Italy's Bloody "Years of Lead": A Train Station Bombing, a Poet-Assassin, and a Masonic Lodge

Only in Italy are such things possible. Part 2 of 2.

In yesterday’s Cappuccino, I detailed some of the more appalling (and poignant) moments from the Anni di Piombo, “Years of Lead,” a period in Italy’s history spanning the late sixties to the early eighties. They were called the Anni di Piombo because of the hail of gunfire that rained down on a country already struggling to come to terms with its role in World War II. Extreme fringes of the political left and right engaged in acts of terrorism, ridding themselves of perceived enemies, including former Italian prime minister, Aldo Moro, who was kidnapped, shot at point-blank range, stuffed into the trunk of a red Renault 4, and parked on a side street in Rome as a grisly memento for the country that loved him.

In the United States, we tend to relegate such horrors to “Things That Happen to Other People in Other Countries.” This is a mistake. What happens in other countries can and will likely happen in the U.S. In fact, it already is happening.

That is why I’m taking time to write this two-part series on Italy’s Anni di Piombo.

The particulars of this period in history are three: the Bologna Massacre, which killed 85 people and wounded 200 more, the years-long manhunt for leftwing terrorist Cesare Battisti, and the involvement of the P2, Propaganda Due (Propaganda Two), an actual, non-apocryphal 19th century Masonic Lodge-cum-criminal syndicate that was likely complicit in the Bologna Massacre.

One of the things I find most fascinating about Italy is she’s always got both feet in the boat. No half-measures here. She’s all in or all out, but never in-between, whether for good or ill, and there’s just something operatic about that.

So. Here we go.

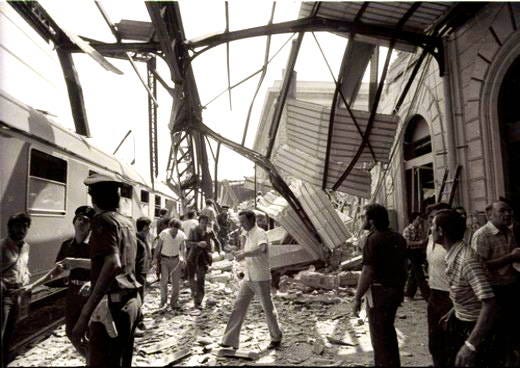

The Bologna Massacre

The morning of August 2, 1980, was hot and dry like most August mornings in Italy, with the promise of an afternoon heat index rivaling Dante’s Inferno. Flies buzzed listlessly around the train station in Bologna, a multi-use building also housing the offices of catering company Cigar. But the waiting room was packed with Italians eager to get started on their month-long holiday, and foreign tourists burdened by heavy backpacks, crinkled maps, and a grim determination to not let the debilitating Italian heat derail their vacation fun.

This was, of course, why so many people had crowded into the air-conditioned sala d’attesa—to escape the heat. Among them was a twenty-year-old Japanese student named Iwao, from Tokyo, whose greatest desire was to study Italian art, language, and culture. In fact, he’d won a scholarship from the Italian Cultural Center in Tokyo, which was how he came to be at the train station on that fateful day. In his diary, he wrote: “August 2: I'm at Bologna Station. Called Teresa but no show. So I decided to go to Venice. I take the train at 11:11. I bought a travel basket that I paid five thousand lire for. Inside there is: meat, eggs, potatoes, bread and wine. As I write, I'm eating.”

It was his final entry.

Forty-year-old Natalia Agostini, mother of two, was at the station with her husband and eleven-year-old daughter, Manuela. They were waiting for the train that would have taken Manuela to summer camp in Dobbiaco, a lovely lake region in the province of Bolzano. Natalia’s husband left the waiting room to buy a pack of cigarettes just as the bomb exploded. He sustained mild injuries, but Natalia and Manuela were crushed beneath the rubble. Mother and daughter were transported to the hospital, but died a few days later without regaining consciousness.

In the offices of Cigar right above the waiting room of the train station, twenty-five-year-old Nilla, an only child, the apple of her parents’ eyes, was about to get married. She’d already chosen furniture for her new house. The explosion instantly killed her. She died alongside her colleagues Euridia, Franca, Mirella, Katia, and Rita.

Rita was twenty-three and also about to get married.

