Italy's Bloody "Years of Lead"

Part 1 of a 2-part series recounting one of the most terrible periods in Italian history.

Like most Americans, especially those suffering the misfortune of having been educated in Texas by teachers with no more true understanding of history than an ape with syphilis, I had no idea that from the late 1960s to the early 1980s, Italy experienced one of the bloodiest outbreaks of political terrorism among all western democracies.

In fact, I was so astonished to hear of it, I remember exactly where I was when John first introduced the subject (in the car on our way to Rome, John wearing his signature black T-shirt and jeans; me in a dress I wouldn’t dream of wearing these days on account of chafing and possible tackiness). I couldn’t believe what he was telling me about Italy’s Anni di Piombo, Years of Lead, a fifteen-year long period characterized by terrorist attacks from the radical fringes of both liberal and conservative movements, resulting in over twelve hundred casualties and the murder of a greatly beloved prime minister, Aldo Moro, whose body was eventually discovered in the trunk of a red Renault 4 parked on a side street in Rome.

That’s a lot to take in. A lot.

I remember gazing out of the car window at the serene beauty of the Italian countryside, the graceful pini romani, or “umbrella pines,” her undulating hills and ample valleys, the plodding Flaminia, a two-lane road that, like all roads, leads to Rome, and I just couldn’t get it to jake up in my head.

In the U.S., the political left is largely pacifist. We’re the ones staring down stormtroopers in riot gear by sliding daisies into their gun muzzles. Yet here in Italy, the left was anything but pacifist, murdering their enemies in cold blood.

I was immediately reminded of the true heroes of World War II, at least in Italy, which were the partigiani italiani, partisans who were brave enough to conduct guerilla warfare against their German occupiers. Were the Years of Lead merely an extension of that struggle, or were they the result of something deeper?

Terrorist organizations proliferated in Italy during this period. Communist and leftist groups such as the Red Brigade had the greatest number of members and did the greatest amount of damage, but neofascist militant groups like the Nuclei Armati Rivoluzionari (NAR), “Armed Revolutionary Nuclei,” did terrible things, such as bombing a train station in Bologna and killing 85 people—a horrific act I will talk about in greater detail in tomorrow’s Cappuccino.

Unlike the Red Brigade, who targeted specific enemies, the NAR committed acts of terror with indiscriminate glee. Their leader, a former child actor, once said, “About defeat we never cared, we are a generation of losers, always on the side of the defeated,” which sounds remarkably like the disaffected youth dynamic that often springs up in countries that have been on the losing side of a war.

The trouble began in earnest on 19 November 1969 when a twenty-two-year-old Milanese policeman named Antonio Annarumma was beaten to death with a lead pipe by far-left demonstrators. It had already been a year of student unrest and building occupation, so by the time the union rally that led to Annarumma’s death was underway, tempers were at a boiling point. After Annarumma was struck, he lost control of his vehicle and hit another police officer, which further inflamed neofascist sentiment against the left.

Shortly thereafter, on 12 December 1969, a bomb exploded at the corporate offices of Banca Nazionale dell’Agricoltura in Milan’s Piazza Fontana near the Duomo. Seventeen people were instantly killed and eighty-eight wounded. Later that same day, three more bombs went off in Rome and Milan, an attack that had been organized by the neofascist paramilitary group, Ordine Nuovo, or “New Order,” in clear retaliation to leftwing terrorism.

Initially, anarchists were blamed, specifically a railway worker named Giuseppe Pinelli who, much like Putin adversaries of today, “fell” from a fourth-floor window of the police station where he was being detained. Later inquiries absolved the police of any wrongdoing, but … who knows? Leftwing faction Lotta Continua (The Struggle Continues) blamed police commissioner Luigi Calabresi for Pinelli’s death, meting out their own form of street justice a year later when they killed him.

Then on 31 May 1972 came the Peteano bombing, which killed three carabinieri. At first, the Lotta Continua was blamed, but it was later discovered that a neofascist Ordine Nuovo member named Vincenzo Vinciguerra planted the bomb. In a tale as unlikely and convoluted as anything coming out of American rightwing conspiracist Alex Jones’ studio—and yet true—Vinciguerra stated that the bombing had been a false flag operation intended to force the Italian government to become more anti-communist. He claimed that he’d been aided by Italian Military Secret Service, who orchestrated the attack and then tried to pin it on the Red Brigade.

