Banksy: Subversive or Sellout?

Can you be worth 50 mill and still be considered a "street artist?"

I’m a firm believer that we don’t see the art, we see ourselves. Everything we look at, whether it’s the Mona Lisa or Jesus marinating in a glass tank of the artist’s own urine, we are looking at that work through the lens of our own perspective.

To illustrate my point, let’s deconstruct the work colloquially known as Piss Jesus. People were horrified when they saw it. There was so much gasping and pearl-clutching, the artist himself, Andres Serrano, felt compelled to issue a statement saying he’d been a Catholic all his life.

Senators Al D’Amato and Jesse Helms expressed the usual red-meat outrage, especially since Serrano had received National Endowment of the Arts’ funds. When I saw the photo, I thrilled to its transgressive nature, but also thought taking aim at religion was a little stale.

But that’s only my perspective. Again, we don’t see the art, we see ourselves.

Banksy’s work, I’ve never been ambivalent about. It speaks to my angry, quasi-anarchist nature. To me, Banksy and his forebear, Blek le Rat, are two of the finest graffiti artists the world has ever known. Banksy owes a huge debt of gratitude to Blek, the progenitor of stencil graffiti, a French street artist who’s been painting rats on the walls of Paris since 1981. He requisitioned Blek’s rats, used them darkly, satirically, subversively, and created a political and social dialogue that made Banksy (not Blek) a household name.

Banksy’s works have appeared on streets, walls, and bridges throughout the world, including the Gaza Strip. "Gaza is often described as 'the world's largest open air prison',” he wrote, “because no one is allowed to enter or leave. But that seems a bit unfair to prisons — they don't have their electricity and drinking water cut off randomly almost every day."

Graffiti is illegal, which is why Banksy prefers to do his work anonymously. No one even knew his true identity until 2008, when the British newspaper, The Mail On Sunday, outed him as Robin Gunningham, born on 28 July 1973, in a town near Bristol. Even now, he makes no public appearances without a mask.

As one of Bristol’s DryBreadZ Crew, Banksy was part of a thriving early 90’s underground scene that sprang up in response to mainstream clubs’ indifference to hip hop music. By occupying abandoned car parks and empty warehouses, multiethnic artists and musicians did what multiethnic artists and musicians usually do, which is create a creative subculture of social protest.

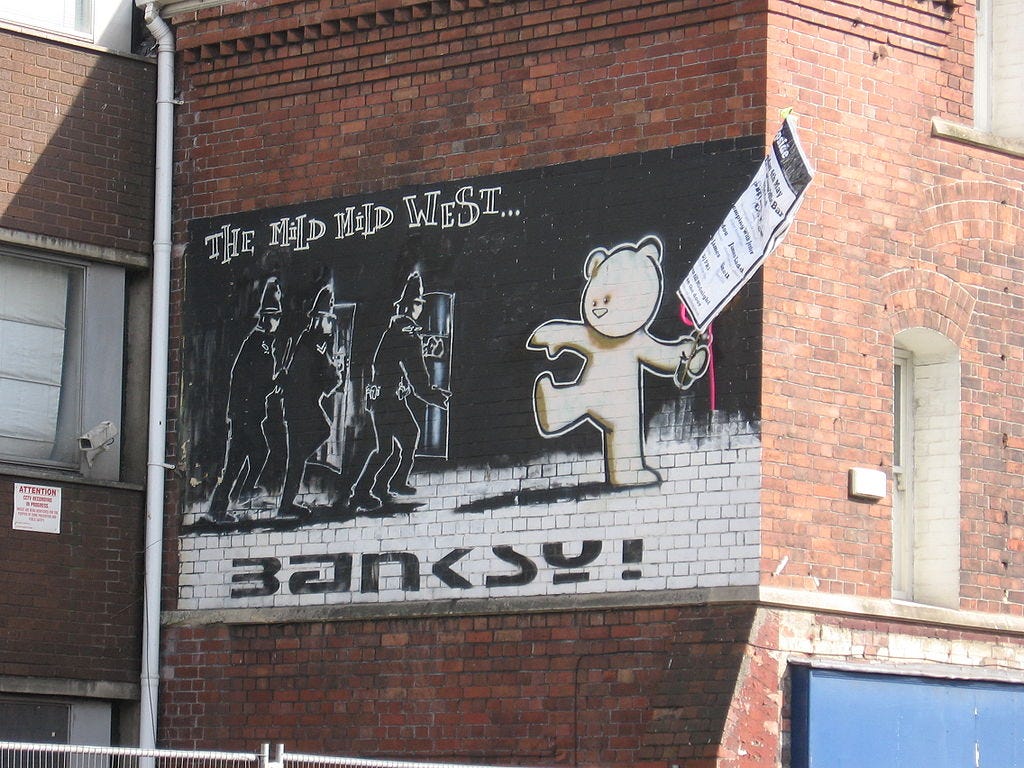

Banksy came out of this tradition, producing his first wall graffiti in 1997, The Mild Mild West, which depicted a teddy bear throwing a Molotov cocktail at three riot police. The Bristol underground had been receiving a lot of police harassment then, something Banksy wanted to address in a pointed yet peaceful way.

