Graffiti: Art on a Different Canvas?

“Graffiti is one of the few tools you have if you have almost nothing.” ~ Banksy

Society may see graffiti as a uniquely modern scourge, but people have been scribbling on public surfaces for centuries—plenty of phalluses, as you might imagine, but other forms of mural art proliferated in 1970s’ New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, Detroit, which then spread in a colorful diaspora all over the world. It became a flashpoint, pitting those who perceived graffiti as local folk art deserving of wider recognition against others who saw it as Black urban violence and decay. Because of these associations, graffiti has become a kind of shorthand for gang activity—and to be fair, some of it is used to define territory—but it is far more than that.

The first thing property developers do when repurposing abandoned, windowless factories into high-end lofts is scrub the “gallery of the people” from the walls. In many respects, these public spaces are the only canvas street artists have to express their thoughts on gentrification, economic inequality, the buzz of lust, the pain of heartbreak. As an illicit act, there is open defiance to it, which is one of the reasons graffiti and street art are viewed as a criminal threat, a decimator of property values, a sign that barbarians are at the gate.

Much of it is insider humor, street rivalries, cryptic allusions that few outsiders would understand. This, too, is the cant of the underworld—a world that’s largely invisible to commuters and high-end loft dwellers.

It is art made under pressure not to get caught.

The more aggressively municipal authorities work to erase graffiti from public walls, the fresher the canvas is for a new wave of street artists. The kick is the illegality of the act itself. More than a few taggers believe that if it’s not against the rules, it’s not graffiti—which explains why so many of them eschew public spaces freely offered to them. Where’s the fun in that?

Being a graffiti artist means accepting the impermanence of your own art. No matter how beautiful or visually arresting, it is only a matter of time before your work is destroyed by the city, eroded by weather, or painted over by another artist. The ubiquity of cell phone cameras has prolonged the life of specific pieces. Artists can, and do, take photos of their own and other people’s work, posting them to the archive of social media. In this age of digital reproduction, street artists can vastly increase and even monetize their fame as counterculture edgelords.

In 2009, two street artists orchestrated an illegal foray into a massive New York City subway station that had long sat unused. Fellow street artists were secretly escorted into the station to create one mural each in a single night. The Underbelly Project, now considered “an elusive pirate treasure of contemporary art”, demonstrates what’s possible when street artists organize. Their short video is well worth watching.

