Dutch Golden Age Painter Pieter de Hooch Exhibited a Deep Sensitivity to Women

His male gaze was personal, not just sensual, and here's why that's important.

Here at Cappuccino, we are dedicating this week to pushing back against the depressing banality of Internet culture. What that means exactly will be revealed in tomorrow’s edition, but for now, let us turn our attention away from cringeworthy stories about Instagram influencers renting studios made to look like private jets and get back to what’s real. What’s real is our first line of defense against status seeking, fake Instagram backdrops, mediocrity, and capitalist monoculture.

What’s real in this case is a 17th century Dutch Golden Age painter named Pieter de Hooch who you’ve probably never heard of. Not unlike his more famous contemporary, Johannes Vermeer, his biography is a bit thin; little is known about either artist. But for all intents and purposes, De Hooch and Vermeer ran true to type (Dutch = sensible, grounded; Italian = operatic, reactionary). Neither artist was prone to acts of flamboyant aggression (e.g. Caravaggio, who killed a man), and in fact, one of the very few details I can add here about de Hooch is that his father was a bricklayer and his mother was a midwife.

It is mother’s profession that stands out to me. Little Pieter likely accompanied her on her rounds, witnessing the births of many children. It is the tender intimacy, eye for detail, and warm familiarity that he brought into his paintings which make me think he had profound respect for women. While the Italians were painting Baroque allegories taken from Roman mythology and the Bible, de Hooch and his brethren were painting everyday scenes: households, church interiors, courtyards, and “merry company” of tipsy Dutchmen rollicking at the neighborhood tavern.

