A Look Back: Ida B. Wells, a Woman Who Changed the World

If you choose not to vote today, you are betraying everything she fought for.

Today, Americans are voting in one of the most consequential midterm elections in American history. In theory, we are voting for government representatives that reflect our respective belief systems, whether those beliefs support a woman’s right to choose or how to address our looming climate catastrophe. But in fact, we are voting for more than that—more than delivering an electoral referendum on the incumbent president, which is what we typically do during a midterm.

We’re voting on the future of America.

Once you get past the noise, this year’s midterms are about race and what it means to be an American. Sure, this strange new breed of climate-and-election-denying Trumpublican will go on and on about the economy and being “fiscally responsible,” but actual facts are not on their side. Reagan tripled the national debt after decades of Democratic administrations had finished paying it off. Bush doubled that debt, and Trump increased it by 33% in just four years, despite having inherited a relatively strong economy from Obama.

These deficits came from tax cuts for the wealthy, of course. Cutting taxes on the richest Americans is pure red-meat Republicanism. “Trickle down” economics and all. When the top 1% earns 27% of the nation’s wealth—more than the combined total of the entire middle class—that comes to a whole lot of scratch.

Republicans sure talk a good game though, don’t they? They’re the “fiscally responsible party,” the self-proclaimed defenders of free speech and democracy. And yet, none of their actions supports this narrative. Republicans are the ones spearheading suppression efforts to remove the word “gay” from school curricula. They’re the ones opposed to critical race theory, an academic study of stark racial disparities that have persisted despite decades of civil rights reforms. Critical race theory has been around since the ‘80s. It was an acceptable field of inquiry until the Republicans started clutching their pearls and babbling hysterically about “cultural indoctrination.”

As for the argument that Republicans are the “real” patriots and the last true bulwark against the death of American democracy … you would think that after the January 6 riots, they would hang their heads in shame. But they have no shame.

Privately, most Republicans don’t believe the election was stolen. According to aides familiar with the matter, Trump himself admitted he lost in 2020. The rest is theater. Lucrative theater. Nothing they say can change three incontrovertible facts: 1) out of 62 lawsuits filed by Trump to challenge the 2020 election, 61 failed—and many of those cases were heard by Trump-appointed judges, 2) storming the nation’s capital, taking a hammer to the octogenarian husband of the Speaker of the House, and planning to kidnap Michigan governor Gretchen Whitmer are the opposite of democracy, 3) ask any Republican to show you proof of election fraud (articles from The Daily Caller don’t count), and all you’ll get for your trouble is sputtering indignation. “American media is corrupt,” they’ll say. But when you ask for proof of that corruption, they come up empty handed.

Of this you may be sure: If Democrats had staged a violent coup, Republicans would (rightly) be howling for their blood. Hell, I’d join them.

What happened on January 6th was inexcusable. Nine people died as a result of that shocking act of domestic terrorism, and as much as I thrill to the idea of revolution, history shows us time and again that most revolutions end bloody. Ours certainly have. But on this disgraceful episode in American history, Republicans who are not Liz Cheney and Adam Kinzinger tell us so much with their deafening silence.

So, if the Republican cri du coeur isn’t actually the economy, the armed insurrection, or the fact that Trump lost the 2020 election, what is it? What keeps these legions of aggrieved white voters in his thrall? It’s not his choice in ties. It’s the fact that Trump makes it abundantly clear where his sympathies lie, which is with white people.

“The Blacks,” Trump used to say on the campaign trail. “The African Americans.” These terms were pure dog whistle—Trump’s way of chumming the waters for his rabid followers. Trump and the Republican Party see Blacks monolithically: they all vote the same, think the same, suffer the same economic hardships, and hale from the same violent “shithole” countries and neighborhoods. Teargassing Black Lives Matter protesters so he could do a photo op wasn’t the least of Trump’s sins. He openly pandered to white supremacists. In fact, white supremacists were the “patriots” who stormed the Capitol for him on January 6. You know, to “save democracy.”

None of this would have surprised Ida B. Wells (July 16, 1862 – March 25, 1931), a remarkable African American civil rights advocate, journalist, and feminist you’ve probably never heard of. The way we teach American history is white-centric, phallocentric, and culturally tone deaf. The suppression of critical race theory isn’t new, you see. We’ve been doing this to a greater or lesser degree for a while.

