How to Talk About Art Vandalism vs. Removing Confederate Monuments

Here are the differences between these two acts of vital social protest

Ten days ago, two climate activists from Just Stop Oil, a coalition of groups working to protest government insufficiency in tackling climate change, hurled yellow gruel at Van Gogh’s most famous painting, “Sunflowers.” Afterwards, they glued their hands to the wall beneath the painting in the National Gallery, shouting, “What’s worth more? Art or life?”

Days before, Just Stop Oil activists glued themselves to the frame of an early copy of Leonardo da Vinci's "The Last Supper" at London's Royal Academy of Arts, and then to John Constable's "The Hay Wain" in the National Gallery, all sacred icons of western culture.

Three days ago in Potsdam, Germany, two climate activists flung mashed potatoes at Claude Monet’s 130-year-old masterpiece, “Les Meules” and then glued themselves to the wall beneath it. The pair was from Letzte Generation—German for “last generation”—and they’d come to protest public and institutional indifference to those suffering from the effects of climate change. “People are starving, people are freezing, people are dying,” one of them shouted. “We are in a climate catastrophe. All you’re afraid of is mashed potatoes on a painting. Do you know what I’m afraid of? Scientists tell us that we won’t be able to feed our families in 2050. Does it take mashed potatoes on a painting to make you listen?”

Look, it’s a compelling argument. And I know first hand the rush and the challenge of speaking truth to power. I was an early member of Occupy Wall Street in Houston, Texas, as corporate a town as you will ever find. At one of our biggest marches, S.W.A.T. hovered their helicopters right above us so we couldn’t hold the rally without bullhorns. An officer in full gear pointed a bolt-action sniper rifle directly at me for the crime of peaceful assembly. Later, many of us were arrested.

I say this in the interests of full disclosure—in the epic struggle between David and Goliath, my sympathies are almost always with David.

It is worth noting that none of the paintings in question was materially damaged. They are protected by sturdy frames and glass covers. Still, it’s hard for me to feel okay with these attacks, and I’ve spent the past two weeks asking myself why. Have I simply gotten to an age where that kind of drastic action by young people seems like hooliganism—a curmudgeonly “you kids get off my lawn” dynamic? Do I value art above human life (it’s possible I do, although without humans, there is no art)? Does their obvious bid for attention put my back up (attention seeking always feels cringey to me)? Or are my hackles raised by the idea that these protesters are attacking an artwork that can’t fight back? Is it the bully/victim optics of the thing that are forcing me to view their actions as misguided?

The urgency and importance of what they’re fighting for, of course, is undeniable. I weep when I think about what they’re up against. What we are all up against.

There is no denying anymore that we are in a climate emergency. Any emergency requires immediate action. When 11,000 scientists from 153 countries sign a report to signal their agreement that the world is facing catastrophe, the time to worry is now.

There’s more carbon dioxide in our atmosphere than at any other time in human history.

Arctic sea ice is melting at an astonishing rate, raising sea levels and devastating coastal communities.

The number of floods and heavy rains has quadrupled since 1980 and doubled since 2004.

Average wildlife populations have dropped by 60% in just over 40 years.

Dengue fever, a mosquito-borne virus, will likely spread throughout much of the southeastern U.S. by 2050. More viruses will follow.

Those are facts. We must face them. And governments the world over are responding too slowly or not at all. It makes sense that young people hope to force our fractured attention spans to the issue by hurling tomato soup at priceless masterworks. As far as the cause goes, I’m 100% onboard.

But I’m not convinced they’re going about this in the best way.

Just Stop Oil and its brethren betray a woeful ignorance of human nature; such antics won’t draw attention to the cause, which is hard for most people to grasp anyway (i.e., it rained today; therefore, climate change doesn’t exist). It will only draw attention to the vandalism. For the same reasons the Reverend Martin Luther King abjured acts of violence, climate protesters might consider the violence done to our national psyches when we see soup dripping down our most beloved works of art, Van Gogh’s in particular.