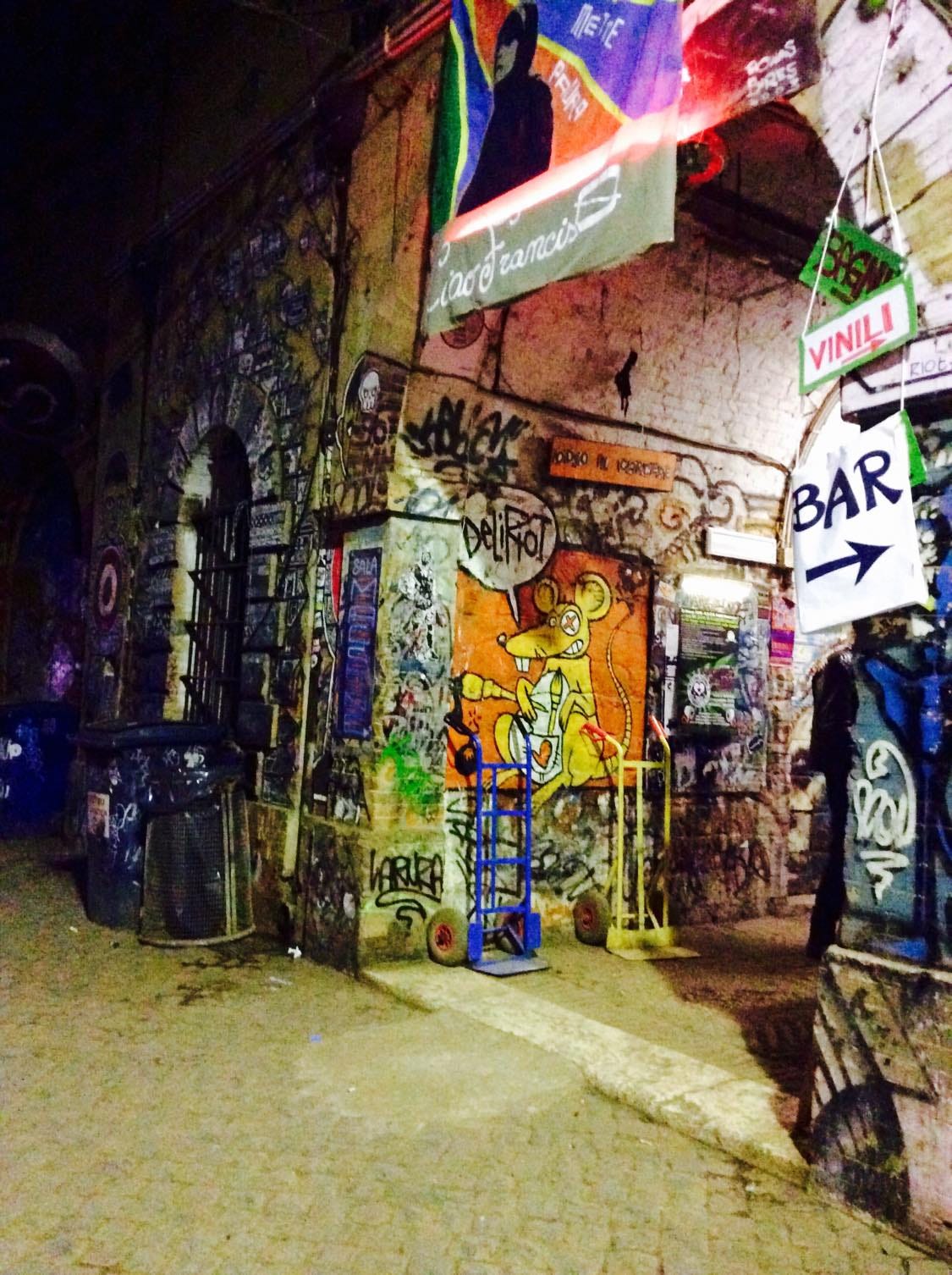

But the U.S. hardly has the market cornered on mesmerizing street murals. Italy has a storied tradition of occupied spaces—buildings and structures taken over by artists and lefty political radicals who, because of lax Italian squatting laws, are almost impossible to dislodge. Occasionally, SWAT teams will come in and reclaim a space, but many have been allowed to stand.

One of the finest examples of artists’ cultural centers is a derelict 19th-century fort in Rome called the Forte Prenestino. Once used as a dump by the Municipality of Rome, all thirteen hectares were officially occupied on May 1st, 1986. Since then, it has become an exhibition gallery, theatrical space, farmer’s market, classroom, cinema, tattoo and piercing studio, tea room, organic café, and a recording studio. It has no American equivalent, and is truly one of my favorite places to visit when I’m in Rome. The walls are a kaleidoscope of murals, and the crowd is laid-back without being obnoxiously hipster. The last event we attended there, pre-Covid, was an underground comics convention that was so packed, we could barely squeeze through.

The following video is in Italian, but will give you some idea of the sheer scope of Forte Prenestino.

It is not unreasonable to question why advertising is legal and graffiti is not, and there are those who fight that injustice. But I’m inclined to agree with the ones who believe the legalization of graffiti would also be its death knell.

There is a broken windows theory in criminology which posits that visible signs of anti-social behavior and civil disorder (e.g., graffiti and street art) create an urban environment conducive to more serious crime. The theory suggests that directing police to target crimes such as vandalism creates a safer city. This viewpoint is not without its detractors, however. Baltimore criminologist Ralph B. Taylor argues that petty crimes like vandalism don’t portend the intensification of criminal behavior; lack of economic opportunity does.

On private property, graffiti may rightly be considered vandalism, but in some public spaces, I feel it has a right to breathe. It is we who must come to terms with our own feelings about it. If it threatens us, why? Are we right to feel intimidated? Is there hate-speech involving swastikas or the persecution of any minority group? Is our immediate impulse one of despair—”Oh, there goes the neighborhood”?

I’m not sure there’s a one-size-fits-all answer. “A wall is a very big weapon,” famed street artist Banksy said. “It’s one of the nastiest things you can hit someone with.

“Art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable.”

I am sincerely interested in what you have to say on this subject. Feel free to leave your comments below.

“Art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable.”

I love that. Variations of it have been my mantra for longer than I care to remember. Comfort the afflicted; afflict the comfortable. Piss them off. Make them think. What, really, is so wrong with slapping someone in the face with an idea they'd normally reject out of hand?

I have a love/hate relationship with graffiti. Most of it is crap and serves only as eye pollution, but there are some very talented artists who do some great work. Perhaps the idea of doing something considered socially unacceptable is what moves them. Perhaps no one in the "art world" is willing to take them seriously and nurture their talent. Whatever the case, I think there's an argument to be made for the idea of graffiti as public art. I have no idea who will or how to curate it, but it's worth a look, no?

I love Forte Prenestino <3 and you are right, it is one of the best places to find authentic street art in Rome