If You Don't Know Padre Pio, You Don't Know Italy

Don't bother coming over till you can answer a few simple questions.

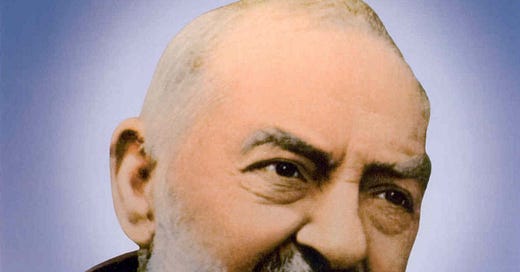

As a Italian Franciscan Capuchin, friar, priest, saint, stigmatist and mystic, he is one of the most beloved figures in the Catholic world—of greater importance to the Italian faithful, perhaps, than Christ or the Virgin Mary. A medallion of him wearing his signature fingerless gloves dangles from a million Catholic key fobs. His likeness hangs above doors, inside restaurants and throughout hospital corridors. Statues of him sit, gnome-like, along garden paths and preside over parking lots.

His name is a Padre Pio, the most celebrated of Catholic saints, and if you’ve never heard of him, grab your rosary, you’re in for a ride.

In the interests of full disclosure: I am not a religious woman, nor do I have an axe to grind with those that are. In my universe, everyone is invited to worship whatever gods they choose to, so long as they don’t proselytize, insist their god is superior to my agnosticism, impose their religious beliefs on my right to choose—or deny me the right to exist as a member of society invested with the same privileges as a man. I don’t want radically religious people on my schoolboard, in the White House, or on the Supreme Court, but I encourage people of all reasonable faiths to seek positions of leadership if they hold sacred the notion that church and state must remain forever separate.

That’s the caveat emptor. Here’s the story.

Separation of church and state is a concept as foreign to Italians as fettuccine alfredo. There is no fettuccine alfredo here. Okay, maybe two restaurants serve something called fettucine alfredo, but fettuccine alfredo is an entirely American construct. Despite this holy—or unholy—alliance, non-separation works okay in Italy. That’s because everybody is Catholic, at least culturally.

Many Italians do treat their faith casually, however. Come Sunday, church pews are mostly empty. The confessional gathers dust. But if you innocently point out the existence of a cross, say, inside an elementary school classroom where Muslim children also attend, they will crisply remind you that you are American and have no idea what the Catholic faith means to Italians. If you’re wise, you will nod vigorously while sidling out the door.

All this to say that the purpose of this article is not to depose idols; rather to introduce an American audience to the most revered of all Italian Catholic saints, and to acquaint them with certain particulars of Padre Pio’s hagiography that might raise a few eyebrows among the faithful.

I’m here to report; not to judge.

Francesco Forgione (the man later known as Padre Pio) was born on May 25, 1887, to peasant farmers in the Benevento region of Southern Italy. From an early age, he professed a desire to enter the priesthood, and his devoutly religious parents were only too happy to indulge that wish. But young Francesco needed more than three years of education to qualify, so his father, Grazio Forgione, emigrated to the United States in search of work to pay for it.

On the 6th of January, 1903, at the age of fifteen, young Francesco entered the novitiate. On January 22, he took the habit along with the name of Fra (Friar) Pio, and the simple vows of obedience, chastity, and poverty.

Despite suffering fainting spells, migraines, poor appetite, and exhaustion, Padre Pio was ordained a priest in 1910. Already there were rumors of him falling into stupors or “ecstasies.” One friar proclaimed that he’d seen Padre Pio levitating off the ground. Whether these miracles actually occurred or not is perhaps less important than the fact that Italy was on the brink of World War I, about to experience devastating losses with the Spanish flu, and the faithful needed a miracle. It is said there are no atheists in foxholes, but after months of senseless slaughter, I doubt there are too many faithful there either.

His constant refrain was “Pray, hope, and don’t worry. Worry is useless. God is merciful and will hear your prayer.” Many of the faithful traveled great distances to visit him in his monastery at San Giovanni Rotondo, outside Benevento, where he’d become their symbol of hope in a war-ravaged land.

Padre Pio was fifteen when the stigmata allegedly first appeared, weeping wounds said to correspond to those left on Christ’s body during the Crucifixion. They went away, but in 1918, while hearing confession, he reported their mysterious return. The stigmata were to stay with him for the next fifty years until his death on 23 September, 1968, and these wildly controversial marks of Christ’s favor are still being studied today.

Were they real or were they the result of purposeful deceit? Father Agostino Gemelli, an educated physician and psychologist and contemporary of Padre Pio’s who studied the stigmata personally, dismissed the priest as an “ignorant and self-mutilating psychopath who exploited people's credulity … Anyone with experience in forensic medicine, and above all in the variety of sores and wounds that soldiers inflicted upon themselves during the war, can have no doubt that these were wounds of erosion caused by the use of a caustic substance.”

But recently, the real rubber met the road when acclaimed historian Sergio Luzzatto was granted unprecedented access to the Vatican archives and discovered an incriminating letter from Padre Pio himself. In 1919, the monk dispatched a female cousin to the neighborhood pharmacy, requesting secrecy for the delivery of carbolic acid, a chemical substance capable of causing sores in human flesh. Padre Pio later said it was needed to sterilize syringes, but there had long been reports of finding bottles of carbolic acid in his cell.