Wells led an anti-lynching crusade in the United States in the 1890s. She was one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and had an outsized role in fighting for women’s suffrage. It is safe to say that without Ida B. Wells, Black feminism wouldn’t be the organized and powerful voting bloc it is today—a voting bloc that played a major role in ousting Trump from the White House.

She was born into slavery in Holly Springs, Mississippi in 1862, the eldest of eight children. Her father, James, was biracial. His own father, a white man, impregnated an enslaved Black woman. Wells’ mother, Lizzie, also enslaved, had been sold away from her family as a child. Despite repeated attempts, Lizzie was never able to locate her parents or any of her ten siblings after the Civil War.

Wells attended Rust College (now Shaw College, a private historically Black institution) until the loss of both parents and an infant brother forced her to drop out when she was sixteen. Wells was away visiting her grandmother when the yellow fever epidemic of 1878 fatally struck her family. In order to take care of her siblings, she convinced a local school administrator that she was eighteen and then worked as a teacher in order to care for her siblings.

Four years later, Wells and her brothers and sisters moved to Memphis, Tennessee, to live with their aunt. There, she was able to continue her education at Fisk University in nearby Nashville. But on May 4, 1884, while on a train going from Memphis to Nashville, Wells experienced firsthand the brutality of racism. The train conductor ordered Wells to relinquish her seat in the first-class ladies’ car and move to the smoking car, which Wells refused to do. The conductor and two others physically dragged her off the train.

Tellingly, the previous year, the United States Supreme Court had ruled against the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which banned racial discrimination in public accommodations. #BecauseAmerica.

Wells wrote about her experience in The Living Way, a Black church weekly. Then she hired an attorney to sue the railroad and won. A local circuit court awarded her $500, a handsome sum at the time. The railroad company appealed the decision, of course. In a ruling that surprised no one, the Tennessee Supreme Court reversed the lower court’s decision. Wells was even obliged to pay court costs.

The miscarriage of justice didn’t end there. In 1891, Wells was dismissed from her teaching post by the Memphis Board of Education because of her articles criticizing the subhuman conditions in Black segregated schools. The Board’s decision left her devastated, but Wells was never one to wallow in self-pity. Using a pen name, she doubled down on her criticism of Jim Crow policies, starting The Free Speech and Headlight in 1889, a Black-owned newspaper co-owned by the Reverend Taylor Nightingale.

Then came the People’s Grocery lynchings.

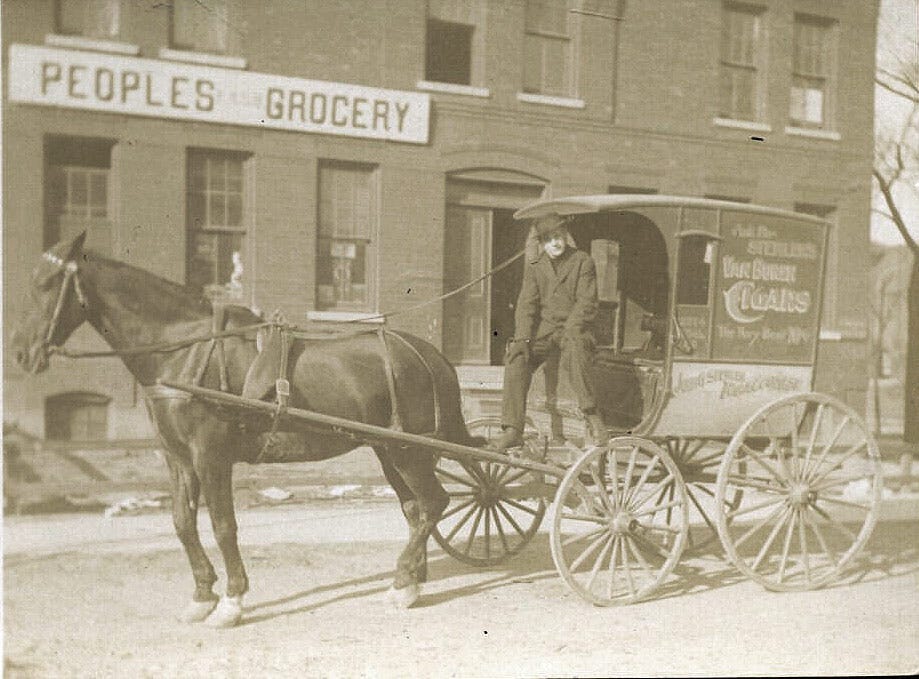

On March 9, 1892, in Memphis, a Black grocery owner named Thomas Moss and two of his employees were lynched by a white mob while in policy custody. There’d been an altercation between a Black child and a white one over a game of marbles. Moss rushed out of the store to stop the fight from escalating when the white boy’s father began beating the Black child. Within minutes, other people in the neighborhood came running in a “racially charged mob.”

