When people ask me why I moved to Italy, I often give them my “overall reasons”—I fell in love with the country and fell in love with a man who lives here. Seems pretty self-explanatory, right?

But what I usually leave out is how impossible it would have been for me, had I stayed in the U.S., to transition from working seven days a week as a group fitness instructor and personal trainer, while writing part time, to becoming a full-time freelance author. Impossible not in the hyperbolic, poor-me sense, but literally impossible. And one of the biggest obstacles to me staying in my native country and fulfilling not a dream but a destiny was the lack of affordable housing.

I lived in Houston, which may not yet have achieved New York City prices, but has been climbing steadily upward. In 2008, I moved into a ratty apartment behind a shopping mall that cost me $750.00 in rent. My son and daughter had to share a bedroom. By 2014, I was paying $1600 a month. I went from having to work five days a week to busting my hump all seven (Houston’s frequent natural disasters, hurricanes, and floods, were automatic time off, but always without pay.)

In just a few short years, life had depleted me. Every time I sat down to write, I’d either fall asleep with the pen in my hand or I couldn’t hold the pen at all. I thought it was nerve damage from lifting weights. It turns out I was just exhausted.

I was hardly alone. Artists everywhere have side hustles that are anything but. The need for money overwhelms all else. Ironically, artists are major contributors to the economy, often making the difference between a city that’s vibrant and exciting and one that tumbleweeds blow through.

Case in point.

Artists create a cultural economy, one that pulled in $763.6 billion in 2015 and employed almost 5 million Americans, according to a Bureau of Economic Analysis and a National Endowment for the Arts study. But there’s a whole second-tier event-related, economic spinoff, like dining out before seeing a show, for instance, that supports 2.3 million jobs and injects another $15.7 billion into the national economy. That’s not chump change.

Every time you sit down in a restaurant patio, pop open a cold one, and listen to music, you are participating in that cultural economy. Reading this article, you are participating in that cultural economy. Those gorgeous, building-sized murals downtown? An artist or possibly a team of artists create those, and they not only need unstructured time to ply their craft, they need an affordable place to lay their heads at night.

There are more artists in the United States than coal miners. We need to pay attention to this issue.

Without help, artists can’t afford to make art. They’re hustling to pay rent every month, not to mention the thousands of dollars in other expenses (cell phone service, food, healthcare, an internet service provider, a car.) No wonder so many talented artists give up their creative work and start pulling 40+ hours a week at UPS. They back-burner their dreams because they have to.

These aren’t people looking for hand-outs while they “play artist.” These are serious professionals, ones who have the power to salvage local economies. Twelve years after being devastated by Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans took in over $9 billion the year before Covid struck, and that city’s glorious jazz offerings were the biggest draw.

My brother, acclaimed tenor saxophonist Ellery Eskelin, lives in a hi-rise called Manhattan Plaza in New York City. The building is subsidized by the city for the specific purpose of housing artists. Without it, Ellery would have never been able to afford New York City prices while working as a jazz musician. The waiting list to move into Manhattan Plaza is years long.

Every major U.S. city needs a Manhattan Plaza—more than a few. If you think the affordable housing crisis just affects poor people, imagine what a soul-crushing reality it is for artists; poor but driven to create, yet without the means to do so.

A thriving arts community doesn’t just pull in tourists and spur economic growth, it entices well-educated, affluent millennial tech workers to gentrify shabby neighborhoods—neighborhoods that artists make appealing but price themselves out of.

This is why affordable housing for artists is a must. Commercial property developers must be incentivized to create low-income artist housing by having their federal tax burden reduced. In cities like New Orleans, subsidizing its artist and musician community is taken seriously. After Hurricane Katrina, three abandoned buildings that became the Bell Artspace campus were transformed into 79 affordable units for low-to-moderate-income artists. Even its common spaces were repurposed for creative use.

We need more of this. A lot more of this.

Would I live in the United States again if I could afford it on my freelance wages? Yes. So would my boyfriend, a native New Yorker, who has worked as a jazz drummer his entire life. We miss our families. We miss our language. We miss our culture. But until a place is made for us and others like us who have fled to Europe in order to survive, that dream is a rainbow that vanishes the moment you think you’ve found it.

We are exiles, even on native soil. And entire communities, townships, and states suffer because of the marginalization of artists.

Make room for us, and we will create things of beauty that everyone can enjoy. We can raise cities from the ashes of Covid and decay. We have the ability to transform lives and inspire future generations. We translate our moment in time into words, music, dance, images. We reflect back what you see every day, only in technicolor.

This world needs artists.

