If You Think Social Media is Bad, Wait Until You're Trapped Inside the Metaverse

In our quest to take a vacation from reality, we are completely losing touch with it.

When I stop to consider where we are headed as a global society, I am filled with dread—gut-sick with it—a feeling that is compounded tenfold because I have kids. With any luck, I will shuffle off this mortal coil long before things get more serious than they already are, but it is likely my kids won’t. My kids and yours will face the environmental Armageddon we have failed to avert, one that is already well underway: glaciers the size of Manhattan calving in Western Greenland, warming oceans that spawn cataclysmic hurricanes, rising sea levels swamping coastal neighborhoods, higher global temperatures, droughts, famines, and the shifting migration patterns that are a result of famine—migration that overwhelms local populations and leads to the election of anti-immigration authoritarian governments. Italy’s, for example.

You might be surprised then to hear me inveighing against something as comparatively “harmless” as the metaverse. With disaster looming, why waste time quibbling about a glitchy new technology that amounts to little more than Virtual Reality 1.0?

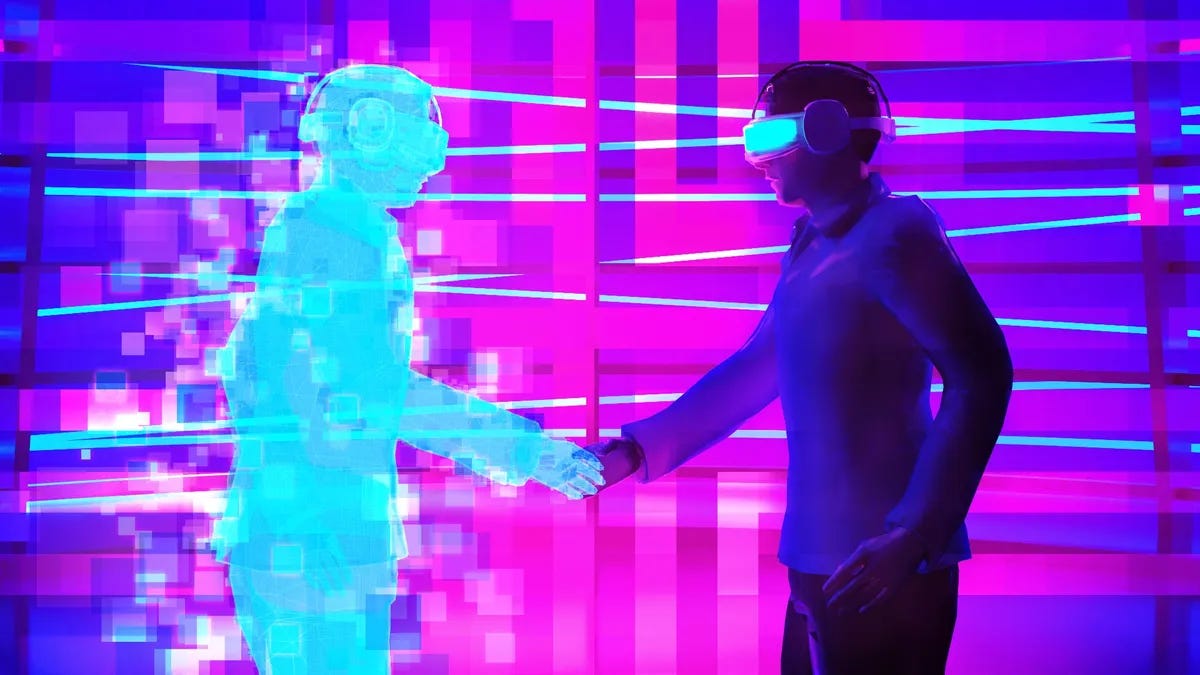

If the Internet is something we browse while theoretically retaining a sense of self, then the metaverse is an iteration of the Internet without it, an immersive virtual world facilitated by the use of augmented reality headsets. In other words, you snap on a pair of goggles, grab a pair of controllers, and then present a cartoon version of yourself to others who are hanging out in the same digital environments, such as gardens, theaters, comedy clubs, and mansions. Instead of picking up your smartphone, texting a friend, and agreeing to meet at a movie theater, you put on a pair of glasses and attend the movie together virtually. It’s better than real life, see? No sticky floors, overpriced popcorn, or lines.

