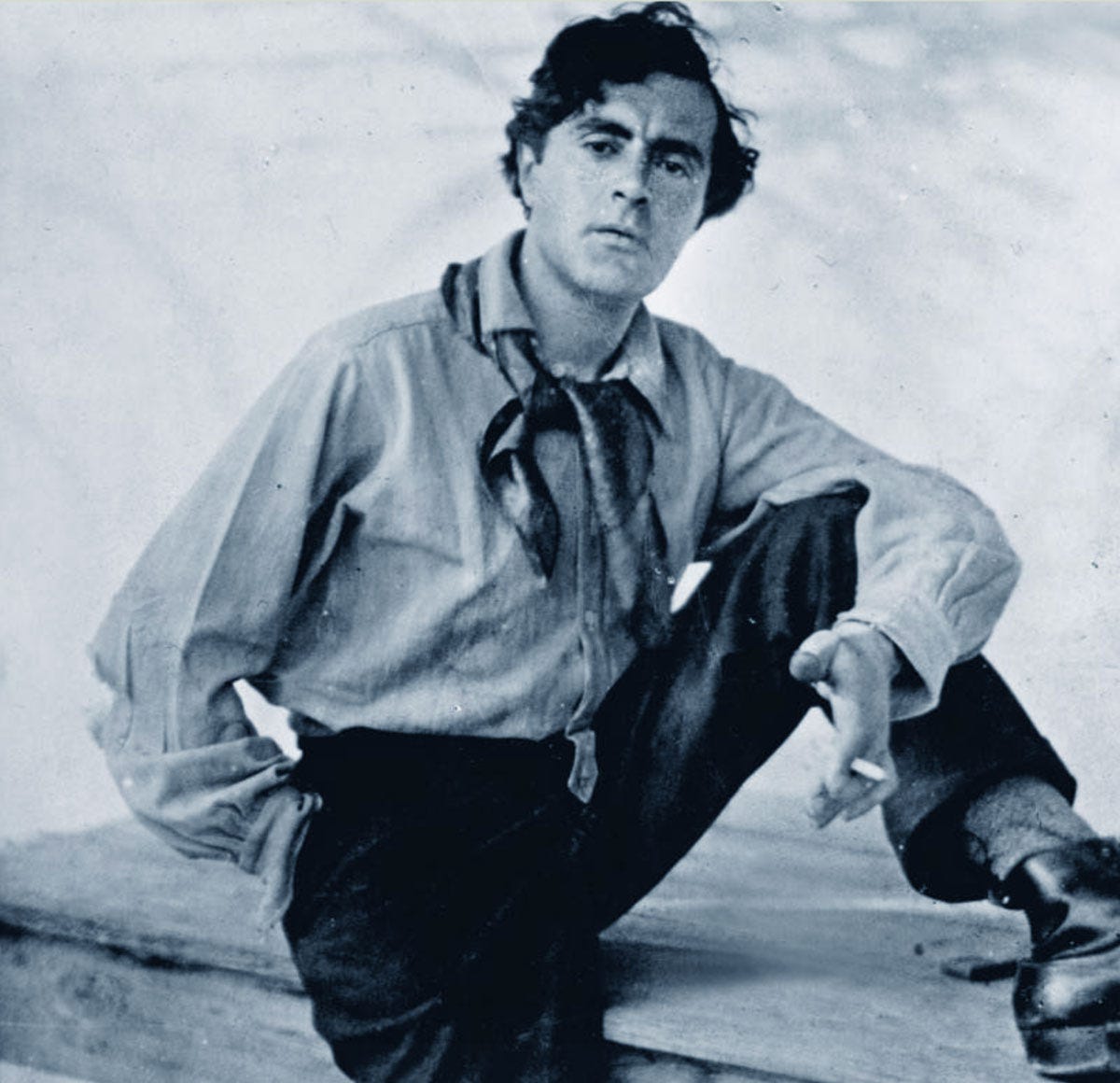

How then do I justify my adoration of Modigliani? As a man, he was indefensibly awful. In his short, tragic life, he managed to do considerable damage to the people around him. But let’s start there, and then I’ll tell you what I see in his work.

At thirty-five, Modigliani died in penury of tubercular meningitis, a disease which had plagued him since the age of sixteen. There are many scholars who believe that Modigliani’s excesses and hedonism are a direct result of his mortality salience: he knew he was going to die. Still others suspect that he exaggerated his insobriety as a way of masking the worst symptoms of the disease. Being drunk was okay; being infectious wasn’t.

People with tuberculosis were pariahs, forced to live in isolation due to its fatal transmissibility, so Modigliani certainly had reason to conceal his illness. By 1900, TB was the leading cause of death in Europe. Whether his voracious drug and alcohol use was a charade to disguise his condition or a means of denying how afraid he was to die, no one really knows, but after years of remission and reoccurrence, the disease had already reached its advanced stages by 1914.

In the period between the two World Wars, Paris was a marquee scroll of the art world’s most famous names. By the time Modigliani arrived in Paris in 1906, it was already a hot bed of avant-garde edgelords like Pablo Picasso, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and Moïse Kisling. Within a year, their influence on Modigliani was such that not only did he disdain all his previous work, he destroyed it. “Childish baubles, done when I was a dirty bourgeois."

In a haze of hashish and absinthe, Modigliani sketched and painted almost compulsively, pulling out paper and pencil at cafes and dinner parties, his mind restlessly searching for its next inspiration. At his only solo exhibition, Modigliani’s nudes, now considered to be his most famous paintings, attracted such a throng, the local constabulary insisted the paintings be taken down.

His sculptures may have been made from limestone stolen from the Montparnasse district where he lived. Stone was beyond the financial means of any poor artist. As one of the last Parisian neighborhoods to be renovated, Montparnasse had a wealth of limestone to “liberate.” Is it a coincidence that Modigliani’s series, Heads, was made of that exact substance?