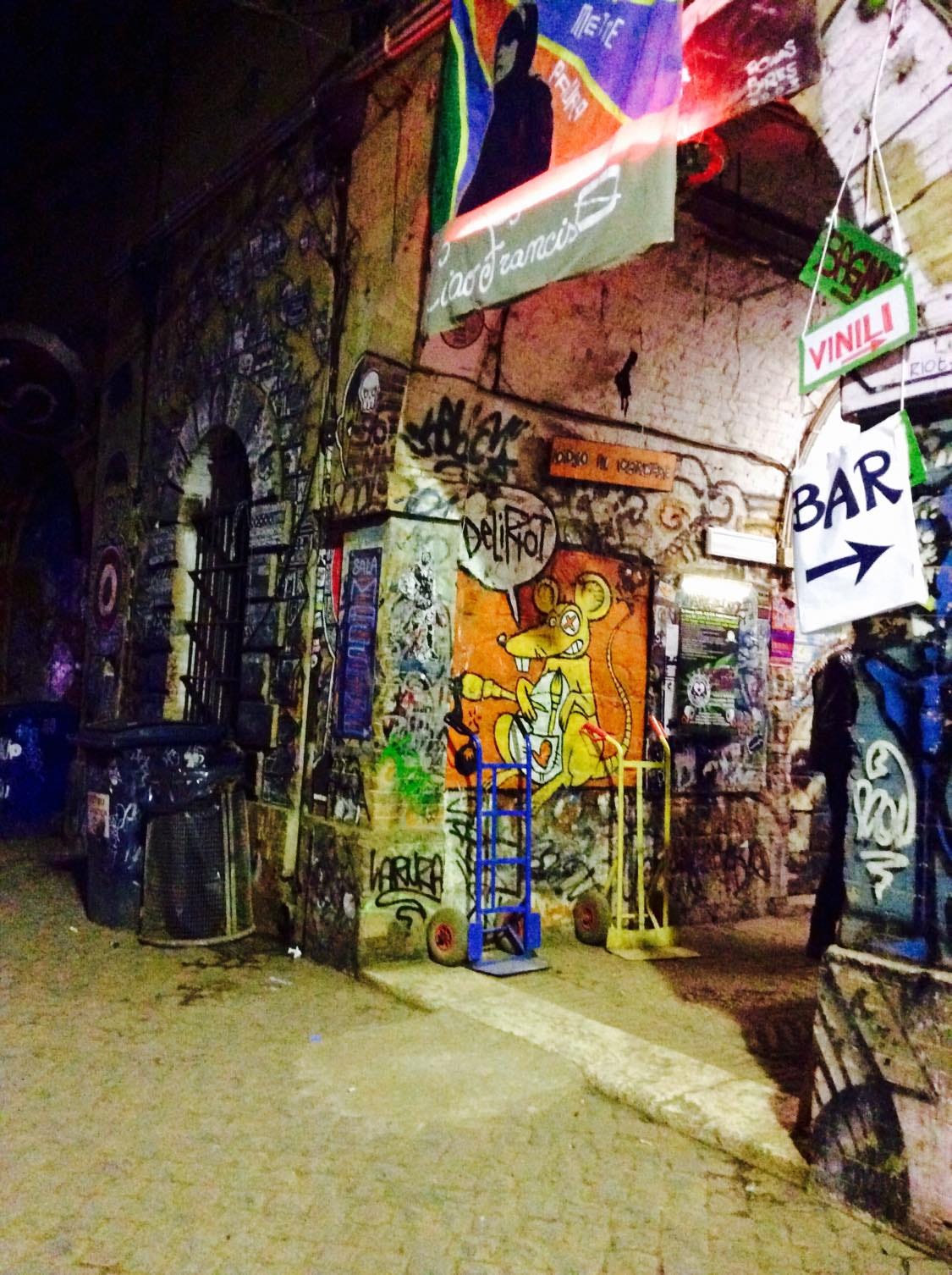

Thank you for this article. I also wanted to fill you in on the background of the second photo. The mural in Łódź, Poland is of my dad, Janusz Głowacki, who was a Polish-American writer. The mural was painted by a Polish artist, Andrzej Pągowski, after my dad passed away suddenly in 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/22/theater/janusz-glowacki-dead-polish-playwright.html. "Głowa" was his nickname, a shorted version of his last name and it also means "head" in Polish. So the closest translation I can come up with is "And how can we keep living without our heads?/without Głowacki?'

Portland is experiencing much of the same problem, with artists/writers/musicians being priced out of the market and being forced to flee to more affordable markets. Political cartoonist Matt Bors comes to mind. He ended up having to move to a small town in Ontario...and he's a fairly well-known name in his field.

I'm fortunate in that I don't have the financial pressures most creative types do, but if I was living by myself, there's no way I'd be able to do anything but work to support myself...and my writing would suffer for it. I'm no Tom Friedman or Eugene Robinson, but I think I have something to add to the public discussion.

The problem is that America is a country that loves and enjoys consuming the work of artists, musicians, and writers...it just doesn't want to pay for it. What if we all decided we want to drive cars but didn't want to pay for them? It's the same thing, yet few see anything wrong with it.