“Van Gogh cared deeply for nature, and for humanity,” Jennifer Leach from Reading, Berkshire, writes. “He was a missionary before he became a painter. He was poor, he lived simply, and his passion was to reveal the extraordinary beauty of nature to those who could not see it. For his magnificent gift to humanity to become a target for environmentalists is a violation of all that the painting upholds.”

Did anyone ask Van Gogh if he wanted this?

This is why targeting a cultural masterpiece like “Sunflowers” feels a bit like turning on your own kind. It’s different than splashing red paint on the windows of Goldman Sachs or occupying a government building or a national landmark like the Statue of Liberty. In a world where nothing feels sacred anymore, to desecrate one of the few things we collectively revere comes across as tone-deaf—although hardly without precedent.

The practice of attacking artwork as an act of political protest has a fascinating yet troubling history. In 1964, members of the anti-authoritarian Situationist Movement actually decapitated a statue of the Little Mermaid in Copenhagen. You are doubtlessly familiar with the mermaid in question. She is a beloved Danish icon who gazes forlornly over the sea. Unfortunately, she has suffered multiple indignities: twice, she’s been beheaded, once her arm was hacksawed off, and in 2003, the poor thing was discovered floating facedown in the harbor after someone blew her up. To add injury to insult, a Danish politician tried posting a photo of the statue on Facebook where it was promptly removed. Why? Facebook said the statue violated its nudity rules.

We humans are nothing if not ridiculous.

In 1974, a woman took a can of spray paint to the Mona Lisa in protest of a Tokyo gallery’s lack of disabled access. In 2013, four Fathers4Justice members vandalized two paintings with spray paint and glue, one in London’s National Gallery and one at Westminster Abbey. Their reasons? Nothing so dramatic as climate change. They merely wanted their kids back.

But the most notorious art vandals were, surprisingly, the British suffragettes. In 1914, a woman named Anne Hunt (also known as Margaret Gibb) smuggled a meat cleaver under her clothes and slashed a portrait of Scottish essayist Thomas Carlyle by the Victorian painter Sir John Everett Millais.

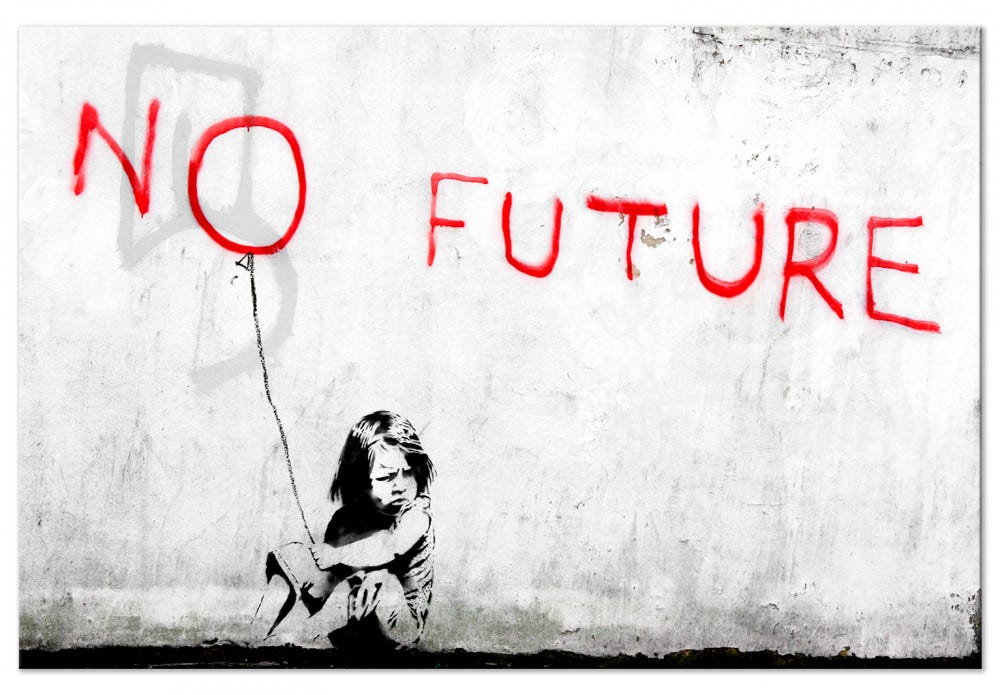

Hunt was arrested and sentenced to six months in jail. At her trial, she argued that the artwork would now be “of added value and of great historical importance because it had been honored by the attention of a militant.” When you consider what Banksy’s shredded Girl with Balloon is now worth, you can’t help but be impressed by Hunt’s uncanny ability to predict the future.

