It Was The Deadliest Natural Disaster in American History

And were it not for greed, hubris, and stupidity, much of the disaster could have been averted.

Trigger warning: the following contains graphic descriptions of actual events.

Before the word “boi” meant a non-binary, transmasculine youth, it stood for B.O.I., Born on [the] Island, in this case Galveston Island, a thirty-mile-long, three-mile-wide strip of land that sits about fifty miles south of Houston, Texas. How you answered the question of whether you were B.O.I. determined how Galvestonians looked at you, did (or did not) do business with you, or in some instances, whether they invited you into their homes. At the turn of the second to last century, being a native Galvestonian was a very big deal, an automatic entrée into the wealthiest Texas families of the Gilded Age.

Galveston was in her heyday then, home to thirty-five churches, thirty hotels, four-hundred-and-eighty-four saloons, and perhaps most tellingly, fifty brothels. Sin always prospers. About 45,000 people lived on the island—seven thousand fewer than in its sister city of Houston—but it boasted the biggest opera house in Texas, and because of its status as the “Wall Street of the Southwest,” enjoyed far greater prosperity than anywhere else in the state.

There were three ruling families, the Kempners, the Moodys, and the Sealys. The eldest son of the Kempners, a man named Isaac Herbert, went on to found Imperial Sugar, proving, of course, that while the poor get poorer, money begets more money.

Much of that wealth was generated by the stranglehold these ruling families had on the port of Galveston itself. Before Houston dredged its waterways to create a port of its own in 1914, all freight went through Galveston, where it then connected with Houston’s railways. Seventy percent of the nation’s cotton was unloaded on Galveston’s docks, a distinction it still holds today.

But Galveston’s hegemonic control over Southeastern shipping came to an abrupt and tragic end on September 8, 1900.

As a barrier island, Galveston was accustomed to seasonal hurricanes. It sat only nine feet above sea level at the time, but thus far, no lasting damage had been done. Storms came, spent their fury on Galveston’s coast, maybe flooded the streets with an inch or two of water, and then boiled back out to sea. At one point, a breakwater or sea wall had been proposed, but Isaac Cline, chief meteorologist in the Galveston office of the U.S. Weather Bureau, dismissed as ridiculous the idea that the city even needed one. “Galveston can never be destroyed,” he insisted. “Our shallow sandbar makes it impossible for any wave to gather enough momentum to do significant damage.”

On Tuesday, September 4, 1900, Cline and his brother, Joseph, received a telegraph saying that a powerful storm was moving across Cuba. The Cline brothers checked the barometer, but so far the pressure was holding steady. The winds were calm, the heat sweltering, even for the end of summer. No one had any idea that a Category 4 storm was barreling toward them.

They might have known had they bothered to check with the Cubans, who tended to be annoyingly right about these things. In a fit of xenophobic pique, the U.S. Meteorological Office in Washington, D.C. cut off all contact with Cuba, which left the Clines and others like them at the mercy of their own blunted understanding of the weather.

Four days later, on Saturday, September 8, Joseph Cline woke with a feeling of impending doom. He roused his brother, Isaac, and in the dark, they stumbled down to the beach. “Winds are out of the north,” Isaac said. “A strong north wind always pushes waves back out to the sea. My guess is that the storm will tire itself out before changing course.”

By the next morning, the streets of Galveston were flooded a few inches, but delighted children were out early, splashing and playing. Just a few hours later, massive waves started pounding the beach, and the sand dunes simply disappeared.

When the Clines went to check the rain gauge, they discovered that the wind had ripped it away.

Now, the streets were angry rivers. The wind howled and moaned and wubbered. Joseph and Isaac returned to the house where Mrs. Isaac Cline, then pregnant, their three daughters, and about twenty neighbors who had taken refuge with them, waited with frightened eyes. Only now did the barometer plummet, reaching its lowest ever historic reading on land: 28.3 inches.

Night fell. When Isaac stuck his head out of the window, he watched the water rise four feet in four seconds. The waters of the bay had met the waters of the Gulf, creating a raging sea illuminated by jagged forks of lightning. The storm surge combined with the action of the waves created a battering ram effect, sending a 1000-foot-long railroad trestle smashing into the Cline house, knocking it off its foundation. Joseph grabbed the two older girls and threw himself into the torrent where they clung to a floating piano. Isaac held his wife, Cora Mae, and their youngest daughter. but poor Cora Mae, encumbered by her pregnancy, was pulled under the water and lost. Half of the neighbors who had sheltered with them were gone as well.

