A Hidden Life: Director Terrence Malick's Conversations with God

Even as a non-believer, I was deeply moved by this beautiful, elegiac film.

I’d like to start by confessing that I’m often wrong.

I’m especially wrong about what constitutes a good movie.

Everyone loved Sean Baker’s Florida Project. I hated it. No one liked or even watched Romanian New Wave masterwork Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn. I loved it. So, if you’d like to use my movie reviews as a negative frame of reference (“Stacey raved about that one. I’d better not watch it.”), I completely understand.

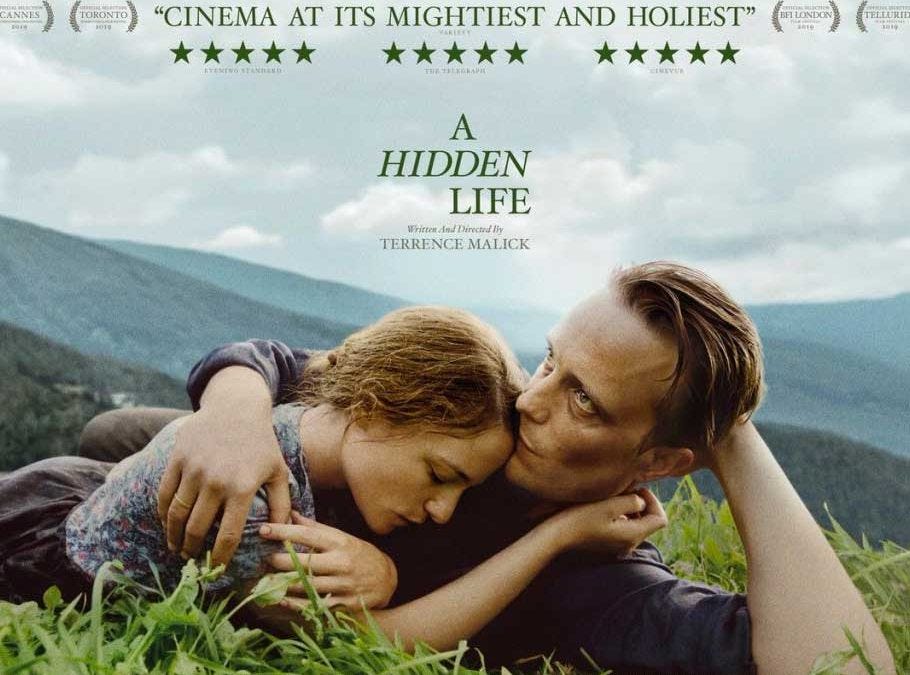

I offer this confession to you as a caveat emptor—even an apology—for my endorsement of Terrence Malick’s three-hour epic, A Hidden Life. The movie came out in 2019/2020, but with all we’ve been through, I figured you might have missed it the first time around, which is why I’d like to help you remedy an oversight.

Despite the setting (Hitler’s Austria), this is not a Holocaust film. It isn’t about star-crossed lovers, although that thread is woven into the narrative. It isn’t solely about religion, although a kind of spiritual exaltation soars through every frame, echoed by the obvious metaphor of “God’s cathedral”, a breathtaking backdrop of alpine beauty that Malick lingers on in nearly all scenes. The question he asks is a simple one: amid such staggering beauty, how can one not feel religious ecstasy?

Ultimately, however, this is a film about free will. And Malick refuses to provide us with easy answers.

The story begins in 1939 in Radegund, Austria, a mountain village that looks as though it’s perched at the top of the world. Fani (Valerie Pachner) and Franz (August Diehl) Jägerstätter and their three young daughters farm the land there. Despite the obvious hardship of struggling through hip-high snow, tending livestock, and scything stubborn crops, there is a dreaminess to these scenes, even as they remind us life is exhausting for those whose waking hours are devoted to the production of food.

“How simple life was then,” Fani says in voiceover. “It seemed no trouble could reach our valley … We lived above the clouds.”

Then, as Fani stands in blissful ignorance of what hell on earth is about to be unleashed, a German Messerschmitt drones overhead. Watching her try to puzzle out what it means makes your heart sink.

Hitler is introduced obliquely, in shadowy newsreel footage. Here, he dances on an alpine terrace to the silent refrain of a polka; there, his mistress Eva Braun drifts listlessly about in her dirndl. Here, an adorable child prinks in a wispy dress; there, SS officers look authoritative and official. A feeling of revulsion shudders delicately through the system as we behold the “innocent pleasures” of the most dangerous psychopath on earth. We know exactly what’s coming for the Jägerstätters.

Not unlike Paul Scofield’s Sir Thomas More in A Man for All Seasons, Franz finds himself unable to swear an oath of loyalty to his Führer. His refusal sets in motion everything that comes after, forcing us to decide whether Franz is being selfish, dogmatic, and inflexible, or whether he actually has a choice in the matter. This is signature Malick, by the way, a man who traffics in abstractions like faith, free will, and the kinds of sacrifices real love requires from all of us, in the end.

In A Hidden Life, we look for answers, but there are no answers; only an array of possible outcomes. We look for choices, but there are no choices, and I suspect that’s the point. With August Diehl’s Franz, it isn’t mere faith that prevents him from doing the one thing that will save his life and spare his family needless suffering. He never hesitates or second guesses himself because he already knows what we slowly glean over the course of the movie: there are some men who are incapable of dissembling in order to survive.

But are they heroes? Is there any heroism to be found in leaving your family to fend for itself?

