Italy is Noisy

For them, noise is a joyful celebration of life. For others, it's a dentist's drill.

There are two resources in alarmingly short supply these days. In countries like the United States, only the very rich can afford them. I’m not talking about gas, food, or luxury items.

I’m talking about silence and beauty.

As Americans, when we see anything of beauty—a house, a view, a handbag, a pair of shoes—we automatically assume it costs more than we could possibly afford. When I first came to Italy and met John in the spectacular village of Calcata, I asked him (in my typically brash, forthright, American way) how he could afford to live in place so beautiful.

In America, if you want beauty, it’ll cost you. Even the cookie-cutter, the uninspiring, the banal, and the humdrum are going to cost you.

But Italy is lousy with beauty. It’s so plentiful, beauty is free. John and I live in one of the most breathtaking places on earth, and it doesn’t cost us extra—a fact which to this day, continues to astonish me. In America, it’s four walls of sheetrock, wall-to-wall carpeting, fixed windows that don’t open, and a view of the dumpsters, a parking lot, and the Taco Bell. If you want what passes for “beauty,” expect to turn over your paycheck.

That, my friends, is about as American as it gets.

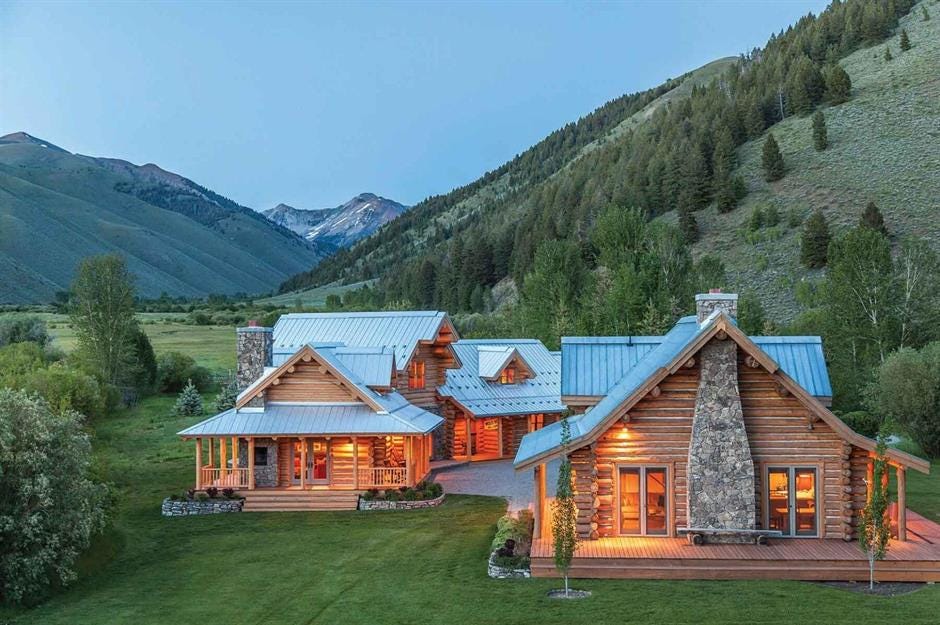

Consequently, wealthy Americans tend to live in beautiful, quiet places, houses tucked behind wrought iron gates and accessed by long driveways affording additional protection from the noise. Hilltop houses with sun-splashed terraces and panoramic views that don’t even show up on Google Maps.

Meanwhile, the rest of us exist at “street level.” It’s all car horns, pneumatic drills, blaring ads, fighting neighbors, unbaffled motorcycles, screaming children, and helicopter rotor wash—24/7.

Is creating things of beauty really that difficult or expensive? Is the deafening noise pollution most of us suffer from “the cost of doing business?” I don’t believe so. Beauty and quiet aren’t a scarce natural resource. They’re simply not a priority for most Calvinist-at-heart, no-thrills, no-frills, work-till-you-die Americans. We’re all too busy making money.

American life is noisy, but it’s not as noisy as Italian life. Most people are surprised when I tell them that. To be fair, it depends on where you live in Italy, but most of Italy is loud. Really loud.

First, it’s a country that’s half the size of Texas, but with twice the population. Housing is communal. 80% of Italians live in apartments or multi-use buildings. Second, the very building materials (stone) that have enabled this architecture to survive fires, earthquakes, and invasions for so many centuries tend to bounce sound like a hornet in a jar.

The narrow medieval street in front of our house, for instance. It’s hard surfaces on all sides—macadam, stone edifices, glass windows, oak doors. These conditions throttle sound. It has only one place to go, which is everywhere, explosively.

Living in such close quarters all their lives has, perhaps, inured Italians to the cacophony. After eight years in this country, I strongly suspect they actually thrive on it.

Your average Italian (I’m generalizing here, which is always dangerous and inherently unfair, but I still stand by my observations) has an uneasy relationship with silence. He doesn’t like it in conversation (all gaps are filled with the mellifluous sound of his mother tongue). He doesn’t like it, period. Perhaps the absence of sound reminds him too uncomfortably of the silence of the grave.