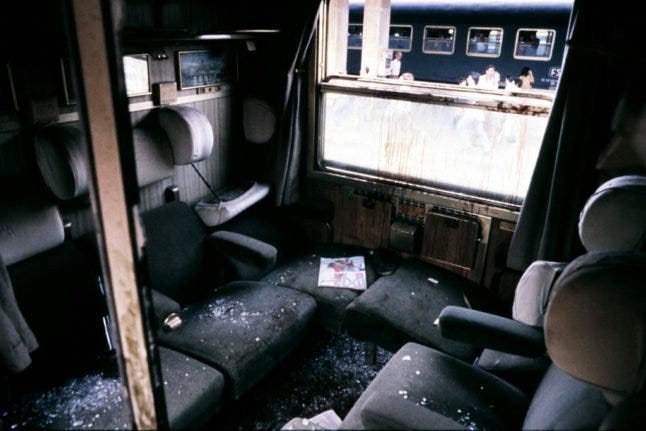

At 10:25AM, a time-bomb hidden in an abandoned suitcase detonated in the waiting room, causing most of the building to collapse. Due to the holiday period and the sheer number of dead and wounded, there weren’t enough emergency vehicles to transport victims to the hospital. Some died in agony beneath the rubble. Others were taken on buses, private cars, and taxis. The blast was first attributed to a faulty boiler, but fragments of an incendiary device were quickly discovered. The bomb itself contained 51 pounds of explosives, including 11 pounds of TNT and 40 pounds of T4.

In August of this year, 2022, President Mattarella called for “full truth” to be revealed during a speech marking the anniversary of the bombing. “It was the act of cowardly men of unequalled inhumanity, one of the most terrible of the history of the Italian Republic. The bomb that killed people who happened to be at the station on that morning 42 years ago still reverberates with violence in the depths of the country’s conscience.”

Within months of the massacre, two members of the neofascist paramilitary group Nuclei Armati Rivoluzionari, “Armed Revolutionary Nuclei,” were convicted of the crime. To be fair, most acts of indiscriminate, large-scale terrorism during Italy’s Anni di Piombo were spearheaded by fascists. Leftwing terrorist organizations, such as the Red Brigade, tended to target specific individuals.

But the NAR, never shy about taking credit for their destruction, denied any involvement. Furthermore, skeevy characters like Pietro Musumeci (pronounced MOO-soo-MAY-chee), a general and deputy director of Italy’s military intelligence agency SISMI as well as being a member of Propaganda Due (which I will discuss later in this article) conspired with Licio Gelli, financier, freemason and possible CIA operative, to sidetrack the investigation. Both men issued an order to simulate a bombing onboard a Taranto-Milan train (the order was revoked by Musumeci) in an effort to throw investigators off the scent.

Why?

Additionally, a neofascist psychiatrist named Aldo Semerari was arrested on suspicion of involvement in the attack and taken to a top-security facility for interrogation. During captivity, he suffered a psychological breakdown (Semerari had a known history of staging “psychological breakdowns” for members of the Camorra crime family as a means of enabling them to dodge harsher punishments). He was released for lack of evidence, but lived in fear that his comrades-in-arms would think he’d turned state’s evidence against them.

On April 1 1982, Semerari's decapitated body was discovered in the trunk of a stolen Fiat parked near the town hall in Campania.