But you aren’t you in any real sense. You’re you at a remove. In fact, you can pretend to be anyone or anything you want to be.

That, I fear, is part of the problem.

#

Neal Stephenson’s 1992 cyberpunk, anarcho-capitalist, science-fiction novel, Snow Crash, takes place in a Los Angeles of the near future. Its protagonist, Hiro, is a pizza deliveryman who lives in a storage unit after a worldwide economic collapse. In what was arguably the first use of the word “metaverse,” Hiro tries to escape his horrific conditions by donning a pair of goggles and entering a computer-generated world where he wages battle with a virus that infects the language center of the human brain.

The book itself is frighteningly prescient, albeit clunky, long-winded, and lacking in character development. It is also completely without hope. But apparently Facebook (now Meta) CEO Mark Zuckerberg, whose vision of the metaverse was entirely shaped by Snow Crash, must have missed the nuance.

As of this writing, Zuckerberg has sunk $10 billion into developing his flagship virtual-reality technology, Horizon Worlds, which is so disappointing and buggy, he’s decided to shut it down for the rest of the year so it can be retooled.

“Our devices are still built around apps, not people,” Zuckerberg recently complained at a developer conference. “The experiences we’re allowed to build and use are more tightly controlled than ever. And high taxes on new creative ideas are stifling. This is not the way that we were meant to use technology.”

Ah, Mr. Zuckerberg. Neither was failing to stem the tide of misinformation that led to Donald Trump’s election as president of the United States, more misinformation that gave us one of the lowest vaccination rates of any western democracy, and one criminal investigation after another, most having to do with harvesting our information without our consent. Also, if I may take a moment to translate his meta-message (see what I did there?), it is this: Zuckerberg doesn’t like the limitations placed on him by the government or by corporations like Apple. He benefits greatly from collecting people’s information without their knowledge or consent and plans on doing so indefinitely. He also wants to build something that isn’t dependent upon the smartphone.

Meta’s business model has always been to acquire its way to success. That’s how it got Instagram ($1 billion in cash and stock). That’s how it got WhatsApp ($19 billion). And that’s likely how Meta will dig itself out of the research-and-development hole they now find themselves in. Someone else will do it better. Meta will eat them.

Zuckerberg is the same fratty tech-bro whose motto, written on the non-virtual walls of Facebook’s headquarters, is “Move fast and break things.” A pity that the thing Zuckerberg has broken is democracy itself. Next up: reality. He’s going to bend it to his will. In fact, he will stop at nothing to accomplish this goal, which, in his mind, will return him to his former pristine status as the adorable wunderkind who “connected the world,” instead of the sweaty, Sunday suit, booster-seat boy who faced a Congressional panel of dinosaurs too old to croak out a relevant question.

Of course, Silicon Valley has always been bro culture. The video game industry has now surpassed sports or films in annual revenue; 68% of male Gen Zers consider gaming to be an essential part of their identity. Only one in seven of those gamers is female; indeed, sexism is even more alive in the Incel-scented world of gaming than it is in corporate boardrooms. Most computer geeks relate to machines better than they do to women; that which is seen as alien and frightening (women) is most often objectified.

Zuckerberg’s metaverse would like you to believe you are safe within its digital walls. After all, it’s not you but your avatar you are presenting. But in reality, that is hardly the case. There are an alarming number of reports from women who say they were propositioned, groped, or even ejaculated upon by other avatars. According to the nonprofit Center for Countering Digital Hate, harassment, assaults, bullying, and hate speech run rampant in virtual worlds and in virtual games—on average once every seven minutes. Worse, there are few mechanisms in place for reporting the behavior.

Many players of virtual games wear haptic vests that relay sensations to the player. Having another player grope you virtually feels just like the real thing. And while haptic vests of increasing sophistication will surely find their way into adult entertainment, in other venues, they become a vehicle for abuse. This is especially problematic when children enter the metaverse.