Italians are notorious for not having an indoor voice. They talk loudly, gesture dramatically, and are full of brio. It’s all part of the opera.

I find this lovely and endearing. In comparison, I am drab.

But that love of noise and frenetic activity has a less appealing aspect. During certain hours, although not continuously, the street we live on is full of noisy vehicular traffic. Unbaffled dirt bikes go roaring up the street, often at three or four in the morning. Every time we hear one coming, John and I tense up. The acoustics being what they are, those bikes sound as though they’re tearing around inside our own living room.

You might think such a source of noise pollution, generally hated by the inhabitants of Amelia, most of whom are trying to sleep at that hour, would be an easy problem to fix, one involving a quick confab with the mayor, a high-ranking member of the comune, or a member of our local constabulary.

But this is Italy. Nothing is ever that straightforward.

In Italy, the obstacles are the path.

First of all, most of those obnoxious dirt bikes belong to the sons of the high-ranking officials who make our laws. Second, the municipal traffic police, who already know that indifference is the better part of keeping a job, say things like, “We’d need an expert to come out and measure the decibel level of the dirt bikes,” which is just fancy-talk for “I ain’t doin’ sh*t.”

As though the blood dribbling out of your ears isn’t proof enough.

But it’s not just the dirt bikes. When you have multi-use buildings, there is constant warfare between commercianti and residenti, between young people who love noise and older people who just want to get some sleep.

Every year on the 14th and 15th of August is a nationwide holiday called ferragosto. The bar owners obtain noise permits to blast music until 3AM. But it’s not as though warning is given. Like all things Italian, you’re just supposed to know—through osmosis, perhaps—that ferragosto will be a loud, obnoxious Bacchanalia and you’d be wise to head for the hills. For those of us caught flat-footed, it’s an auditory assault that jangles nerves, induces migraines, and makes the windows rattle.

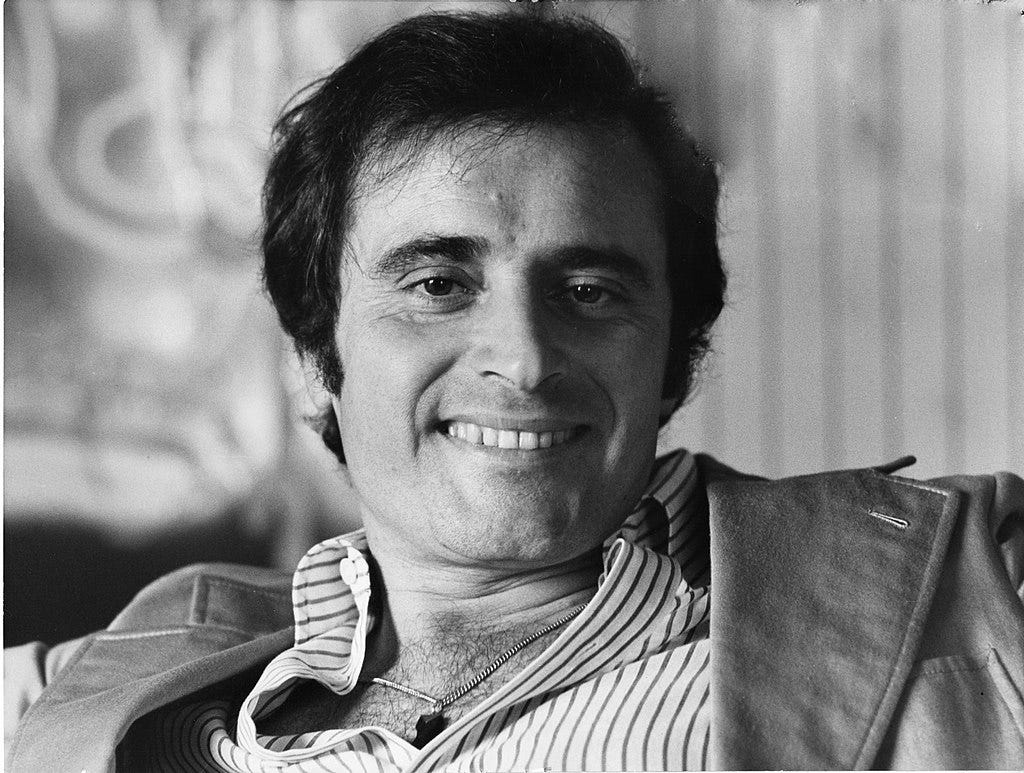

Unfortunately, not all music played at these events is remotely bearable. Oscar Peterson at the Savoy it ain’t. Instead, you get local bands whose singers sometimes possess only a tenuous grasp on pitch. You get DJs with no sense of volume or proportion. Or music. And you get old altercockers like beloved national treasure Edoardo Vianello, 84, whose hit song, I Watussi, is the single most offensive thing I’ve ever heard. In it, he uses the words “altissimi negri,” which means the same thing in Italian as it does in English (altissimi = tall; negri = exactly what you think it means). The song, written in 1963, is about how tall the Watusi tribesmen are.