The following day, a white grocer across the street who bitterly resented the success of Black-owned People’s Grocery, returned with a Shelby County Sheriff's Deputy and six others, determined to arrest Moss and his two associates. They were met by a hail of bullets from the People’s Grocery. The Shelby County Sheriff Deputy was wounded, as well as a civilian. Hundreds of white men were deputized on the spot to quell an “armed rebellion” staged by “dangerous Negroes” in People’s Grocery.

Moss and his associates were arrested. While the men were in custody, 75 masked intruders took them from their jail cells to a rail yard and then shot them dead. Moss reportedly said to the mob: “Tell my people to go west. There is no justice here.”

His real crime was the success of People’s Grocery. Previously, Barrett, the white grocer, had enjoyed the patronage of the entire neighborhood. He sold bootleg whiskey and oversaw the operation of a “low-dive gambling den.” Moss’s store was cutting into his bottom line. Ida B. Wells, risking her own life, reported on that and other lynchings, including one in Tunica, Mississippi, when the father of a young white woman had implored a lynch mob to kill the Black man his daughter was consensually sleeping with.

Wells’ articles incensed Memphis’s white population. A mob ransacked the Free Speech office, destroying the entire building and all of Wells’ printing equipment. Fortunately, Wells had been vacationing in Manhattan. The decision saved her life. She never returned to Memphis, and eventually, creditors seized her office and sold off all its assets. A “committee” rousted Reverend Nightingale, assaulted him, and forced him at gunpoint to sign a letter renouncing Wells’ editorials.

Wells never restricted herself to fighting for just one cause. She was an inspiring suffragist, particularly for Black women. On January 30, 1913 Wells founded the Alpha Suffrage Club in Chicago, which mobilized women in the city to elect candidates who would best serve the Black community. As president of the club, Wells was invited to march in the 1913 Suffrage Parade in Washington, D.C. Organizers, in particular a white suffragist named Alice Paul, asked women of color to march at the back of the parade.

Wells refused.

“When I was asked to come down here [to Washington, D.C.,] I was asked to march with the other women of our state, and I intend to do so or not take part in the parade at all,” she said.

Not all of the white Illinois suffragists agreed with the decision to exclude Wells. Virginia Brooks and Belle Squire spoke up and said that they would march by her side. Wells waited with the other spectators as the parade began, and then linked arms with Virginia Brooks and Belle Squire as a member of the Illinois delegation. Ida B. Wells may have found herself excluded from the march, but in a very important way, ended up leading it. Work done by Wells and the Alpha Suffrage Club played a crucial role in the victory of women’s suffrage with the passage of the Illinois Equal Suffrage Act in 1913.

By her fearless reporting on the horrors of lynching, Ida B. Wells left behind a legacy of social and political activism. In 2020, she was posthumously awarded a Pulitzer Prize “for her outstanding and courageous reporting on the horrific and vicious violence against African Americans during the era of lynching.” That’s because Wells is a hero. She was the 19th century Rosa Parks, a woman whose courage and determination continue to inspire us a century later.

I want you to remember Ida B. Wells as you watch the election returns tonight. Consider what she sacrificed to advance the cause of Black freedom and women’s emancipation. Then ask yourself if waiting in line to vote is really that big a deal.

Wells was willing to lay it all on the line to create a better world.

Are you?

Copyright © 2022 Stacey Eskelin

You know I love it when you share your thoughts with me. Feel free to chime in below.

I actually have heard of Wells, and while I've not read any of her work, while I was still on Twitter I was privileged to follow a woman who was (presumably still is) a leading scholar on Wells life and work.

I've been thinking much of this day about a certain class of lefties who refuse to vote because "both parties are the same." Basically a group of cry babies with the emotional and cognitive development of a four year old, throwing a tantrum because the world didn't give them everything they wanted, exactly the way they wanted it, the instant they wanted it. Where would we be now if people like Wells, or King after her, thought that way?

Things can go to shit very fast, but they only get better incrementally.

Somehow, saying that the group of neo-Fascists who want to realize Gilead in America are the same as those who argue for fully personal autonomy of women, human rights for gay and trans, and secure voting rights for all, are "the same" rings a tad hollow to me.

Wonderful article. I'd never heard of her.