House after house was swept off its foundations and sent careening. In the dark, no one could tell what was grabbing at them from beneath the water. Terrified horses, mooing cows, turtles, cats, dogs, debris and dead bodies streamed past. The eerie flickering light betrayed an unimaginable hellscape. The body of a woman raced by, her head mutilated where a chandelier had caught hold of her hair and scalped her. Families were huddled on top of their slate-shingled roofs until even the roofs sank, casting everyone into the water.

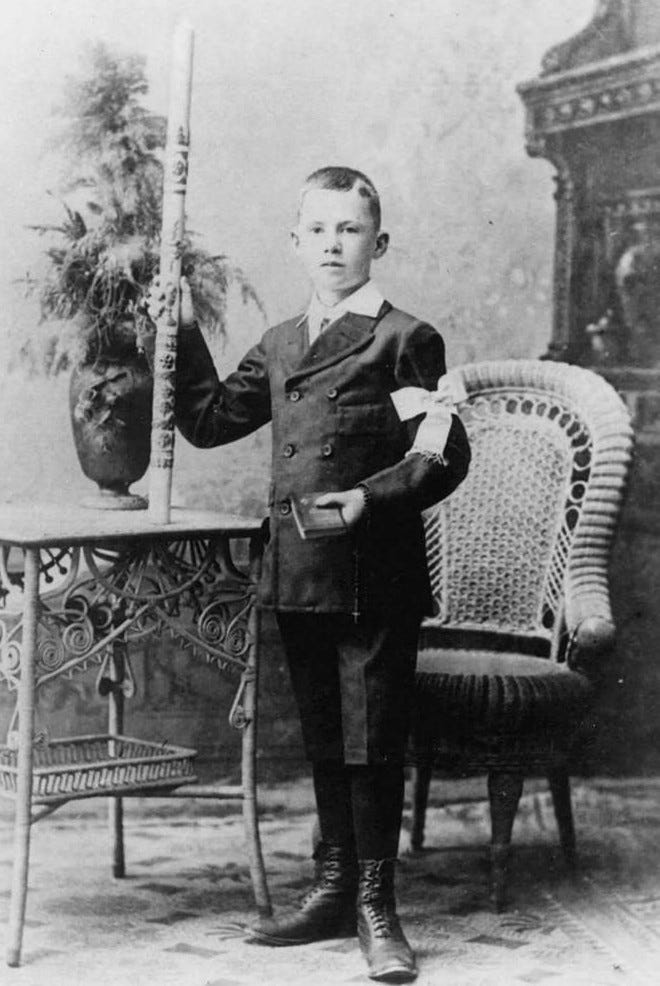

At St. Mary’s Orphanage, ten nuns tending to ninety-three orphans, instructed the nervous children to sing Queen of the Waves while they used a clothes line to tether six to eight children to each nun, for fear of losing them. One of the orphans was William Bernard Murney, born in 1887, whose mother had recently died of tuberculosis and whose father the very next day dropped dead of a heart attack. No sooner were the nuns finished when an enormous ship smashed into their beachfront building. The roof caved in. They were trapped. William clung to his eight-year-old brother, but was knocked unconscious by a beam, his brother lost to him forever.

The next morning, William and two other boys woke up in a tree. All ten nuns and ninety orphans were gone.

A midwife tending to a patient in labor kept moving the poor woman from floor to floor as the water rose. She dared not leave her, and there was no one else in the house to help. At around 3:00 a.m., both mother and child died, a not uncommon occurrence then, and the midwife was now faced with her own impending doom. She took a pair of scissors, cut off her hair, stripped naked, and flung herself into the howling torrent just as the house groaned and burst apart.

A few blocks over, one enterprising family took an axe to their bottom floor, hoping that by letting in water, the weight might stabilize their house. Their hunch proved correct, and the house was saved.

Eventually, all that detritus was pushed northward, forming its own breakwater, thereby saving those parts of the city. But during that endless shrieking night, between 8,000-12,000 souls perished, victims of the most horrific death known to man, short of fire.