Could Vianello have changed the lyric from negri to the far-less-offensive neri? Yes. Did he? No. Did damn near everyone in Amelia come out to hear him sing last night? Yes. Were they offended? Not likely, and the over-forties don’t get what the big deal is anyway.

Just to give you an idea:

To be fair, Vianello didn’t personally create this cartoon, but he did write the song that inspired it. It is, perhaps, the general indifference to the racism that I find appalling, although by Vianello’s own admission, the word negri was acceptable use when he wrote the song 58 years ago. Ordinarily, I would never dream of imposing my values on a different culture, but we are talking about an entire swath of human beings who suffer enormous amounts of prejudice.

I may have my opinions, but make no mistake, Italians have the mic.

I’ve become adept at deafening my ears to less welcome noises and opening my heart to the joyous ones. The month of August is one endless parade here in Amelia and in many villages across Italy. I love the processionals, the tradition, the history, the color. Without Covid restrictions, Amelia was able to hold its Palio dei Colombi, or Tournament of Doves, a two-week celebration of its medieval history. All five contrade or boroughs competed for prizes. Our contrada, Crux Burgi won the overall, I’m proud to say. All summer long, I could hear them practicing—a noise I was happy to listen to.

Here are a few of my favorites.

The Assumption of the Virgin was yesterday, accompanied by church bells.

And the Palio dei Colombi itself, complete with trumpets and flag bearers.

As you have heard me say more than once here at Cappuccino, Italy is life squared. No, squared and unshaven. She doesn’t care what you like. You accept Italy on her terms, or not at all.

She’s eternal. We’re just passing through.

Copyright © 2022 Stacey Eskelin

I always want to hear your thoughts! Feel free to leave any comments below.

Lovely, Stacey. Your ever-articulate piece took me back to several noise-focused memories of some contrast.

We were living in Parioli (Roma) in 1970. Our apartment overlooked the Olympic Village and the Corso di Francia, a busy, four-lane divided stradale that stretched from the base of our hill across the Tevere. During the legendary final match between Italia and Brasil in the World Cup, we listened to the entire game sitting on our terrazzo. There was no need for radio or television. We could clearly follow the progress of the match based on the cheers or groans (a-ooooo! ma-dai!) rising up from the apartment blocks below. It was noisy, but what fun! At the end of the game, when there was no doubt that Brasil had bested the Italian national squad, there was absolute silence... for about five minutes... then, the neighborhood erupted with horns, fireworks, joyous shouting and many flag-waving celebrants racing back and forth across the Corso di Francia on their "macchine" (the two-stroke Japanese bikes with their ear-splitting whines were particularly annoying). Rather than quietly suffer a national defeat on the world stage, all of Rome decided to celebrate second place. The citywide party lasted until the wee hours.

Some 49 years later, living in Richmond 30 miles southwest of Houston, after 24 hours of Hurricane Harvey's howling wind and horizontal deluge, the storm passed through leaving us gasping and stranded. The Brazos River had flooded into the ranch and farmland between us and the southwesternmost suburbs of the city. The flood plains of west Houston spilled over into the low-lying neighborhoods all along Buffalo Bayou. Freeways and surface streets were under water. We were totally cut off from everywhere and everything. After the initial chainsaw symphony of clearing driveways and yards of downed trees, our town fell into an uneasy silence that underscored how isolated we truly were. No cars on the roads, no sirens, no trains rumbling across the trestles. No power for radios or televisions or air conditioners. Our herd of cats, once allowed outside after the violence of the storm, skittered around the patio, bellies to the ground, ears twitching with "something's not right" demeanor. Even birdsong and the hiss of insect life was missing. I'd always thought that the phrase "a deafening silence" was a silly oxymoron and the height of hyperbole.

Although I prefer to work in quiet (no music, no radio or tv blathering in the background), I find the complete absence of sound threatening... as if the world around me is holding its collective breath... waiting for the other cataclysmic shoe to drop. I now equate total silence with impending doom.

There is noise and there is rhythm - noise jangles because it doesn't fit your mood; rhythm is something that fits, that you join. You've captured the rhythm of Italian life perfectly - that rhythm is culture, something that our polyglot, multi-cultural mish mash doesn't really have.

But having said that, there are a couple of components of Italian life we experienced, albeit in the province of Campania -- and each town and region has their own unique cultural characteristics -- that we could never get used to.

First, the fireworks -- PTSD inducing explosions that occur at any time of the day or night accompanied by huge clouds of smoke celebrating births or chasing away demons.

The other more serious issue was open burning of (mostly) agricultural waste - our town was surrounded by vineyards, chestnut and hazelnut groves which were kept in pristine condition by raking and burning leaves, branches, etc. If it was one isolated pillar of smoke, it wouldn't be an issue but for several months of each year, roads were obscured, and mountain sides looked like wildfires which is hard for someone who grew up in the western USA to see. Forget about breathing, if you had any kind of respiratory issue, it was exacerbated to the nth degree.

We assimilated and became family to our Italian friends but our dog never got over the fireworks and we make sure we don't visit during burn season -- the only (for the most part) discordant notes in our Italian life's symphony.