The circumstances demand that you consider one of the most compelling questions of our age, especially with the advent of Covid-19: to whom does your life belong? That question is asked (and answered) by whether a person is willing to wear a simple mask. If you believe that your life belongs to you and that no one can tell you what to wear or how to behave, then the answer to that question is easy. Your life belongs to you. But for people who wear masks because they see the merit in protecting others from a deadly infectious disease, the answer is more complicated. For them, their lives belong to them, yes, but also to others.

But is Franz truly exercising free will by making a decision—or is there a certain amount of predestination in all this? That’s what Malick is asking us to consider. If the choices are swearing fealty to a psychopath or dying a violent and unnecessary death, most people are going to take the path of least resistance, which is swearing fealty. But is that free will? I do not believe that Malick’s Franz has a choice or free will. “Don’t they know evil when they see it?” he asks in a voice choked with horror.

Even if they do, few have the courage to stand up to it.

There is a moment in the movie when an artist hired to restore the village church reflects on his work. “I paint the tombs of the prophets,” he says. “I help people look up from those pews and dream. They look up and imagine that if they lived back in Christ’s time, they would have never done what the others did ….

”Christ’s life is a demand. We don’t want to be reminded of it, so we don’t have to see what happens to the truth. A darker time is coming when men will be more clever. They won’t fight the truth. They’ll just ignore it.”

Much of A Hidden Life is told in voiceover, which itself has a God-like omniscience that I find to be a particularly effective storytelling tool. It puts distance between the present and the past. The implication is that this breathtakingly beautiful moment is already over, which automatically jerks the heart strings.

But you might struggle to buy into a movie whose sole purpose is to move you. While I feel that the tears are earned, you may have a different opinion. Malick is a wayward director. More than just about anyone in Hollywood, he subscribes to the belief that the most beautiful tree in the forest must sometimes be sacrificed in order to save the forest. Just ask Christopher Plummer, who swore to never work with him again after a particularly compelling scene of his (in another movie) wound up on the cutting room floor.

You might also object to Malick’s decision to tell the story in English, but in his defense, let me say that reading subtitles would have detracted greatly from the point he is trying to make with the scenery.

This work of true beauty asks many questions, but of one thing it is sure:

Love suffers long and is kind. It is not proud. Love bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, and endures all things. Love never fails. And now these three remain: faith, hope, and love.

But the greatest of these is love.

What are your thoughts on Malick’s work or the work of writer/directors whose attempts to explain the ineffable succeeded or fall short? Be sure to leave your comments below.

Copyright © 2022 Stacey Eskelin

IMDB fails to list "A Hidden Life," on Terrence Mallick's home page, but he is credited as director on the movie's page.

Anyway, I looked him up.

And the two films of his that I've actually seen ("Pocket Money" from 1972 and "The Thin Red Line" from 1998, both where he is listed as writer and only the latter as director) I absolutely despised. As watchable as Lee Marvin and Paul Newman are ("were," I suppose) this film lacked any kind of character development, and just had two guys wandering around and accomplishing nothing. Thanks; that was really enlightening, even at 13. Thin Red Line, on the other hand, is an exercise in stream-of-consciousness dada-ist incoherence. IF there was a main character, you had no idea who it was because, with the exception of a few "name" stars, they all looked alike. And the "name" stars did nothing other than stand around and bloviate at intolerable lengths (Sean Penn), or be aggressively stupid (Woody Harrelson) who then blew himself up on his own grenade because he was too stupid to throw it away.

The only other director who has annoyed me this completely is Ridley Scott. People slobber praises about Scott without relent, and yet (at least until recently) the man could not -- no, revise that: WOULD NOT -- tell a fucking story, because he was too busy showing off what a clever director he is. "Alien"? Fucking seal youselves into a protected compartment and then vent the ship into space and just kill the damned thing. "Blade Runner"? An absolute abomination of Dick's story in which Harrison Ford's character only stands out for his complete incompetence. "Gladiator"? With a post relay of horses, it was three weeks from Germany to Spain, but Hero does it in two days and a night. Yet somehow the kill message got there ahead of him, at which point he passes out, and his picked up by slavers who wag his comatose body all the way across the Mediterranean ('cause that's what slavers do), which is another 3 week trip, by the way. Some of Ridley's work has become less idiotic since his brother (and superior director) Tony died.

That all being said, I'm afraid I will be very hard pressed to ever invest time or money in another Mallick film. Maybe he's grown up, as RS has shown signs of doing. But I won't pay for the privilege of finding out.

On a different note, more thematically oriented on the film's own themes, I'd like to mention that atheists are perfectly capable of having "spiritual" moments without apologizing for them. The "G-word" has been so corrupted by public discourse that many an "ouchie atheist" believes they must abandon -- indeed, aggressively excise -- any such thoughts or experiences from their lives. It is a rather sad position (I would argue) that is closer in logical structure to fundamentalism than it is to the supposedly scientific spirit such atheists claim they embody.

One way of looking at fundamentalism of any stripe, is that it is a technique employed to resolutely eliminate any last shred or scintilla of genuinely religious experience from religion. (John Dewey, in his lovely "A Common Faith," builds everything around the difference between the "religious" (the "spiritual") and "religion" (textual orthodoxy.)) I mean, think about it: people only appeal to dogmatic textual absolutism (fundamentalism) to hide themselves from any genuinely spiritual experience. The latter requires persons to open themselves up; the former demands they shut themselves down completely.

Most people who have genuinely sought the religious have, in the past, sought it in religion. There is no reason for this, as we've been (re)discovering these last 100+ years.

For the record, I certainly have no religion, and I do not count myself a religious person. I've had a few spiritual moments in my life, but I do not count them as defining.

That was a hell of an essay, Stacey. I will definitely seek out that film.