In 1973, after the Peteano bombing, there came the 16 April arson attack carried out by leftwing terrorist organization Potere Operaio (Workers’ Power) on the house of a neofascist militant in Rome, resulting in the deaths of his two sons, one aged 22, the other 8.

They were burned alive.

In May of that year, during a ceremony honoring police commissioner Luigi Calabresi (before his assassination), an anarchist with rightwing affiliations named Gianfranco Bertoli threw a bomb that killed four people and injured forty-five more. Interesting side note: the American CIA is a stench that permeates much of the activities of this period, always difficult to prove, but unmistakable nonetheless. It was a time of outsized paranoia regarding the encroachment of communism, so their involvement is likely.

Consistent with their thirst for mass destruction, the Ordine Nuovo detonated a bomb during an anti-fascist rally in Brescia, murdering eight people and wounding 102 others. In August, 12 more were killed and 48 injured when a neo-Nazi organization called Ordine Nero (Black Order) bombed an express train.

This went on for years—leftwing terrorists assassinating specific targets, and rightwing terrorists killing randomly and in large numbers as a bloody form of rebuttal. The NAR and their other fascist paramilitary brethren were not only revolting against the state’s centrism, but also watered-down versions of their own warped philosophy, in particular those who, as the NAR put it, “go on polluting our youth, preaching wait-and-see and the like.” But at its most basic, the movement gave vent to Italian youth’s counterculture rage and feeling of betrayal by the fatherland—and on a more intimate psychological level, possibly their own fathers.

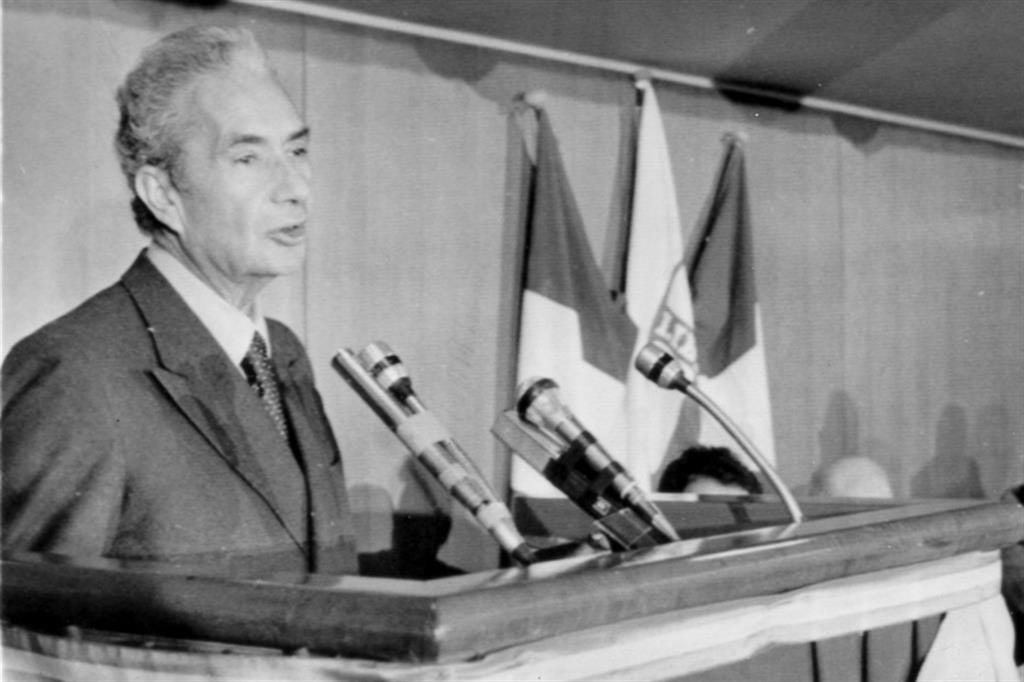

Then on 16 March 1978 came the kidnapping and murder of former prime minister (and John F. Kennedy equivalent) Aldo Moro. A unit of the Red Brigade blocked a convoy ushering Moro through the streets of Rome. Red Brigade members murdered all five of his bodyguards and shoved him into a waiting car. In one of life’s greatest ironies, Moro had been on his way to Italian Parliament to lend his support for a new government that would have, for the first time, espoused the aims of the Italian Communist Party. In other words, the Red Brigade.