It didn’t take long for Banksy’s works to be noticed on structures across London and Bristol. All of them were, and are, anti-capitalist screeds, which is an important point to remember when, later in this article, I question the “street” credibility of an artist who is now worth 50 million dollars.

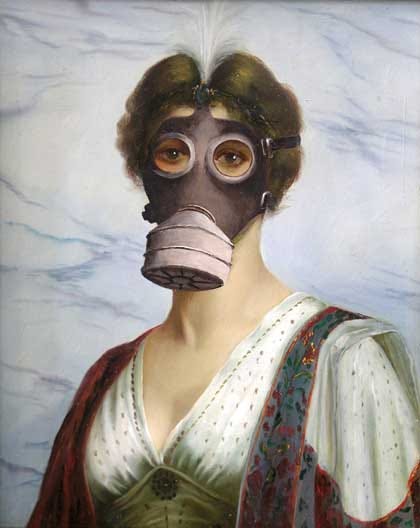

Because street art is, by its very nature, subject to human interference, this piece, Gorilla in a Pink Mask, which Banksy produced in 2002, was painted over by a Muslim cultural center. It was later restored, albeit poorly, and then the chunk of wall it had been stenciled on was removed. A similar occurrence happened in 2020 after Banksy stenciled Covid-infected rats on the London subway. His message: “If you don’t mask, you don’t get.”

Unfortunately, hours after Banksy posted a Instagram video of him tagging London’s Underground train, Transport for London had the work removed and then issued a spectacularly tone-deaf, condescending statement: “We would like to offer Banksy the chance to do a new version of his message for customers in a suitable location”

On 21 August 2015, in Somerset, England, Banksy organized a pop-up exhibition called Dismaland, billed as a “family theme park unsuitable for children”; also as “entry-level anarchism.”

Demand for tickets was astronomical.

I do find myself envying the succinctness with which Banksy’s installations are able to get his point across.

In what was arguably his most audacious stunt, Banksy disguised himself in a Professor Challenger beard and infiltrated the Brooklyn Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Natural History and MOMA, tacking up his own pieces on the same walls occupied by Old Masters:

Yet, Banksy also has his critics. First, there are those who rightly accuse him of appropriating the work of Blek le Rat, among them Blek himself. “It’s difficult to find a technique and style in art,” he said, “so when you have a style, and you see someone else is taking it and reproducing it, you don’t like that.” Others, especially New York street artists, dismiss Banksy’s work as “anarchy-lite.” Satirist Charlie Brooker has written that Banksy’s work “looks dazzlingly clever to idiots.”

If an artist is lucky, he gets older. Banksy is almost fifty now, married, and has clearly progressed to the next stage in life, which is making pots and pots of money. Ordinarily, this would be a desirable, even admirable thing. Banksy has dedicated himself to his work; he deserves to get paid.

But what does it mean when the same artist who’s been such a vocal opponent of the haves actually becomes one? Does it automatically revoke his right to inveigh against those who, like him, enjoy the fruits of capitalism? To me, it feels a little like Malcolm X putting on white face and buying a pair of chinos. I don’t want Banksy not to benefit from his work; I’m just not sure cashing in on your own press entitles you to street cred.

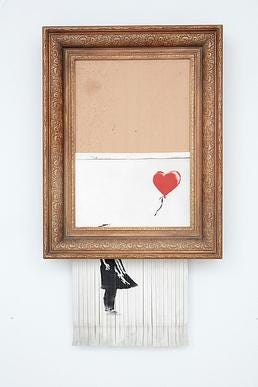

Ever the stuntsman, Banksy engineered an art world coup in 2018 when his most popular work, Balloon Girl, sold at Sotheby’s for £1.04m. Right after the gavel dropped, blades hidden inside the picture frame partially shredded the canvas.

You can easily imagine the press coverage this received. “The auction result will only propel this further,” an expert was quoted in the Evening Standard, “and given the media attention this stunt has received, the lucky buyer would see a great return on the £1.02M they paid last night … in its shredded state, we'd estimate Banksy has added at a minimum 50% to its value, possibly as high as being worth £2m+."

Surely, Banksy knew this act of “subversion” would enhance his value as an artist. Sotheby’s own denials of involvement ring equally hollow. Who was Banksy taking the piss out of—buyers who are gullible enough to pay millions of dollars for a piece of shredded canvas, greedy auction houses willing to exploit those buyers, or an adoring public who might not realize how, in one swoop, Banksy became the very thing he’d been telling everyone to despise?