The Manhunt for Leftwing Terrorist Cesare Battisti

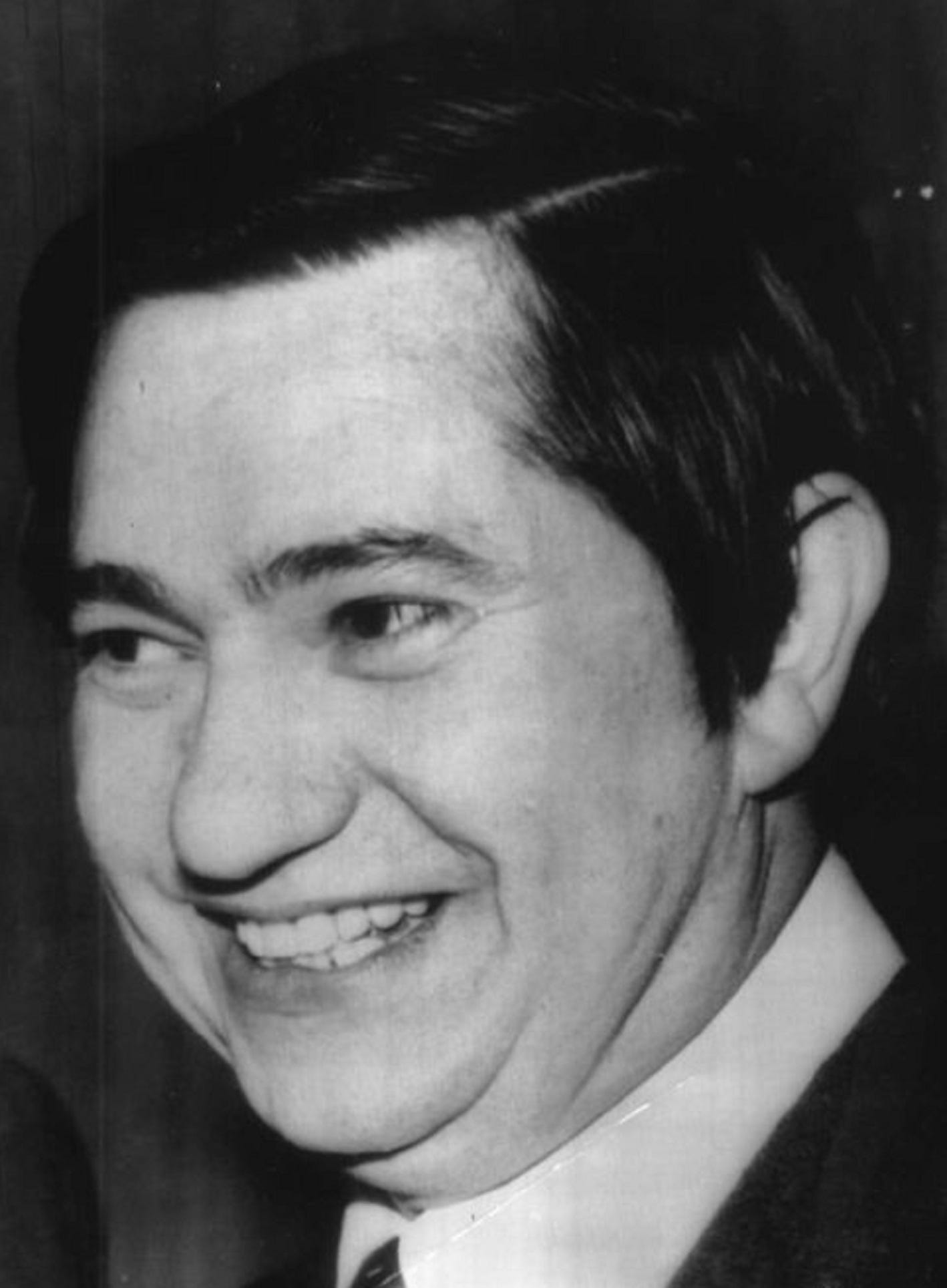

He’s almost seventy years old now, but during the Anni di Piombo, Cesare Battisti was responsible for or an accomplice to a string of tragic murders. Battisti belonged to the Armed Proletarians for Communism (PAC), a leftwing organization that masterminded hits, robberies, and terrorist activities.

The rightwing target of their wrath on 16 January 1979 was a jeweler named Pierluigi Torregiani, whom PAC wanted to kill in retribution for the death of one of their own men during a botched restaurant robbery.

Their target, Torregiani, suffered from lung cancer. During his treatment at a hospital in Milan, he befriended a widow, also ill, with three underage children. When the widow died, Torregiani and his wife adopted all three of their children: Anna, Marisa, and Alberto.

On the night in question, Torregiani was attacked by three members of PAC, pulled out his gun to defend himself, and accidentally shot his own teenaged adopted son, Alberto, who was paralyzed and even now remains confined to a wheelchair.

That same day, Battisti murdered a butcher, far-right militant Lino Sabbadin, who lived near Venice. Sabbadin had killed a PAC member during an attempted robbery the previous year; now, he was dead.

In 1978, there was a prison guard named Antonio Santoro, aged fifty-one, who lived and worked in northeastern Italy. Battisti shot and killed him for allegedly mistreating prisoners.

Andrea Campagna was a driver for the Digos anti-terrorist law enforcement agency. He was twenty-four. Battisti shot him in the back of the head.

Battisti was arrested, convicted, and imprisoned for these murders in 1979. Then, on 4 October 1981, PAC members organized his escape. He first fled to Paris and then to Mexico, returning to Paris in 1985 after French president Francois Mitterrand, a committed socialist, proclaimed that “leftist Italian activists who were not indicted for violent crimes and had given up terrorist activity would not be extradited to Italy.”

