He Rocked the Book World by Stealing Unpublished Manuscripts

And he's from my adoptive hometown of Amelia

In the years between 2016-2022, dozens of celebrity authors, including Margaret Atwood, the estate of Stieg Larsson, Sally Rooney, and the actor Ethan Hawke, along with hundreds of unpublished writers, found themselves on unlikely common ground: all were victims or near-victims of a scam artist who grifted them out of manuscripts.

At first, the thief’s phishing schemes remained undetected. Posing as a literary agent, a book publisher, or a literary scout (representatives that scour the U.S. book market for titles that might do well translated into other languages or made into movies), he solicited unpublished manuscripts using methods that are at once clumsy and brilliant. He ginned up fake email addresses with subtly rearranged domain names: @penguinrandormhouse.com as opposed to @penguinrandomhouse.com is the example cited by the New York Times. Then, posing as an agent or editor, say, he could feign interest in a writer’s work, ask to see a manuscript, and disappear into cyberspace.

As a writer myself of half a dozen published books, I can assure you this is no victimless crime. A writer spends, on average, ten years in apprenticeship, learning how to craft stories that might be worthy of publication. A full-length novel usually takes a year to write, sometimes longer, and has often been equated to gestating a human fetus. Manuscripts are products of love, labor, and in many cases, mental anguish. To have one snatched from you by fraudulent means must feel like the grossest kind of betrayal.

Over a span of five-plus years, the thief clearly gave little thought to the psychological repercussions of what he was doing—moreover, no one knew why he was doing it. None of the pilfered manuscripts appeared on the Dark Web. No ransoms were demanded. No spoilers to popular novels were leaked. And no novels appeared in any language that might have been Frankensteined out of other writers’ work. He registered over 300 domain names, some paid for with stolen credit cards, all with the intention of swindling authors out of their blood, sweat, and tears.

“Follow the money,” a friend of mine told me. “He’s obviously working on behalf of a foreign publisher. Somebody’s gotta be paying him. Maybe he’s using other people’s ideas to write screenplays that he can then option to movie producers.”

But I’m not convinced money was his motive. For me, his true motives were revealed in this excerpt from an exceptional, must-read article that recently appeared in The Vulture:

In 2019, the thief found out that Eka Kurniawan, an Indonesian novelist who was nominated for the Man Booker International Prize, had a deadline looming and decided to impersonate his agent. “You told me the manuscript would be ready before the 18th of July and it’s now the 14th,” the thief wrote, applying pressure on Kurniawan to hand over the draft. Kurniawan is now two years late, and his agent, Maria Cardona, said the stress was partly responsible. “He’s been quite stuck,” she said.

Clearly, there is only one reason to hector a prize-worthy author in such a way. It wasn’t money he sought. It was power. The power to change skins and wear borrowed authority. The power to coerce people out of something of enormous value to them. And the dark thrill of “getting away with it.”

His persistent efforts to phish for manuscripts sent shockwaves throughout the book world. Everyone grew paranoid, even in an industry that had long guarded its secrets. Translators working on one of Dan Brown’s sequels to his bestselling The Da Vinci Code, for instance, were forced to work in a windowless basement under the surveillance of security guards. Even trips to the bathroom were noted. Name-brand authors were now writing on computers with no Internet connection and then dispatching their four-hundred-page manuscripts by mail. Nobody wanted to fall victim to the stealer of writers’ souls.

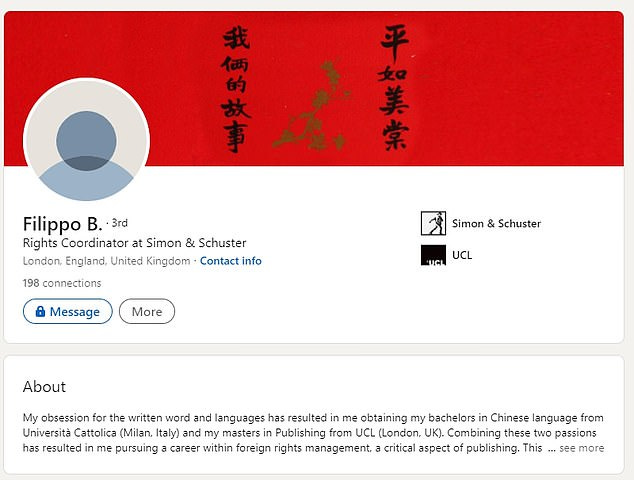

Then on Wednesday, January 5th, 2022, the Federal Bureau of Investigation arrested Italian national Filippo Bernardini, a twenty-nine-year-old rights coordinator at Simon & Schuster’s London division. I was at home in Amelia at the time—an obscure Umbrian village about 100 kilometers from Rome—when I saw the headline. I couldn’t believe it. Not two minutes later, I got a text from a smart, thoroughly bilingual, well-informed friend who wrote: “The manuscript thief is from Amelia.”