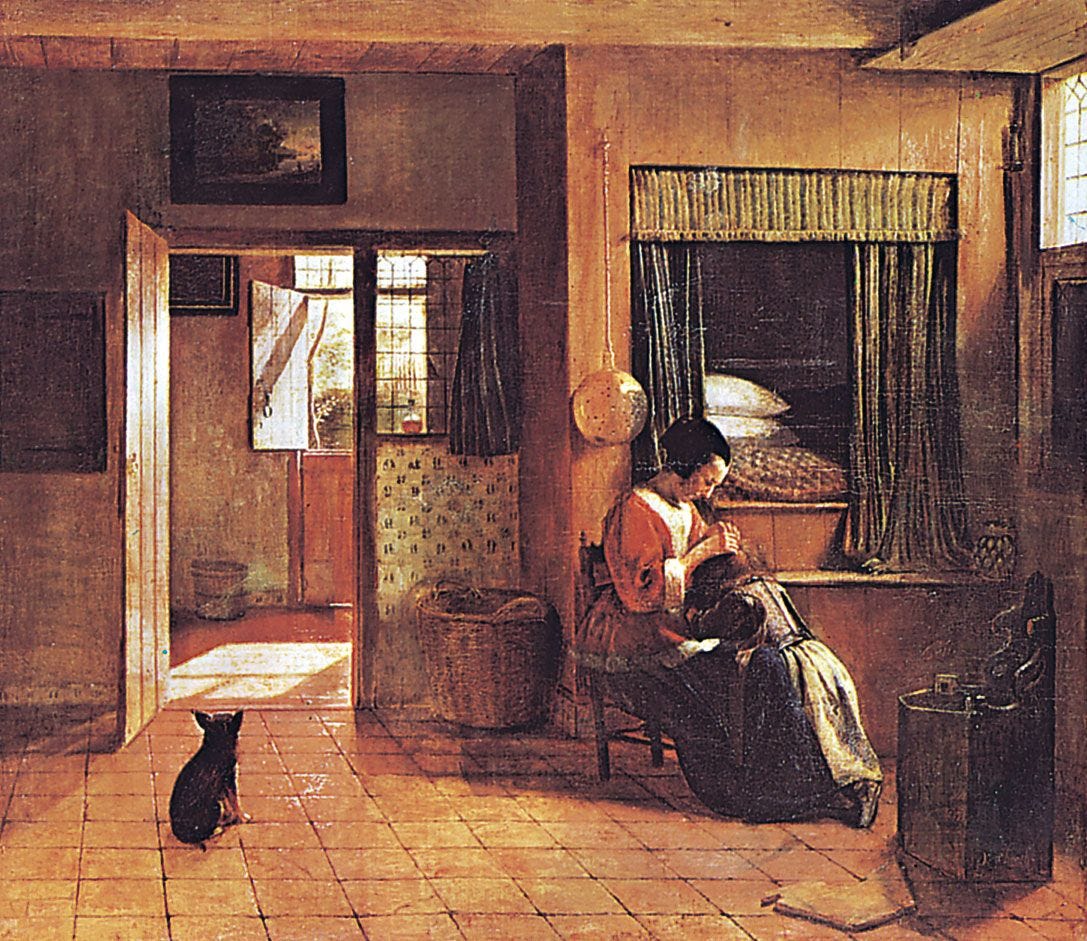

Consider then the quiet prosperity and hushed beauty of this painting of a sturdy Dutch woman breastfeeding her infant while her daughter plays with the family dog.