Is is little wonder then that two successive popes regarded Padre Pio not only as a lunatic, but a fraud?

By the 1920s, a worldly (and potentially embarrassed) Vatican forbade him to say Mass in public, bless people, or hear confession. Yet, their attempts to relocate him to another convent in northern Italy were met by such mass rioting, they left him where he was. This miniscule Capuchin monastery was a leading place of pilgrimage in Europe by this point, a local economy on its own. Even today, the town of San Giovanni Rotondo abounds in dry cleaners, restaurants, car garages, hotels, coffee bars, and jewelry stores, all bearing the name of Padre Pio.

I doubt the armies of hell or a Vatican’s worth of debunkers will dissuade the faithful from believing in the miracles of Padre Pio.

It is said he was out gathering chestnuts in a nearby forest one day, put them into a bag, and then sent the bag to his Aunt Daria. The woman ate the chestnuts and saved the bag as a souvenir, placing it inside a kitchen drawer next to her husband’s store of gunpowder. A few nights later, using a candle to see by, Daria looked for something inside the drawer and accidentally ignited the gunpowder, which set fire to her face. She took the bag Padre Pio sent and placed it over her burned skin. Immediately, her pain disappeared, and no burn or mark was visible. Was this miracle ever investigated? Of course not. The faithful don’t require such proofs.

In 1971, three years after Padre Pio’s death, the Vatican reconsidered its position and opened an investigation into whether he deserved to be canonized. The investigation did not address the subject of his stigmata, mysteriously, and ignored secret tapes of him confessing to multiple instances of carnal relations with local women. The Vatican’s investigation was—for the friar’s followers, at least—a mere formality. In their minds, he was already a saint. And the miracles kept coming. In 2002, a statue of Padre Pio in Messina, Sicily, is said to have wept blood. His crypt remains a place of enormous veneration, which you can see here. There are dozens of Padre Pio live streams of his remains, including Padre Pio Radio and Padre Pio TV.

In the end, whether Padre Pio faked his stigmata, had unfortunate fascist associations, or enjoyed unspeakable congress with “two women per week” matters less than the love and support of the people that follow him. Isn’t the tendency to mistake the messenger for the message one of our greatest human failings? We want to believe—and some of us do—but we are quick to forget that the person we believe in is just as susceptible to temptation and human frailty as we are. We bestow the virtues of Christ on an ordinary human being, discover his feet are clay, and then cynically denounce all idols as charlatans.

Love him or hate him, Padre Pio is a twentieth-century legend. We ignore what he represents at our peril. Not because of who he was, but because of what he means to millions of people worldwide, who believe magic and the supernatural exist in the modern world.

Perhaps it is up to us to make that ultimate leap of faith, which is forgiveness for those who trespass upon our sense of logic and credulity. Or, on the other hand, we could just close our eyes, hold our nose, and jump.

Do you have any Padre Pio stories or observations on religious faith? If so, I wanna hear ‘em. Leave your comments below.

As an atheist, it's easy to reject stories like those of Padre Pio as self-serving bullshit. And yet, millions believe it- some because they legitimately believe, some because their faith is that important to them, and some because...well, what's that other option? It all seems rather harmless.

In the case of Padre Pio, there's probably no downside in believing in his holiness. Sure, he almost certainly was a charlatan, a fraud, and a womanizer...but what harm, really, was done to Italy? Some folks need something to believe in, and if something like this gives them hope...well, there are worse things.

It's not like a bunch of ignorant rednecks elevated a reality-show gimcrack to a god-like cult status and then elected him President.

Stacey, I venerate some of the Christian saints. One of my favorite saints is Saint Francis. I prefer St. Francis to Padre Pio, in the Historical Saints of Italy category.

Yesterday was St. Francis' feast day. Two nights ago, I posted a joke meme about how the Patron Saint of copying people on email is St. Francis of A CC. I did not know it was the anniversary of his death in 1226. He died so late in the day that the Vatican chose to honor him on October 4th. On the timeline, I also posted my two favorite works of art depicting St. Francis, the one by Bellini at the Frick in NYC, and the Giotto at the Louvre of St. Francis receiving the stigmata.

The church could not ignore St. Francis' insistence that the poor and that animals deserved better from humans because of the stigmata. The church fathers in their satin and lace would have much preferred to declare him a heretic, but the stigmata were conclusive: he was a saint.

So I am not surprised if Padre Pio did indeed fake his stigmata. Carbolic acid is still painful, although not as painful as nails all the way through.

I love St. Francis so much that I went to Assisi on one of my trips to Italy when I was a young woman, partly to see the incredible Giottos there. I loved it there, and would like to return.

I don't think it was at all accidental that I had a post up about St. Francis as his feast day dawned. Call it a happy coincidence. In general, I venerate female saints more than male ones, with a few exceptions like St. Francis, St. Michael, and St. Expedite.

I suggest you look up the Giotto in the Louvre online. Giotto was born slightly more than six decades after St. Francis, which is almost contemporaneous compared to the centuries between St. Francis and us. His painting is glorious, and my favorite part: Jesus is shown with the Many Wings formation sometimes seen in older Christian icons of saints. Lines are drawn showing the stigmata flowing from Jesus in the sky with many wings down to St. Francis' hands and feet.

It kind of looks like Jesus is a kite........ and St. Francis is flying him.