So why did the Red Brigade kidnap Moro? Their motivations are vague, even now. Ostensibly, they wanted to do a prisoner swap, but it is this writer’s considered opinion that they also wanted to flex their political muscle, instill fear, and show the world what they were capable of.

Within hours, a manhunt was underway to find Aldo Moro. Pope Paul VI, a personal friend of Moro’s, offered himself in exchange. Three Bolognese professors claimed to have a tip, which was later discovered to have been given to them during a séance using a Ouija board.

Despite pleas from the president and prime minister, the government took a hard line on negotiating with terrorists, so the Red Brigade had a “people’s trial” for Moro, in which he was found guilty and sentenced to death. They made one last attempt to persuade the Italian authorities that they were prepared to kill him, but to no avail. On 9 May 1978, Moro’s kidnappers put him in a car, shot him ten times, stuffed his body into the trunk, and then left the car on Via Michelangelo Caetani.

The discovery of his body plunged Italy into national mourning.

Tomorrow, I will detail the 1980 Bologna massacre, the controversy over who was ultimately responsible (hint: it might have involved the Italian Secret Service), leftwing terrorist Cesare Battisti who was arrested in 2019 for crimes he committed during Italy’s Years of Lead, and then (***rubs hands together in anticipation***), one of the most fascinating and depraved organizations in Italy: P2, Propaganda Due, an honest-to-God Masonic Lodge founded in 1877 which later became a clandestine, rightwing criminal syndicate that ordered the assassinations of journalists, bankers, and others before masterminding the collapse of the bank of the Holy See.

So, be sure to stay tuned. There is no country more complex, more bewildering, more infuriating, or more inspiring than Italy.

And hey, we’re just getting started.

Copyright © 2022 Stacey Eskelin

What are your thoughts? I want to hear them! Leave your comments in the comments section below.

I remember the Aldo Moro incident, and some of the rest. Italy, as they say, was a f*****g mess, but it was only the worst example. In 1985, I was shepherding a group of high school students through Syntagma Square in Athens. Five hours later, someone set off a bomb- ineptly, and in typically Greek fashion as it turned out. Only a few shops were damaged, but the intent was to kill many American tourists.

Europe was fun then, wasn't it??

June of 1975 is when I enlisted in the army. I shipped out to Germany in ... derp, w/o looking at my DD214, I'd say a year later. In those days, the Baader-Meinhof (Germany's version of the Red Army Faction) were busy partying it up. I didn't know names or dates, but I knew that the shit was going down in Italy as well.

People forget that, back in those days, there was still an East Germany (I was stationed 12 kliks from the border. On the *west* side, I mean.) Active communist insurgent groups were a very real thing in those days, and even I sometime forget how tense things could get. (There was a day on the tac site when our good friends on the other side of the wire flew an unmarked DC-3 over the border trailing a banner that said "Yankee Your Day Is Coming." Well, the thing was loaded to the gills with ECM (Electronic Counter Measures) equipment, so we just put our radars into standby and let them have their little joke. No point in feeding them valuable intel about our equipment.

Part of me is hesitant to call a militant organization that exclusively targets relevant individuals "terrorist" in the strictest sense of the word. Terrorism (in my very "Professor Twist" sense of the word) is about *terror* in the general population. So, while Italy's RAF would have given me no notice, their neo-fascists would have been just as happy to blow me to Jesus as the next random bystander. I'm not aware of a good term to distinguish between the target versus arbitrary violence, but it seems to me like there ought to be such a term, because there is something important happening in the difference.

I wonder of the reason Italy took a hard line re: Moro's abduction precisely because of what he was about to do?