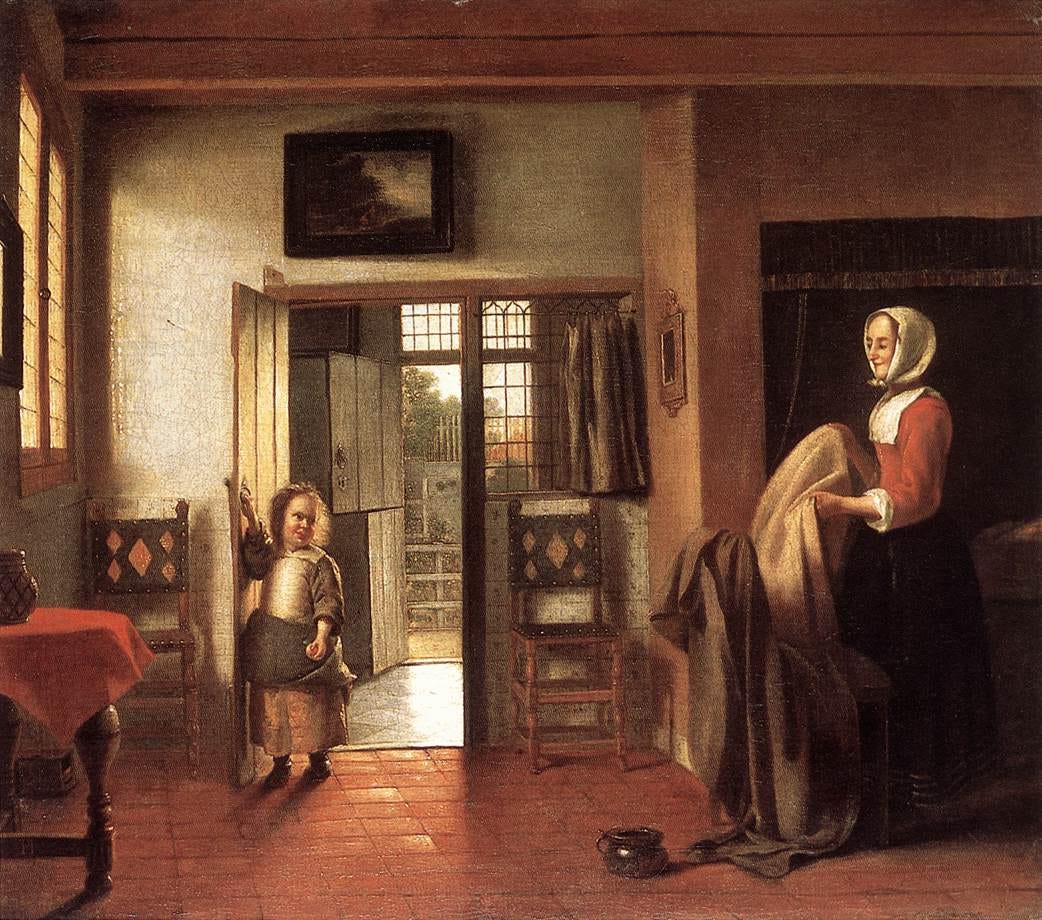

We know that in 1654, de Hooch married a woman named Jannetje van der Burch and had seven children with her. It is perhaps no coincidence that he turned even more of his attention to these scenes of serene, even idealized, domesticity. It is when de Hooch looks with his heart and not just his eyes that his work truly speaks to us across the centuries.

In brushwork and facial composition, Johannes Vermeer was undoubtedly de Hooch’s superior. De Hooch’s faces are sometimes a little wooden, and yet don’t they add to the overall lack of pretension? I believe de Hooch outdid Vermeer in delicate observation of light and real feeling for his subjects. Most of the children depicted in his works are female, mothers are forever attentive, and male figures are largely absent. Even the “props” in these domestic scenes tell a story. The bucket in Interior of a Dutch House, for instance. What is its semiotic value? Is de Hooch telling us that women, like water, are essential to life? Its position on the floor is no accident. De Hooch is clearly making a point.

It is the proletariat nature of the Dutch Golden Age that I find so irresistible. If ever a time machine were possible, it is the work of de Hooch and others that gives us a window into the world of the 17th century—paintings that are all the more remarkable for being secular instead of religious. Although strict Dutch Calvinism forbade the painting of religious subjects for display in churches (graven idols, and such), they were allowed to hang in homes. Yet even there, Dutch moderation prevailed. Few religious paintings were produced during this time.

For sheer output, the Dutch Golden Age painters have few rivals. Thousands of paintings were sold at weekly street fairs—a rough estimate of 1.3 million between the years of 1640-1660. Prices were affordable for everyone, which put some of the greatest artists of the period at terrible disadvantage. Vermeer, Rembrandt, and Frans Hals all died in penury. And war with France brought the Golden Age art market to its knees, a blow from which it never fully recovered. Still, a Englishman traveling through Holland in 1640 remarked that many blacksmiths and cobblers had “some picture or other by their forge … such is the general notion, inclination and delight that these country natives have to painting.”

For de Hooch, tragedy struck in 1667 when his wife, Jannetje, died. It is widely believed that the quality of his work began to decline after that. Until recently, it was assumed that his psychological deterioration was severe enough to land him in an asylum, but it was actually his son by the same name who died there. Although the exact date of de Hooch’s own death is unknown, it is doubtful he lived past the age of fifty-five, leaving behind an exquisite body of work that is never overly sentimental or pretentious, and shows us his love for women, domesticity, and family life.

Copyright © 2022 Stacey Eskelin

I want to hear your thoughts, so be sure to chime in below!

Excellent essay; very instructive.

If you haven't seen it, I highly recommend the wonderful film "Rembrandt's J'accuse" by Peter Greenaway. He methodically dissects the messages concealed in his famous painting The Night Watch, using forensic analysis, a college lecture format with his disembodied face, interviews, and live action recreations of real or imagined scenes. (There is also a companion film with a more strsightfoward dramatic narrative called Nightwatching.) Its a cinematic masteroiece

de Hooch's name and some of his work were already familiar to me, though I'd not anchored the connection between the two in my mind. So I both knew the name, and recognized several of the paintings, but didn't associate the one with the other.

I tend to think of Reubens as Dutch, though of course he was Flemish. In fairness, though, the distinction was not fully settled back then, as the 80 years war (the Dutch Rebellion from the Spanish empire) was still very much in vogue. (And "vogue" is the proper term. Every time they negotiated a treaty, the sudden drop in spending led to an economic depression, so they stirred up a hot war once again.) France inserted themselves occasionally in an effort to conquer the Brabant, but they didn't want the French there either and became Belgium instead.