Having now written fifteen admittedly poetic thrillers focusing on exile, redemption, and the changes of heart even a hardline activist can undergo, Battisti must have felt as though his sins had been expatiated. But in 2004, the admittedly not socialist government of Jacques Chirac decided to extradite Battisti back to Italy, causing him to flee to Brazil by using a fake passport.

For three years, he managed to stay under the radar. Then in 2007, Battisti was discovered and arrested in Rio de Janeiro where he spent four more years in custody until Brazil’s leftwing president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, who rejected Italy’s request for extradition.

Battisti was a free man.

But Brazil has a mercurial judiciary. After the election of ultranationalist Jair Bolsonaro, Battisti made it across the border to Bolivia, where he was promptly extradited back to Italy to face charges.

Now, it’s 2022, more than forty years after Battisti’s reign of terror, and there is a movement afoot to exonerate Battisti in the court of public opinion. I’m pretty lefty, but even I don’t believe his innocence. Battisti murdered people. He may have later regretted it, but does that make him any less a threat to society?

Sinister Mastermind Licio Gelli and an Honest-to-Goodness Masonic Temple That Doesn’t Fall Under the Rubric of Illuminati Nonsense

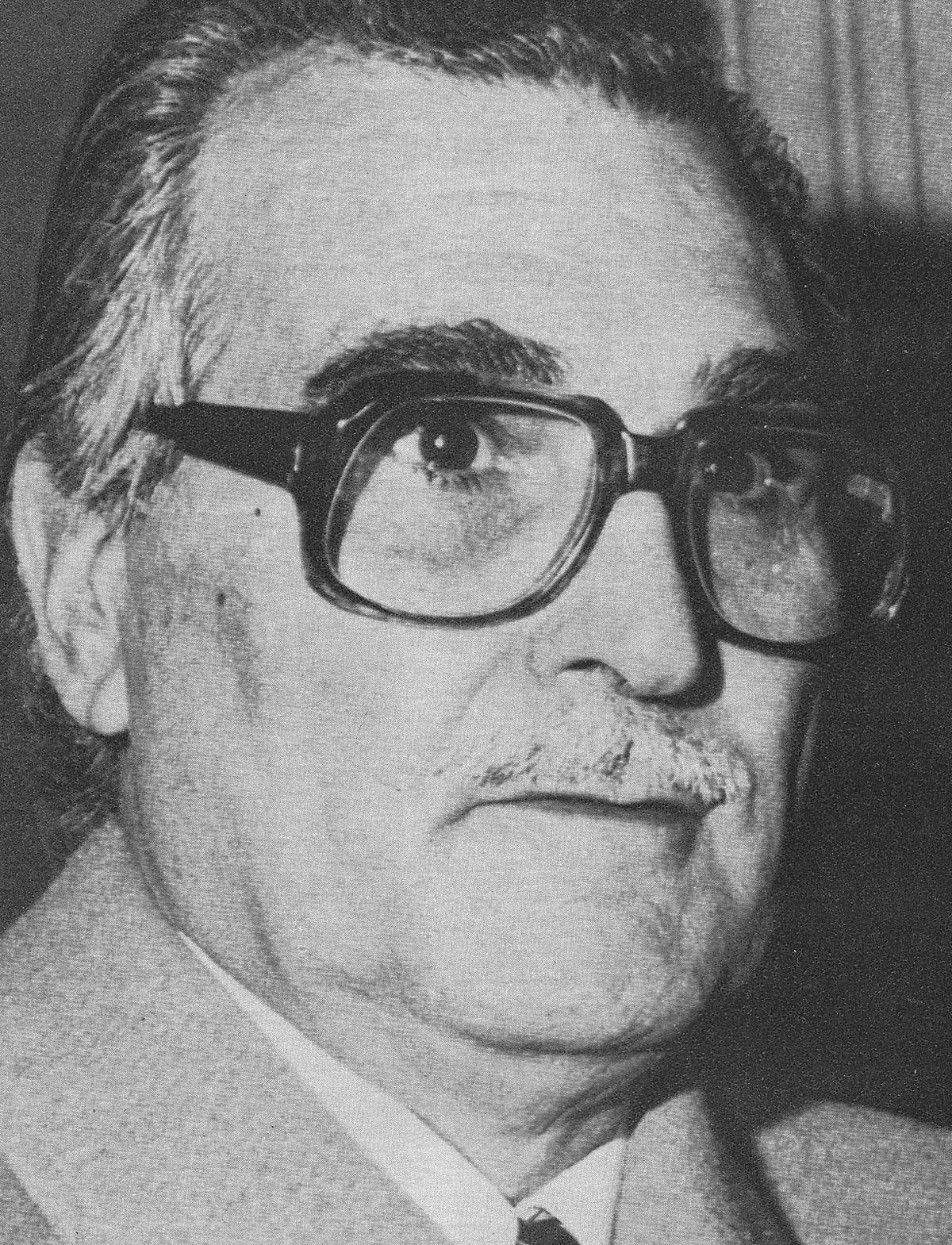

It’s impossible to talk about P2, or Propaganda Due, without referencing fascist financier and “Worshipful Master” of P2, Licio Gelli, one of the shadowy figures implicated in the coverup of the Bologna Massacre.

As a young man, Gelli had volunteered to serve as one of Mussolini’s notorious Blackshirts, a paramilitary wing of the National Fascist Party who were the scourge of Italian partigiani—heroes who resisted German occupation.

P2 was (is?) a secret society founded in 1877 and largely referred to as a “state within a state” or a “shadow government,” likely due to their outsized influence on Italian politics. Members were pretty much who you’d expect them to be: prominent journalists, members of Italian government, various fat-cat industrialists, and disjecta membra from the fascist parties. Former prime minister and bunga bunga party enthusiast Silvio Berlusconi belonged. So did Victor Emmanuel, the only son of Italy’s former king and all three heads of Italian Secret Service agencies.

What an obscene concentration of power.

Even for a Masonic lodge, they had lofty ambitions. When the police searched Gelli’s villa in 1982, they found documentary evidence of what can only be described as a soft coup. A “Plan for Democratic Rebirth” one paper read, calling for the consolidation and control of the media (something which Berlusconi effectively did for a number of years), rewriting of the Italian constitution, and the suppression of trade unions.