It’s worth noting that Josh Gilbert, a sculptor and magician, conjectures that the original painting is rolled up in a hidden compartment in the back, and a pre-shredded copy ejected from the frame. In Banksy’s own video demonstrating how he constructed the apparatus, the cutting blades are placed sideways, which would have made it impossible to cut the canvas top to bottom. Perhaps, the testimony of an artist who has made a name for himself as a professional trickster is meant to be taken with a large grain of salt.

Now, Banksy has a London studio and does commissioned work, earning millions. He continues to stage critically hailed exhibitions, and has privately funded a rescue boat to save refugees in the Mediterranean Sea.

People evolve. Artists evolve. I, personally, go back and forth on the issue of Banksy having sold out. If he were any other kind of artist, it wouldn’t be an issue.

But can an artist worth 50 million dollars, however well-intentioned, still be a man of the people? Or does the white-hot spotlight of fame burn everything it touches?

To get more information on Banksy, I strongly recommend you watch this fascinating video about his work and the work of other street artists.

I’m really eager to get your hot-take on this subject. Leave comments!

Copyright © 2022 Stacey Eskelin

HAS Banksy "sold out?" Or did he, as all of us inevitably do, evolve? While being a starving artist may be noble, it also sucks. Financial success is hardly a bad thing, but does it render an artist less "relevant?" Does he/she lose their voice once they become famous/wealthy?

Some artists sell out- Jeff Koons is the most disgusting example that leaps immediately to mind. I think Banksy at least still has a sense of the place of his art in the world. As you said, he's now married, middle-aged, and has moved on to a new stage in life. It happens to all of us if we're fortunate to live long enough. The key is what you do with that. Koons blatantly sold out. Banksy? I don't think you can say that about him.

Good art is subversive. It pisses people off, or at the very least makes people think. It makes "the authorities" react and demonstrate their cluelessness. I think that ultimately will be Banksy's legacy. As much as I hate graffiti, there are a few artists out there whose work deserves a wider audience. Without Banksy, I think many doors would still be shut.

Banksy's been fortunate enough to reach a place where no matter what he does, he makes bank. To some that brings his credibility into question, to others it increases his credibility. Damned if you do, damned it you don't. I suppose the key is to not give a damn.

Some 40+ years ago, on one of my visits to Westwood (the tony neighborhood that UCLA calls home) there was an artist doing a chalk "painting" on the sidewalk. It was stunningly beautiful, poignantly so, given its obviously transitory nature. 25 -- 30 years ago when I was living in Chicago, the city basically gave a stretch of wall around a cemetery under the Red Line elevated over to street artists. They created this lovely mural that ran for upwards of 50 yards. It took a very long time for it to be degraded by standard issue tagging by the local gangs; it was treated as more or less off limits.

Just thinking of some of the street art I've personally encountered, not including some of the musicians who were busking on the corner.

The question that comes to my mind reads something like this: After the first million, what does the person do with their newly acquired fame and wealth? Does that money just go to their newly established off-shore tax shelter, or do they turn around and start giving back to the community? It becomes a question of "virtue", though perhaps the Greek αρετή (ar-eh-Tay) might be better here, so as to avoid the connotations of the English word.

For the Greeks, αρετή was about "living well," εὐδαιμονία ("eudaimonia"), a word which, inexplicably, is often translated as "happiness." What utter twaddle; eudaimonia literally means "healthy spirit." To live with αρετή was to have a healthy spirit, and that meant living in balance with your world. Such balance, as Aristotle went to great lengths to argue, was context dependent; it was a "mean" between two vicious (from the word "vice") extremes of excess and deficiency. Such a virtuous mean is different for a poor person as compared to a wealthy one. Poor people should be generous, neither miserly nor extravagant with their limited resources.

But wealthy people, to be virtuous, must be "Magnificent" (Aristotle's term.) They must do things on a truly grand scale that gives back to their community which has, after all, made their wealth possible in the first place.

Which brings me back to Banksy: what is he doing with his wealth? Is he establishing a community outreach system for artists in the ghetto? A school that serves the under represented? Or just a bigger house, with a bigger pool, and a bigger garage sheltering a faster car? Answer those questions, and you'll answer whether or not he's a sellout.

(By the bye, both Nobel laureate economists Amartya Sen and Joseph Stiglitz are explicitly Aristotelian in their approaches to economics. Rather than just asking, Has wealth increased?, they ask, Has eudaimonia increased? Are a few people richer, or have the possibilities for the many expanded into greater reaches of living well? So all that Greek philosophy stuff is not just a bunch of addle pated hand waving. It has significant, real world applications.