After that, I dove right down the research rabbit hole, pouncing on every bit of information I could find about Filippo Bernardini. Amelia encompasses both the centro storico (historic area) where we live and the periferia (surrounding area), with a population of maybe 12,000, only a fraction of which reside within Amelia’s ancient walls. The fact that the manuscript thief had grown up here hardly seemed possible. Nothing happens in Amelia. I like it for that reason.

Then, in a lightbulb-sur-la-tête moment, I remembered that our recent mayoral race boasted a candidate named Piero Bernardini. My smart friend confirmed that Piero, a local physician, is also Filippo’s father. Even that blew my mind. Piero ran on a platform of political Progressivism, but then fell out with his own kind and started a second party, which effectively split the vote. Umbria is hardly a bastion of liberalism to begin with, but a party divided against itself stood no chance against the conservative juggernaut of Laura Pernazza. She won handily, Piero went home, and a few months later, his son was arrested at JFK Airport for wire fraud and aggravated identity theft, compliments of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York.

His son, Filippo, was by eyewitness report a “weird kid.” This same contemporary who went to school with him (and chooses to remain anonymous) discloses that Filippo wrote a novella with himself as the protagonist wherein he is raped in the boys’ bathroom at school. Filippo’s father, Piero, was unusually strict with him, and since Filippo is gay and lives openly with his boyfriend in London, I wonder to what degree his orientation bothered his father. Two local sources describe Piero as “impiccio” (messy, potential trouble), buffoonish, and “not what he seems.” As a rule in Italy, especially the farther south you go, male homosexuality is frowned upon. Fortunately, younger Italians are far less bigoted, but even so, many gay Italian men are deeply in the closet.

I’m sure this was one of many reasons Filippo chose to live outside of Italy. And he is clearly a brilliant young man, fluent not only in English and Italian, but Mandarin Chinese. It’s hard to have ambition in Italy. Good jobs are scarce, the old guard refuses to retire, and the brain drain of Italian youth to other parts of Europe is a serious and ongoing problem. It’s not the defection I blame him for, but the emotional and psychological terrorism perpetrated against writers.

But for me, this is where the story takes an even more surprising turn. In my typically American way, I had assumed that Filippo would be persona non grata in his native Italy. He had done a crime, been caught, and now everyone would figuratively turn their backs on him. I couldn’t have been more wrong. Regional newspaper, the Corriere dell’Umbria, wrote an article that can only be described as wildly biased. “He never extorted a penny or threatened anyone,” the article reads, as though that somehow absolves him. They refer to him not as a thief, but a “collector of novels.”

Filippo Bernardini is out of jail now on an astonishing $300,000 bond posted by his boyfriend Ben Kaye. He was forced to surrender his passport, must wear an ankle monitor, and has to remain in New York City for the next two months. Kaye also surrendered his passport. Did the money actually come from Kaye? If not, from whom? Was Kaye aware of Filippo’s activities? I don’t know. Nobody knows. It adds layers to the mystery.

Something tells me we haven’t heard the last of Filippo Bernardini. And it wouldn’t surprise me to someday learn there’s a screenplay of his life. “The measure of a man is what he does with power,” Plato said. Filippo Bernardini abused his power. And now it is my hope that he will at long last suffer the consequences.

Have you been following this story? Do you have an opinion you’d like to share? Please leave your comments below.

Fascinating story!

Bernardini's actions don't meet the technical definition of plagiarism, since he never presented the work as his own. But it falls into the same pocket, in my book. A little over six years ago (Gods! That long now!) a friend and fellow academician asked me to write something about the subject, because other academics(!!) at his college were taking a sanguine view on the subject: "it isn't that bad," they were saying. Part of my response was the following:

"A comparison here might be with identity theft, because the thief is not only stealing my credit rating and bank accounts, but is effectively stealing *me*, in the form of my digital, or even public, persona."

Persons not intimately engaged in some form of creative pursuit might easily fail to understand how fundamentally *personal* it is, in that I have spent months or years pouring my *PERSON* into this work.

What I don't understand with the above case is how the authors and victims have lost their materials. When you email a document to someone, you still have that document in your possession. It is over 40 years since anyone was writing on a typewriter, so even when a paper MS is sent to someone, the original file remains on disk. Proving provenance can be a nightmare, even with date/time stamps on the file(s). But Bernardini evidently made no effort to claim the materials as his own, so provenance was never even challenged.

I still hope the arrogant fucker gets to learn why you never want to drop the soap in the shower.