Meta claims it wants “almost Disney levels of safety,” but if history is any guide, that statement is disingenuous at best. Meta resists all attempts to control it. Moreover, abusive behavior is difficult to track in the real-time metaverse, and that is especially true for children who don’t always have the awareness to know what’s going on. In these augmented realities, children as young as six are interacting with adults pretending to be someone they’re not. A child-sized avatar with Pippi Longstocking braids, an adorable cat wearing a bow tie, or a dancing hippo can easily be the skin of a child predator. No one would ever know.

That’s just one element of the dark side of social media, which the metaverse will only exacerbate. Mental health problems among children, adolescents, and young adults have been on the rise since the advent of social media. Meta knew its photo-sharing app, Instagram, was leading to eating disorders and self-esteem issues among young women; it did nothing about it. And it’s not going to lift a finger to protect children in the metaverse either. It can’t. Without government regulations and protections, children are left to the vagaries of crypto-capitalists like Zuckerberg, a man who has made it abundantly clear that people are to be exploited for personal gain.

The trouble with progress is that it usually comes with enormous hidden costs. Cars, for instance. Cars led to suburban sprawl, the rise of malevolent oil kingdoms like Saudi Arabia, a welter of freeways that slice through neighborhoods, choking pollution, Putin, fracking, and seven out of ten of the biggest international conglomerations that are oil-dependent.

Was this progress?

When the first televisions arrived, experts said that television was harmless entertainment. It isn’t. Television is little more than a means of stove-piping ads directly into your home. When the main driver of the U.S. economy is consumer spending, whetting your appetite for consumer goods becomes a “moral” imperative. Never mind that advertising must, by its very nature, find fault with who you are and what you look like in order to “fix” the problem with its advertised product.

Progress?

Then came social media, of which we just now grasping the broader social cost. Not only is “reality” digitally distorted by heavy filters, it has become more or less irrelevant. What better precursor for the complete shattering of reality presented to us by the metaverse?

There was a time in human evolution when fire was a new technology. It warmed our bodies and cooked our food. It kept predators at bay. But without “regulation,” fire could quickly grow out of control, leveling entire forests.

I strongly feel that’s where we’re at now.

Dystopian writers Aldous Huxley (Brave New World) and George Orwell (1984) had differing visions of the future. In Orwell’s totalitarian reality, we were spied on and manipulated by screens; in Huxley’s, we amused ourselves to death. Pleasure was engineered by games like centrifugal bumble-puppy and feelies, a cinema of sensation that bears an eerie similarity to the metaverse. But on one thing both writers agreed: Man has a pressing urge to escape reality, especially when reality becomes too much to bear.

Reality is messy, expensive, occasionally horrifying. It’s the world we know through our senses, one that more or less conforms to our ideals of what’s consensually “real.” But if we recreate reality with technology like that offered to us by the metaverse, what repercussions will that have? Is any money other than a handful of underfunded academic studies being allocated to examine what ramifications this technology will have on us? Or are we just going to “wing it,” like we always do, damn the consequences?

As our real world crumbles at our feet, we create ourselves another. Our digital avatars will never age, never get fat, never die.

But there’s another word for that kind of break from reality.

It’s called psychosis.

Copyright © 2022 Stacey Eskelin

What are your thoughts? I read each and every one of them, so be sure to chime in. There’s a comments section below.

Wow. A lot to digest here and I don't disagree with any of it. I am choosing to be "interested" in what unfolds in front of us, because any of the other work I come up with is going to end me in an asylum.

"There are an alarming number of reports from women who say they were propositioned, groped, or even ejaculated upon by other avatars."

I feel embarrassed to be a Penis-American. My compatriots are pigs and immature children who don't know how to treat women with even virtual respect. How pathetic is that? Mother must be SO fucking proud.

In the '60s, it was "Reality is for people who can't handle drugs." Today, the only thing that's changed is the drug of choice. And I fear today's drug of choice is far worse.