In other words, a gutting of the heart and soul of Italy.

Because P2 was a secret society, not all of their activities are known to us, but the beginning of the end came in 1982 with the collapse of Banco Ambrosiano aka Vatican Bank. Its chairman, Roberto Calvi (he was commonly referred to as “God’s banker”) a high-ranking P2 member, was accused of funneling United States dollars to the Nicaraguan Contras using the bank as a cover.

When police apprehended fellow P2er, Worshipful Master Licio Gelli, they found yet more incriminating evidence against Roberto Calvi, who was arrested, tried, and sentenced to four years in prison. Incredibly, Calvi was released while appealing the verdict and allowed to retain his position at the bank.

Why? #BecauseItaly.

But in 1982, Calvi fled the country using a fake passport. $1.3 billion was missing from Vatican Bank, but he left his associates to clean up the mess. Calvi’s personal secretary, Graziella Corrocher, “leapt to her death” from her office window. Not long after, Calvi’s body was found hanging from the scaffolding beneath Blackfriar’s Bridge in London. In his pocket were five bricks and $14,000 in three different currencies.

In addition to killing Calvi, his secretary, and many others, P2 is widely believed to have thwarted the rescue of former prime minister Aldo Moro, whose assassination I detailed in yesterday’s Cappuccino.

P2 was officially dissolved in 1982. A law banning similarly secretive societies was passed around that same time.

So, do I personally believe that the P2 no longer exists?

Of course not. This is Italy. There will always be a criminal network of old Italian men whose waning sexual potency compel them to flex their power in other ways.

Copyright © 2022 Stacey Eskelin

What are your thoughts? I want to hear them! Leave your comments in the comments section below.

You’d think most societies would want a civil one, but history seems to keep repeating itself with power hungry authoritarianism. Which only seems to survive with a disaffected youth nourished on fear, which in turn becomes violent and militant minded for their survival, not as a human, but as a rabid animal at this point. So when fellow citizens are hunting their own, I’ll call it fucked up (lead)ership. Fascinating, yet ugly eras of Italy’s struggle for an identity.

If you really want to drop down a rabbit hole, look into the twisted trail of Calvi's associates, Michele Sindona and Cardinal Marcinkus; the so-called holy machinations of Opus Dei and its rumored affiliations with P2; and the tenuous dotted lines that connect to the Watergate conspirators and Nixon's CREEP, the FBI and the CIA.