Sunday, September 9, dawned, mild and blue. Over 3,500 houses were destroyed, and thousands more badly damaged. Entire blocks had been swept clean.

Unlike the proverbial Phoenix, Galveston would never rise again, not as she once was.

Now came the gut-wrenching, thankless job of disposing of the dead. At first, the bodies were piled high on barges, sailed out to sea, and then dumped. But the current brought the dead back quickly, and in even worse condition. Black male Galvestonians were conscripted at gunpoint to bury the remains. Anyone who dared to refuse was shot dead on the spot. Rather than getting killed, they would volunteer to help, but many fainted from the horror of what they saw.

The authorities had no choice then but to dispense with funeral rites. Bodies were burnt where they were found, and for weeks, the putrid smell of charred flesh hung like a pall over the island. Many soon realized they were burning their own parents or cousins or sisters. Ghouls descended on the beach to steal jewelry from the dead, sometimes tearing off ears to collect a pair of earrings or pulling off fingers to seize a ring. Men were shot for robbing the dead, but their desperation was great, and it was impossible to stop an entire horde of graverobbers, especially when there were no actual graves.

Galveston attempted to rebound with the fierce determination that has come to characterize Texas. Within just a few weeks, they had their telegraphs up and running. The air rang with the sounds of new construction. In 1902, Galveston finally erected the sea wall that might have saved them: 17 feet tall, 5 feet at the top, and 16 feet wide at the base. It stretched for three miles, cost 1.5 million dollars, and proved to be a feat of impressive (and lasting) engineering, since its curved surface forced waves back onto themselves.

The town council didn’t stop there. At the same time that the sea wall was underway, they dredged 16 million cubic yards of sand and mud from the Gulf and raised the entire level of the city. For months, dead sea creatures hoovered up by the vacuum equipment perfumed the air of Galveston, turning the existing heat and humidity into a jambalaya of rotting seafood.

But their plans worked. Galveston continues to hold out against increasingly frequent weather systems that every year threaten to destroy it. Now, a nuclear power plant sits not far down the coast and considerable agricultural runoff pours into the muddy brown water of Galveston, but Spring Breakers throng its beaches annually in the eternal, drunken Bacchanal of youth.

Will Galveston survive a future of rising sea levels and rapacious developers making the same stupid mistakes that left the city vulnerable more than a century ago? Not a man among us knows.

But I, for one, will leave the B.O.I.ers to their island “paradise.” I’m too old for keg parties and too young to remember the long-ago salad days of Galveston, but I can honor the dead with this remembrance of the hell they suffered on September 8, 1900.

Do you have any historical anecdotes of the hurricane of 1900 to add to this Cappuccino? Please leave your thoughts and comments below.

That area seems to invite catastrophes. Although it was technically Texas City, it was still Galveston harbor, where a ship with ammonium nitrate fertilizers exploded in 1947. Supposedly the largest non-nuclear explosion in history.

Galveston is one of the few places in Texas I actually miss. I worked for Progressive Insurance for 10 years and for several of those years was a member of their National Catastrophe Team. I was sent back to Houston in 2008 after Hurricane Ike. Most of the city of Houston was without power, which made getting anywhere in the city a nightmare. Every intersection on Westheimer was a go-for-broke clusterfuck.

I spent a couple days down on the Bolivar Peninsula, where several people died when they refused to evacuate. Of the approximately 500 houses on the peninsula, ONE remained standing. Houses had been swept off their concrete pads and taken out to sea by the storm surge. Cars had been deposited in some cases a half-mile inland in deep, thick mud.

Driving over the causeway to Galveston, the first thing I noticed was the pungent aroma of rotting garbage. Virtually every house on the island had piled everything they owned on their curb, soaked as it was in seawater from the storm surge. Those piles would remain in place for weeks.

Then there were the more remote places like Oak Island in Trinity Bay that looked like Ground Zero and did for weeks because they didn't have the money or the insurance to rebuild.

I saw sailboats in fields and on roads and damage I can't even begin to describe. I've lived and worked in two war zones, and yet I've never seen the sort of devastation I saw after Hurricane Ike.

If I live to 105 and never see anything like that again, I'll die a very happy man.