During his lifetime, he created and sold a number of works, but that money soon disappeared into the vortex of his addictions.

In the spring of 1917, Modigliani met a winsome nineteen year old named Jeanne Hébuterne, who became his mistress and artistic muse. Despite her family’s hysterical objections, Jeanne moved in with Modigliani and bore him a daughter—not his first illegitimate child by any means, since there was already a son by a previous mistress, in addition to two other offspring.

But Modigliani’s health was rapidly deteriorating. By the end of 1919, he could barely get out of bed. Jeanne, who was eight months pregnant with her second child, could do nothing more than hold him in her arms as he raved deliriously. He died on 24 January, 1920. She was taken to her parents’ house where, grief-stricken and inconsolable, she threw herself out a fifth-floor window the day after his funeral, killing herself and her unborn child. Such was the animosity of Jeanne’s family, they would not allow her body to be moved to rest beside Modigliani until 1930.

For tropes about brilliant, tortured, and destitute artists, one needs look no further than Amadeo Modigliani. Now, of course, his work fetches astronomical sums. On 9 November 2015 the 1917 painting Nu couché sold at auction in New York for a record-setting $170.4 million.

I find myself wondering what he might have thought about that. If such amounts had been available to him in his lifetime, would they have assuaged his financial insecurities and made him less prone to self-destruction? Or would they have hastened his debauchery and demise? As the daughter of a mad genius who vandalized himself with drugs and alcohol, I’m inclined to believe that nothing would have mitigated Modigliani’s fury at his premature death sentence. His fear must have made him hopelessly self-absorbed—certainly his disregard for the feelings of others can attest to that—but that darkness also made him the unabashed hedonist who created works like these:

Here is what I see in him.

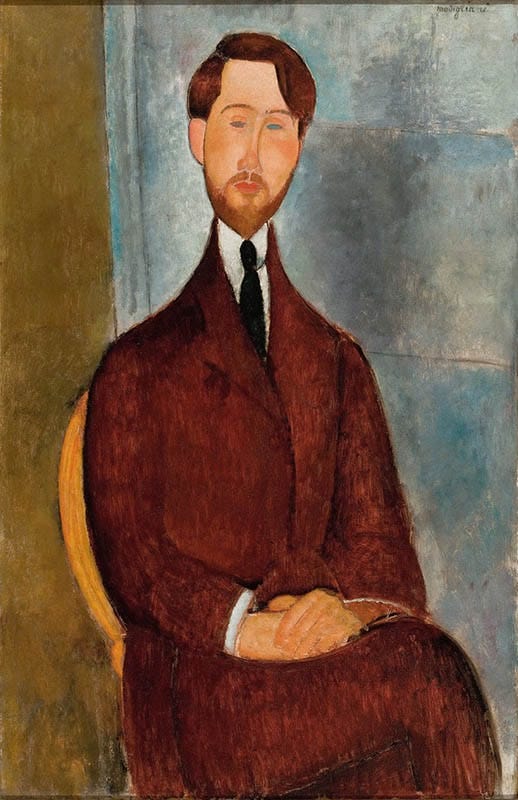

Despite wanting the approval of his peers, Modigliani refused to be categorized by any of the multiple “isms” of the period. One can detect the Cubist influences, but Modigliani is not strictly Cubist. He also became casually involved with the Fauvists (the word means “wild beasts”) where vigorous brushwork and intense colors are intended to convey the emotional state of the artist. But how to explain the distinctly African lines of his sculptures or the elongated, almond-eyed, mask-like faces in his paintings? Modigliani is all of these things and none of these things simultaneously. He is his own creation.

And this is why I can easily forgive the somewhat hackneyed “male gaze” narrative of his work. Take a close look at the women he paints. These are not passive objects, but active participants—not in their own sexual exploitation, but in their own lives of psychological awareness and complexity. By all accounts, Modigliani had a close and healthy relationship with his mother, a remarkable woman in her own right. I believe that his regard for women as intelligent and autonomous individuals is reflected in his work, especially in the bold sensuality of his models. These are women who are comfortable with your admiration. Nothing is being taken and coerced from them. They don’t exist solely for your pleasure.

Aside from being the progenitor of pubic hair, then considered to be a scandalous indecency, Modigliani left behind a stranger legacy: he is one of the most faked artists in the world. Kourtney Kardashian and her erstwhile husband, Scott Disick were fooled by a fake Modigliani painting. As the art market dries up and fewer dead male European artist’ paintings are made available, it will be interesting to see what sorts of shenanigans forgers get up to next.

Modigliani redefined the tradition of the nude. Gone is the modesty and mythological subtext. No apologies are made for the frank gaze of his subjects. Given the attractiveness of the artist himself, I suspect the sexual desire we see was strongly reciprocated, and that alone makes his work fascinating.

Do you like, dislike, or feel indifferently toward the work of Amadeo Modigliani? I’d love to get your hot take on the matter, so feel free to comment below.

I confess his work is not what I would call "arresting, but most of my artistic taste begins and ends with the late Renaissance Dutch masters. (Given the choice between a Rubens print and a genuine Modigliani in my house, I'd go with the Rubens.) I can begin to see some of the things you talk about in the pictures you shared, but I still have to work on it.

By the bye, what you said about the male gaze (I keep wanting to change that to "glaze"), much of this stuff owes its origin to Renaissance pornography. You might enjoy reading Lisa Jardine's "Worldly Goods: A New History of the Renaissance." Books like Jardine's (and, of course, Braudel's magnificent 2-volume set) are part of what got me hooked on the Ren Faire, because they focus on the physical *things* of life in the era, rather than just ideas &/or sequences of events.