Earlier that year, a suffragette and former fine arts’ student named Mary Richardson smuggled a meat cleaver into the National Gallery (meat cleavers appear to be the suffragettes’ weapon of choice) and slashed a painting by Diego Velázquez called the Rokeby Venus to protest the imprisonment of Emmeline Pankhurst, another activist suffragette. In a further act of political vandalism, a “young and stylishly gowned suffragette” took a hatchet to three paintings and also a guard at the Dore Gallery on New Bond Street. She caused severe injury to the man and destroyed a priceless engraving by the Italian artist Francesco Bartolozzi.

Sadly, her sister-in-arms, Mary Richardson, went on to become a disciple of fascist Oswald Mosley.

How then is art vandalism for climate crisis any different than the removal of Confederate war statues from public spaces? Is there a difference?

I believe there is.

The vast majority of Confederate War statues aren’t “art.” They were erected during the Jim Crow Era, 1877-1964. Their existence is an affront to the United States since these bronze “heroes” of the Confederacy were meant to re-enforce white supremacy and memorialize a treasonous government whose very foundation was built around the perpetuation of Black slavery. Their purpose is to intimidate and alienate Black Americans. They are the opposite of what it means to be a patriot.

Such semiotic totems belong in a museum, not a public space. They are to be studied, not revered. Nor are they to be protected as sacred. Their self-appointed champions are antisemitic white supremacists, neo-Confederates, neofascists, Klansmen, and far-right militias. Eleanor Harvey, a senior curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum and Civil War scholar said it best: “If white nationalists and neo-Nazis are now claiming this as part of their heritage, they have essentially co-opted those images and those statues beyond any capacity to neutralize them again.”

Even so, these statues mustn’t be destroyed. They are a part of our history, ugly as it is. But they do need to be removed from the public sphere.

No one should be forced to behold the agents of their own enslavement.

Notice how I proposed these symbols of slavery and oppression be relegated to museums. Museums must remain safe spaces where we observe with understanding and perhaps a certain amount of healthy detachment the text of our cultural history. But they mustn’t be ground zero for a climate activism that’s starting to feel like brutality toward a beloved grandparent.

That said, even though I don’t agree with their methods, I support Just Stop Oil and other climactivist organizations. We’re at that point now. We can’t afford to be precious. But at a certain point, it is likely that all museum paintings will be removed or put behind glass—which I agree is not as calamitous as our climate emergency itself, but is still another wound, another wall, another remove.

But then, who cares what climativism looks like? Who cares what their motives are? We are already in the throes of catastrophe.

I hate to say it, but it may not even matter what we do at this point.

We may already be too late.

Copyright © 2022 Stacey Eskelin

I love when you share your thoughts here on Cappuccino. Chime in, please, using the comments section below.

Ruining precious art that belongs to all of us has no link to climate change. I am very concerned about climate change and I am doing all I can to prevent the further perpetuation of climate change. Destroy art isn’t going to reduce sea levels one inch, it’s just going to piss people off and the only way we can solve this problem is working together.

The thing about art is that it belongs to all of us, no matter who owns it. When the Taliban blew up those Buddhas in Afghanistan, that erased any and all sympathy I might ever have had or will have for them. It mattered to me that Notre Dame burned down. There are things on this planet that are just beautiful - precious few. They belong to all 8 billion of us. 2 or 3 people shouldn't be using them for their own ends no matter what they are advocating for. Yes, it gets them attention but it makes me, gay liberal tree hugging, whale loving anti-nuke me, want them gone - no matter what they are fighting for. Find another way. You're smarter than that. And if you aren't then please just go away.